美国最高法院

| 美国最高法院 | |

|---|---|

| Supreme Court of the United States | |

| |

| 设立 | 1789年 |

| 所在地 | 华盛顿哥伦比亚特区 |

| 所在国 | |

| 经纬度 | 38°53′26.55″N 77°00′15.64″W / 38.8907083°N 77.0043444°W |

| 法官选任方式 | 美国总统提名并经参议院多数通过任命 |

| 设立法源 | 美国宪法 |

| 法官任期 | 终身制 |

| 法官人数 | 9 |

| 网址 | www |

| 首席大法官 | |

| 现任 | 约翰·格洛佛·罗伯茨 |

| 首长上任时间 | 2005年9月29日 |

|

| 美国政府与政治 系列条目 |

美国最高法院(英语:Supreme Court of the United States),一般是指美国联邦最高法院,是美国最高级别的联邦法院,为美国三权继总统、国会后最为重要的一环。根据1789年《美国宪法第三条》的规定,最高法院对所有联邦法院、州法院和涉及联邦法律问题的诉讼案件具有最终(并且在很大程度上是有斟酌决定权的)上诉管辖权,以及对小范围案件具有初审管辖权。在美国的法律制度中,最高法院通常是包括《美国宪法》在内的联邦法律的最终解释者,但仅在具有管辖权的案件范围内;例如最高法院并不享有判定政治问题的权力,关于政治问题的执法机关是行政机关,而不是司法部门。

最高法院通常由一位首席大法官和八位大法官组成。法官均由美国总统提名,在美国参议院投票通过后方可任命。一旦获参议院确认任命,法官享有终身任期,他们就无需再服从其原先的政党、总统、参议院的意志来审判。法官保留他们的职位直到去世、辞职、退休或弹劾(不过至今未出现法官被罢免的情况)。[1]在现代话语中,法官通常分为倾向保守派、温和派或自由派的法律哲学和司法解释。每位法官都有一票投票权,值得注意的是,虽然近期有很多案件得到全票通过,但最受人瞩目的裁定不过一票之差(五比四),因为这些判决透露了法官的政治思想信仰及背后的哲学或政治类比。最高法院的大法官在华盛顿哥伦比亚特区美国最高法院大楼办公。

最高法院有时会俗称为SCOTUS(美国最高法院的首字母缩写),类似于POTUS(美国总统)这样的首字母缩略词。[2]

2023年11月13日,美国最高法院发布道德准则,该守则适用于所有最高法院法官。[3][4][5]

历史

[编辑]

根据《美国宪法》,最高法院于1789年批准成立。最高法院的权力在《美国宪法》第三条中有详细规定。最高法院是唯一根据《美国宪法》专门设立的法院,而其他法院则由国会设立。国会可把最高法院法官头衔称呼作“大法官”(Justice),与下级法院法官(Judge)作区别。[6]

最高法院于1790年2月2日首次召开会议,[7]并在会议上确定了六位法官职位中的五位法官人选。据历史学家弗格斯·博尔德维奇,在最高法院的第一次会议上:“最高法院首次会议在布朗街皇家交易大楼举行,该大楼距离联邦大厅只有几步之遥。这个象征性的时刻孕育了共和国的承诺以及见证了这个新国家机构的诞生,其未来的权力诚然只存在于一些远见卓识的美国人的想象中。首席大法官杰伊和三名大法官,来自马萨诸塞州的威廉·库欣宾夕法尼亚州的詹姆斯·威尔逊和弗吉尼亚州的小约翰·布莱尔头戴假发,身着官服威严地坐在一大批观众面前并等待着有些事情发生。什么事情都没有发生,因为无案可审。闲着一周,他们休庭到九月,然后各回各家了”[8]。

第六名成员詹姆斯·伊雷德尔直到1790年5月12日才得以确认。由于全席法院只有6名大法官,因此所有判决都是经过多数也就是三分之二的表决(四对二的投票表决)而做出决定。[9]然而,从1789年法定的四名法官人数开始,国会一直准许法院少于正式成员做出表决。[10]

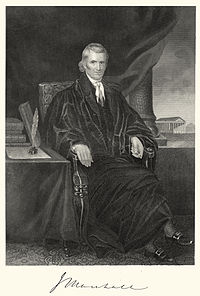

成立之初到马歇尔

[编辑]在首席法官杰伊、拉特利奇和埃尔斯沃斯时期,上审讯案件不多;第一个判决的是维斯特诉巴恩斯案(1791)涉及的程序性问题案件。[11]最高法院没有自己的办公大楼且声望不大,这样的境况并未因审讯那个时代最受瞩目的案件而得到改善,[12]却由奇泽姆诉佐治亚州案(1793)在两年内通过的《第十一条修正案》得以推翻。[13]

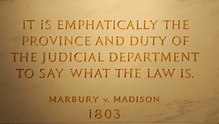

在马歇尔法院(1801-35)期间,最高法院的权力和声望得到大大提升。[14]在马歇尔的领导下,最高法院确立了对国会行为进行司法审查的权力,[15] 包括将最高法院定为《宪法》最终的解释者(马伯里诉麦迪逊案),[16][17]并作出了若干重要的宪法判决以赋予联邦政府和各个州之间权力平衡的形式和实质。(特别是,马丁诉亨特之承租人案、麦卡洛克诉马里兰州案和吉本斯诉奥格登案)。[18][19][20][21]

马歇尔法庭也终结了仿照英国法院,每个法官在每起案件中依次撰写司法意见的做法,[22]而是由一人撰写多数意见书。[23]在马歇尔任期内,1804至1805年期间,塞缪尔·蔡斯大法官的弹劾和无罪判决有助于巩固了司法独立的原则,尽管此事脱离了最高法院的控制。[24][25]

从托尼到塔夫脱

[编辑]坦尼法庭(1836-1864)作出了若干重要判决,例如谢尔顿诉西尔案,认为尽管国会不能限制最高法院的听审,但可限制联邦下级法院的管辖权,以防止他们涉及某些范畴的审理案件。[26]然而这主要是斯科特诉桑福德案的判决引起内战而为人铭记。[27][28]在重建时期,蔡斯、韦特和富勒法院(1864-1910)将新的内战修正案解释为《宪法》,[21]并制定了实质性正当程序的理论(劳克莱与纽约州案;[29]阿黛尔诉合众国案)。[30]

在怀特和塔夫脱首席大法官(1910-1930)的领导下,最高法院认为《第十四修正案》保证了《人权法案》对包括州政府在内的各级地方政府都有效(基特洛诉纽约州案),[31]其中涉及新的反托拉斯法(标准石油公司诉合众国案),维护军事征兵的合宪性(选择性法律草案案件),[32]并将实质性正当程序原则上升至至其最高点(艾德金斯诉儿童医院案)。[33]

新政时期

[编辑]在休斯、斯通和文森首席大法官(1930 - 1953年)法院期间,最高法院在1935年获得了独立的办公大楼,[34]并变更了对《宪法》的解释,对联邦政府的权力进行了更宽广的解读,以促进富兰克林·罗斯福总统的新政的推行(最突出的是西岸宾馆诉帕里什案、维卡德诉费尔本案、合众国诉达比案和美利坚合众国诉巴特勒案)。[35][36][37]在第二次世界大战期间,最高法院继续支持政府公权力,认定日公民的拘留(是松诉合众国案)和强制宣誓(迈纳斯维尔学区诉戈比蒂斯案)合宪。然而,戈比蒂斯案很快被推翻(西弗吉尼亚教育局诉巴尼特案),钢铁公司占领案制约了最高法院亲政府的趋势。

沃伦和伯格

[编辑]以第14任美国首席大法官厄尔·沃伦为首的沃伦法院(1953-1969年)是美国历史上最为自由派的最高法院,期间大幅扩大了宪法公民自由的力量。[38]认为公立学校的种族隔离违反了平等保障(布朗诉托皮卡教育局案,博林诉夏普案和格林诉新肯特县县教育董事会案),[39]传统的划分选区违反了选举权(雷纳德诉西蒙斯案)。此外,还承认了隐私权(格里斯沃尔德诉康涅狄格州案),[40]限制了宗教在公立学校(最著名的是恩格尔诉瓦伊塔尔案和阿宾顿学区诉维权案)中的作用,[41][42]保证了《人权法案》对包括州政府在内的各级地方政府都有效---最突出的是马普诉俄亥俄州案(证据排除法则)和吉迪恩诉温赖特案(指定律师的权利)[43][44]---并要求被疑人有权知道自己的所有权(米兰达诉亚利桑那州)。[45]与此同时,法院则要求公众人物在指控媒体报道涉嫌诽谤时必须遵循的原则(纽约时报诉沙利文案),为政府提供获得反垄断胜利的完整运作。[46]

伯格法院(1969-1986)标志着保守派的崛起。[47]虽然其间还扩大了格里斯沃尔德的隐私权,以七比二通过堕胎合法化(罗诉韦德案),[48]但在肯定性行动上(加利福尼亚大学诉巴克案)和竞选财政法规(巴克利诉法奥里奥案)产生了严重分歧,[49][50]以及关于死刑制度的犹豫不决,首先裁定大多数申请是有缺陷的程序(弗曼诉佐治亚州案),[51]然后裁定死刑本身并不违宪(格雷格诉乔治案)。[51][52][53]

伦奎斯特和罗伯茨

[编辑]伦奎斯特法院(1986 - 2005)使最高法院正式由保守派控制,复兴联邦制的司法解释而著称,[54]强调宪法授予国会权力的限制(合众国诉洛佩兹案)和对这些权力限制的效力(塞米诺尔部落诉佛罗里达州案、伯尔尼市诉弗洛雷斯案)。[55][56][57][58][59]法院也判定仅招生单性别学员的学院违反平等保护(合众国诉弗吉尼亚州案),反鸡奸法是违反实质性正当程序的法律(劳伦斯诉得克萨斯州案),[60]以及分项否决权(克林顿诉纽约市案) ,但维持了学券制(泽尔曼诉西蒙.哈里斯案),并重申了罗伊对堕胎法的限制(计划生育组织诉凯西案)。[61]在2000年的总统选举中,最高法院对布什诉戈尔案中决定重新点算选票结束了选举,这是有争议的。[62][63]

罗伯茨法院(2005年至今)被一些人认为是比伦奎斯特法院更为倾向保守派。[64][65]其中一些主要判决涉及联邦法律优先适用(惠氏公司诉莱文案),民事诉讼程序,堕胎(冈萨雷斯诉卡哈特案),[66]气候变化(麻塞诸塞州控告美国环保署),同性婚姻(合众国诉温莎案和奥贝格费尔诉霍奇斯案)和《权利法案》,特别是联合公民诉联邦选举委员会案(第一修正案),[67]海勒案和麦当劳案(第二修正案)[68]和巴泽诉里斯案(第八修正案)。[69][70]

组成

[编辑]规模

[编辑]《美国宪法》第三条并没有制定大法官人数。1789年的《司法法案》要求任命6名大法官,随着国界的增加,国会增加了大法官人数以应对日益增长的司法诉讼:于1807年增加到7人,在1837年增加到9人,而在1863年增加到了10人。

1866年,根据首席大法官查斯的要求,国会通过了一项法案规定接下来的三名退休大法官的空缺不会填补,使大法官人数维持7人。因此,在1866年,大法官的总人数降到了9人,在1867年又降到了8人。然而在1869年,《巡回法官法》重新将大法官人数规定至9人,[71]这一数字也一直保持至今。

富兰克林·罗斯福总统在1937年试图扩大最高法院的规模。他建议总统可以提名另一名法官取代任何超过70岁6个月但还没有退休的联邦法官,并可以借此把最高法院的大法官人数增加到15名。这项提议表面上是为了减轻老年法官的负担,但所有人都知道,真正的理由是是为了向法院填塞支持罗斯福新政的法官。[72]这个常被称为“最高法院填塞”的计划没有在国会通过。[73]然而,威利斯·范·德文特大法官退休,大法官席位由参议员雨果·布莱克替换后,最高法院的平衡开始转移。到1941年底,罗斯福已经任命了七名大法官,并将哈伦·菲斯克·斯通升任为首席大法官。[74]

提名和确认

[编辑]

前排左起:大法官索尼娅·索托马约尔、大法官克拉伦斯·托马斯、首席大法官约翰·罗伯茨、大法官塞缪尔·阿利托, 大法官艾蕾娜·卡根,后排左起:大法官艾米·康尼·巴雷特、大法官尼尔·戈萨奇、大法官布雷特·卡瓦诺、大法官凯坦吉·布朗·杰克森

美国《宪法》规定,美国总统“提名,经参议院同意任命最高法院法官。”[75]虽然大法官的判定最终可能与总统的期望相违背,大多数提名总统候选人都会宣扬其意识形态观点。美国《宪法》未对联邦最高法院大法官任职资格作任何规定,总统可提名任何人担任这一职务,但须经参议院批准。

近代,参议院批准的过程引起了新闻界和宣传组的高度重视,游说参议员批准或拒绝提名候选人取决于其档案是否符合党派观点。美国参议院司法委员会就提名是否应以正、负或中立报告提交参议院全体议员提出听证和投票。委员会亲自面试候选人是较新的做法。在1925年,哈伦·菲斯克·斯通是第一位提名候选人委员会的听证会上出现的提名候选人。斯通试图消除关于他与华尔街关联的担忧,而近代的质疑做法在1955年出现始于约翰·马歇尔·哈兰二世。[76]一旦委员会将提名法案提交全院会议并附审查报告,参议院全体议员将进行审查。反对相对来说是不常见的;参议院已明确地反对了十二名最高法院的提名人,最近一次的反对提名是在1987年的罗伯特·博克。

尽管参议院的明文规定并不一定认可在司法委员会中投反对票来阻止提名,但在2017年之前,一旦参议院全体议员的辩论开始,阻挠议事的议员将可能阻挠提名。林登·约翰逊总统提名担任大法官的亚伯拉罕·亚伯·方特斯于1968年接任厄尔·沃伦为首席大法官,这是阻挠最高法院提名的第一个成功案例。这包括了共和党和民主党参议员所关注的方特斯的伦理观。唐纳德德·特朗普总统提名尼尔·戈萨奇填补安东宁·斯卡利亚的空缺席位,这是第二个经阻挠成功提名的案例。然而,与福塔斯的阻挠者不同,只有民主党参议员投票反对戈萨奇的提名,因为他们对戈萨奇保守的司法哲学表示怀疑。此前共和党多数派曾反对接受奥巴马总统提名的梅域·加兰填补空缺。[77][78][79]这导致共和党多数派取消规定以消除对最高法院提名的阻挠。[80]

并非每个最高法院的被提名人都可获得参议院投票。总统可以在任命投票发生之前撤回提名,撤回通常是因为参议院明确反对提名人;最近撤回提名的是在2006年的哈里特·米尔斯。参议院也可能无法按提名行事,届时将在会议结束时终止。例如,德怀特·艾森豪威尔总统在1954年11月第一次提名约翰·马歇尔·哈兰二世时,没有参议员采取行动;艾森豪威尔总统在1955年1月重新提名哈兰,参议院在2个月后批准了其提名。最近,如前所述,参议院未对在2016年3月提名梅域·加兰的提名有任何动作;该提名于2017年1月份到期,而该空缺后来由特朗普总统任命的尼尔·戈萨奇填补。[81]

一旦参议院确认大法官提名,总统必须在新法官任职前签署一份带有司法部印章的委任状。[82]大法官的资历是基于任命日期而不是确认或宣誓日期。[83]

1981年以前,大法官的审批程序通常很快。从杜鲁门到尼克松政府,大法官的任命通常在一个月内得到批准。[84]然而,从里根政府到现在,这个过程需要更长的时间。一些人认为这是因为国会认为法官比过去更具政治色彩的作用。根据国会研究机构统计,自1975年以来提名至参议院投票的平均天数为67天(2.2个月),而其中值为71天(或2.3个月)。[85][86]

休会期间的任命

[编辑]当参议院休会时,总统可以临时任命填补空缺。休会期间的被任命者只有在下一届参议院会议结束(少于两年)前任职。参议院必须确认被提名人是否能够继续任职;在休会期间任命的两名首席大法官和十一名大法官中,只有首席大法官约翰·拉特利奇随后并未得到参议院的确认。[87]

自德怀特·艾森豪威尔后,再没有总统在参议院休会期间任命大法官。这种做法即使是在低级的联邦法庭也是非常罕见和具有争议的。[88]1960年,在艾森豪威尔作出三次这样的任命之后,参议院通过了“参议院意见”的决议,在休会期间的任命只能在“异常情况”下作出。[89]这些决议并没有法律约束力,而是表达了国会的意见以指导行政命令。[89][90]

2014年最高法院在国民劳工关系委员会诉诺埃尔坎宁案中限制总统休会期间任命(包括最高法院的任命)的权力,表示参议院自行决定参议院会议何时举行(或休会)。大法官布雷耶判决书指出:“我们认为,关于休会期间的任命,参议院可根据需要在自己的规则下举行会议,并保留参议院事务的能力。”[91]这项判决允许参议院通过预案会议来防止休会任命。[92]

任期

[编辑]《美国宪法》规定,所有大法官一经上任,“如行为端正”则可终身任职(除非是在参议院休会期间的任命)。“行为端正”一词意味着大法官除非被国会弹劾并被定罪、辞职或退休,就可以终身任职。[93]仅有一名大法官被众议院(塞缪尔·查斯,1804年3月)弹劾,但参议院于1805年3月判决他无罪。[94]在最近发生的现任大法官弹劾包括威廉·道格拉斯在1953年和1970年两次听证会审查; 亚伯拉罕·亚伯·方特斯在1969年5月辞职,1969年曾组织听证会,然而没有在众议院投票表决。没有制度解释可以换掉大法官,即使其由于疾病或伤害而永久丧失工作能力,都不能(或不愿意)辞职。[95]

因为大法官的任期是终身的,其空缺时间是不可预知的。有时,空缺很快出现,很多时候和政治形势有关。就像1960至70年代大法官更换频繁,刘易斯·鲍威尔和威廉·伦奎斯特提名填补雨果·布莱克和约翰·马歇尔·哈伦二世空缺,他们都在一个星期内退休或辞职。有时候,提名之间有很长一段时间,例如1994年斯蒂芬·布雷耶获得提名接任哈利·布莱克蒙,到约翰·罗伯茨于2005年的提名替补桑德拉·戴·奥康纳的席位相隔了11年(尽管罗伯茨的提名被撤回并在伦奎斯特去世后重新提名为首席大法官)。

尽管可变,除了四位总统以外,其他总统都能够至少任命一名大法官。威廉·亨利·哈里森上任后一个月去世,然而他的继任者约翰·泰勒在总统任期内任命了大法官。同样,扎卡里·泰勒上任十六个月后去世,但他的继任者米勒德·菲尔莫尔也在该任期结束之前提出了最高法院的提名。在亚伯拉罕·林肯遭到暗杀后成为总统的安德鲁·约翰逊由于最高法院席位的减少,而不能任命大法官。自富兰克林·罗斯福后,除吉米·卡特外,所有总统均有参与大法官的提名和任命。卡特是唯一一个在总统任期内没有机会任命大法官的。同理,詹姆斯·门罗总统,富兰克林·罗斯福总统和乔治·W·布什总统都没有机会在第一任期内任命大法官,但在第二任期期间任命了大法官。任职满一个任期的总统都至少有一次机会任命大法官。比尔·克林顿和贝拉克·奥巴马均在第一个任期内提名了两位大法官,其中奥巴马在2016年提名了第三名大法官,但受共和党阻拦而无法上任。而唐纳德·特朗普则在一个任期内任命三名大法官,仅次于乔治·华盛顿单个任期所任命大法官人数。

三位总统安德鲁·杰克逊,亚伯拉罕·林肯和富兰克林·罗斯福任命的大法官是全体任职合共超过100年的。[96]

成员

[编辑]当前成员

[编辑]以下是美国最高法院当前[update]的9名大法官,表中“确认票数”指参议院确认总统提名时的票数。在现任法官中,克拉伦斯·托马斯是任期最长的法官,截至2024年11月10日,其任期为12,072天(33年18天);最近加入法院的法官是凯坦吉·布朗·杰克森,其任期始于2022年6月30日。

| 大法官 / 出生日期和地点 |

任命总统 | 确认票数 | 年龄 | 开始日期 服务时间 |

学历 | 意识形态[97] | 最近履历 | 接替 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 开始 | 目前 | |||||||||

|

(首席大法官) 约翰·格洛佛·罗伯茨 1955年1月27日 布法罗 |

乔治·沃克·布什 | 78–22 | 50 | 69 | 2005年9月29日 19年42天 |

哈佛大学 (法律博士) | 保守派 | 美国哥伦比亚特区联邦巡回上诉法院法官 (2003–2005) | 伦奎斯特 |

|

克拉伦斯·托马斯 1948年6月23日 平波因特 |

乔治·赫伯特·沃克·布什 | 52–48 | 43 | 76 | 1991年10月23日 33年18天 |

耶鲁大学 (法律博士) | 保守派 | 美国哥伦比亚特区联邦巡回上诉法院法官 (1990–1991) | 马歇尔 |

|

塞缪尔·阿利托 1950年4月1日 特伦顿 |

乔治·沃克·布什 | 58–42 | 55 | 74 | 2006年1月31日 18年284天 |

耶鲁大学 (法律博士) | 保守派 | 美国联邦第三巡回上诉法院法官 (1990–2006) | 奥康纳 |

|

索尼娅·索托马约尔 1954年6月25日 纽约 |

贝拉克·奥巴马 | 68–31 | 55 | 70 | 2009年8月8日 15年94天 |

耶鲁大学 (法律博士) | 自由派 | 美国联邦第二巡回上诉法院法官 (1998–2009) | 苏特 |

|

艾蕾娜·卡根 1960年4月28日 纽约 |

贝拉克·奥巴马 | 63–37 | 50 | 64 | 2010年8月7日 14年95天 |

哈佛大学 (法律博士) | 自由派 | 美国副总检察长 (2009–2010) | 史蒂文斯 |

|

尼尔·戈萨奇 1967年8月29日 丹佛 |

唐纳德·特朗普 | 54–45 | 49 | 57 | 2017年4月10日 7年214天 |

哈佛大学 (法律博士) | 保守派 | 美国联邦第十巡回上诉法院法官 (2006–2017) | 斯卡利亚 |

|

布雷特·卡瓦诺 1965年2月12日 华盛顿哥伦比亚特区 |

唐纳德·特朗普 | 50-48 | 53 | 59 | 2018年10月6日 6年35天 |

耶鲁大学 (法律博士) | 保守派 | 美国哥伦比亚特区联邦巡回上诉法院法官 (2006–2018) | 肯尼迪 |

|

艾米·康尼·巴雷特 1972年1月28日 新奥尔良, 路易斯安那州 |

唐纳德·特朗普 | 52-48 | 48 | 52 | 2020年10月27日 4年14天 |

圣母大学 (法律博士) | 保守派 | 美国联邦第七巡回上诉法院法官 (2017–2020) | 金斯伯格 |

|

凯坦吉·布朗·杰克森 1970年9月14日 华盛顿哥伦比亚特区 |

乔·拜登 | 53–47 | 51 | 54 | 2022年6月30日 2年133天 |

哈佛大学 (法律博士) | 自由派 | 美国哥伦比亚特区联邦巡回上诉法院法官 (2021–2022) | 布雷耶 |

大法官统计

[编辑]最高法院目前有5名男性大法官和4名女性大法官。在九名大法官当中,有两名非裔美国人(托马斯大法官和杰克森大法官)和一名西班牙裔美国人(索托马约尔大法官)。有一名大法官的父母至少有一方是移民:阿利托大法官的父亲出生于意大利。[98][99]

至少六名大法官是罗马天主教徒,两名是犹太教;其中目前尚不清楚尼尔·戈萨奇是天主教徒还是美国圣公会教徒。[100]从历史上看,大多数大法官都是基督教新教徒,其中包括36名美国圣公会教徒,19名长老会教徒,10名自然神论者,5名卫理公会派教徒和3名浸信会教徒。[101][102]第一位天主教大法官是1836年任命的罗杰·B·坦尼,[103]第一位犹太大法官是1916年任命的路易斯·布兰迪斯。[104]近年来情况已经扭转。现时最高法院均由犹太人和天主教徒组成。

3名大法官来自纽约州,2名大法官来自华盛顿特区,新泽西州、佐治亚州、科罗拉多州和路易斯安那州各1名。8位大法官拥有常春藤联盟法学院的教育背景:尼尔·戈萨奇、凯坦吉·布朗·杰克森、艾蕾娜·卡根、约翰·罗伯茨来自哈佛;塞缪尔·阿利托、布雷特·卡瓦诺、索尼娅·索托马约尔和克拉伦斯·托马斯来自耶鲁。只有艾米·康尼·巴雷特在圣母大学获得了她的法律学位。。[105]

在最高法院的大部分历史里,每个大法官都具有欧洲血统(通常是西北欧),而且几乎是新教徒。多样性主要是在地理上的,代表了该国的所有地区,而不是宗教,种族或性别的多样性。[106]种族和性别的多样性在二十世纪末期开始不断增大。瑟古德·马歇尔于1967年成为第一个非裔美国人大法官。[104]桑德拉·戴·奥康纳于1981年成为第一位女性大法官。[104]非裔美国人克拉伦斯·托马斯于1991年继任了马歇尔的席位。[107]奥康纳之后,鲁思·巴德·金斯伯格于1993年成为了第二位女性大法官。[108]奥康纳退休后,接着索尼娅·索托马约,第一个拉丁裔女性大法官于2009年加入最高法院,[104]以及在2010年任命的艾蕾娜·卡根。[108]2022年6月30日,凯坦吉·布朗·杰克森成为最高法院首位非洲裔美国女性大法官。[109]

最高法院历史上有六名在外国出生的大法官:詹姆斯·威尔逊(1789-1798),出生于苏格兰的卡斯卡地区;詹姆斯·艾德尔(1790-1799),出生于英国雷威斯;刘易斯·威廉·帕特森(1793-1806),出生于爱尔兰安特里姆郡;大卫·布鲁尔(1889-1910),出生于奥斯曼帝国士麦那(今土耳其士麦那);乔治·萨瑟兰(1922-1939),出生于英国白金汉郡以及费利克斯·弗兰克福特(1939-1962),出生于奥匈帝国维也纳(现属于奥地利)。[104]

退休大法官

[编辑]目前美国联邦最高法院共有三位退休大法官:大卫·苏特、安东尼·肯尼迪和斯蒂芬·布雷耶。退休大法官不会再参与联邦最高法院的审判工作,但可能被临时指派到下级联邦法院办公,其中以美国联邦上诉法院为主。这类指派乃系基于下级法院院长请求,经退休法官同意后,由首席大法官指派。近几年来,奥康纳大法官便曾在数个联邦上诉法院中办事,另外,苏特大法官也经常在其担任大法官前任职的第一巡回上诉法院中参与审判。

| 大法官 出生日期和地点 |

任命总统 | 退休时总统 | 岁数 | 任期 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 开始 | 退休 | 目前 | 开始 | 结束 | 时长 | ||||

|

安东尼·肯尼迪 1936年7月23日 萨克拉门托 |

罗纳德·里根 | 唐纳德·特朗普 | 51 | 82 | 88 | 1988年2月18日 | 2018年7月31日 | 30年163天 |

|

戴维·苏特 1939年9月17日 梅尔罗斯 |

乔治·赫伯特·沃克·布什 | 贝拉克·奥巴马 | 51 | 69 | 85 | 1990年10月9日 | 2009年6月29日 | 18年263天 |

|

斯蒂芬·布雷耶 1938年8月15日 旧金山 |

比尔·克林顿 | 乔·拜登 | 55 | 83 | 86 | 1994年8月3日 | 2022年6月30日 | 30年99天 |

资历和座席

[编辑]法院的许多内部运作是由基于法官的资历进行的;不论其服务时间长短,美国首席大法官被认为资历最深的法官。而大法官乃是依据任命的次序论资排辈的。

在法庭会议期间,大法官根据资历排座,首席大法官坐在法庭中央,大法官则坐在候补席上。最资深的大法官坐在首席大法官右侧,而最资浅者坐在离大法官最远的左侧。

在大法官们的闭门会议上,目前的做法是由首席大法官首先发言,接着由最资浅者开始依序发表意见,资历最深的大法官最后发言。这些会议中最资浅的大法官在单独召开会议时可能需要做任何微不足道的任务,例如假如有人敲会议室的门,将由最资浅的大法官来应门,以及将最高法院的命令传达给最高法院的书记员。[114]大法官约瑟夫·斯多利任职资浅大法官最久,任期从1812年2月3日至1823年9月1日,共4,228天。紧随其后是大法官斯蒂芬·布雷耶,为4199天,1994年至在2006年1月31日。塞缪尔·阿利托也在同一天加入最高法院。[115]

薪资

[编辑]截至2021年,首席大法官的年薪为280,500 美元,其他大法官则为268,300美元。[116]根据美国《宪法》第三条第一节规定,禁止国会降低现任大法官的薪资。一旦大法官符合退休年龄和退休任职的规定,其可申请退休。大法官的退休金是基于联邦政府的雇员使用的相同公式计算的,但与其他联邦法院的法官一样,大法官退休金将不会低于退休时的薪资。

大法官的倾向

[编辑]虽然大法官是由总统提名的,但大法官也不代表或接受政党的官方认可,而立法和行政部门也普遍接受了这种做法。然而,大法官在法律和政治界被非正式地分为司法保守派、温和派或自由派。这种倾向通常是指法律前景而不是政治或立法方面。大法官的提名需由在立法机构的政治人士赞同,他们以投票通过或不赞成大法官的提名。

继凯坦吉·布朗·杰克森的任命确认后,最高法院由6名由共和党总统任命的大法官和3名由民主党总统任命的大法官组成。现在普遍接受的是,首席大法官罗伯茨和大法官托马斯、阿利托、戈萨奇、卡瓦诺、巴雷特(由共和党总统任命)组成了最高法院的保守派。大法官索托马约尔、卡根和杰克森(由民主党总统任命)组成了最高法院的自由派。根据戈萨奇在第10巡回上诉法院的记录看来,他是属于很保守派的大法官。[117]卡瓦诺在被任命为最高法院法官之前,被认为是华盛顿特区巡回法院中比较保守的法官之一。[118][119]同样的,巴雷特在第七巡回法院的简短记录也是保守的。[120]在金斯伯格大法官去世之前,首席大法官罗伯茨被认为是法院的中位数大法官(处于意识形态光谱的中间,有四位大法官比他更自由,四位大法官比他更保守),使他成为法院的意识形态中心。[121][122]

汤姆·戈德斯坦2010年在SCOTUS博客发表的一篇文章中提到,大众对最高法院是在意识形态方面进行大幅划分,每一方在每一轮都推动一个议程如漫画旨在“在很大程度上适应某些先入为主的偏见”。[123]他指出,在2009年的任期,近一半的案件是全体一致决定的,只有约20%由5票对4票决定的。只有十分之一的案件涉及狭义的自由派/保守派的划分(如果不包括索托马约尔的案件,则更少)。他还指出,几个案例反驳了最高法院的派别划分的普遍观念。[124]戈德斯坦进一步指出,大量的先前的刑事被告人撤回诉讼(通常是法官判定下级法院明显错误应用先例并在没有通报或论证的情况下扭转这种情况)就是表明,保守派的大法官没有积极的意识形态。同样地,戈德斯坦也表示,自由派的大法官更有可能作废国会的法令,显示出对政治进程的不尊重,并且不尊重先例,也缺乏优点:托马斯是最经常呼吁推翻先例的(即使长期以来)他曾经错误地做出判定,在2009年任期间,斯卡里亚和托马斯是投最多反对票,判定国会立法无效。

根据SCOTUS博客的统计数字,2000年至2011年的12个任期中,平均19个主要问题(22%)的判定是由5-4票决定,平均70%的分歧意见由最高法院以传统意识形态派别判定的(约占所发表陈述的15%)。在那段时期里,保守派集团在62%以意识形态为主的判决的时候占多数,占所有5-4票判决的44%。[125]

2010年10月任期,最高法院判决了86起案件,其中包括75件已签署的多数意见和5份判决撤销(最高法院驳回下级法院,不提出异议,不对案件发表陈述)。[126][127]4起案例以未签名陈述判定,2起案例需最高法院做出确认,还有2起案例的案件作出判定,另有2起案件驳回不予受理。由于大法官卡根曾任美国副总检察长,她回避了26起案件。在80起案例中,有38例(约为48%,自2005年10月任期以来最高的比例)是全体一致(9-0或8-0)的判定,16例是以5-4票判定的(约20%,而在2009年10月任期是18%,在2008年10月任期为29%)。[128]然而,在16例的5-4票判决中的14例中,最高法院以传统的思想路线划分(属于自由派的是金斯伯格、布雷耶、索托马约尔和卡根),保守派包括罗伯茨、斯卡里亚、托马斯、阿利托以及肯尼迪大法官的“关键票”)。占这16例中的87%,是过去10年来最高的比例。在肯尼迪大法官加入后,保守派集团在5-4票判决中占63%。[126][129][130][131][132]

2011年10月任期,法院判定了75起案件。其中,33例(44%)全体一致判定,15例(20%,与前一任期相同的比例)由5-4票判定。后15年,最高法院根据意识形态线划分了10次,肯尼迪大法官与保守派的大法官(罗伯茨、斯卡里亚、托马斯和阿利托)站队5次,与自由派的大法官(金斯伯格、布雷耶、索托马约尔和卡根)站队5次。[125][133][134]

2012年10月,最高法院判决了78起案件。其中五起是以未签名陈述判决的。78项判决中有38项(占判定的49%)是全体一致的判决,而24项判定是完全一致的(即所有参与的大法官有同一个陈述)。自2002年10月的任期以来,这是最高法院十年来全体一致判决的最大比例(51%的判决是全体一致作出的)。最高法院在23个案件中分立为5-4判决(占总数的29%);其中有16个案件是以传统意识形态划分,首席大法官法官罗伯茨、大法官斯卡里亚、托马斯和阿利托是站在同一个阵营,金斯伯格、布雷耶、索托马约尔以及卡根则站在另一个阵营,而肯尼迪大法官则具有决定权。在这16起案件中,肯尼迪法官大法官有10例是站在保守派阵营,有6例是站在自由派阵营。其中在3起案件的判决中,大法官阵营划分非常有趣,首席大法官罗伯茨加入肯尼迪、托马斯、布雷耶和阿利托大法官为多数派,而大法官斯卡里亚、金斯伯格、索托马约尔和卡根则为少数派。大法官之间意见一致最多的是金斯伯格和卡根,在他们投票的75个案件中,72件意见一致;意见最不一致的是大法官金金斯伯格和阿利托,他们投票的77件案件中,45件意见一致。根据他作为最高法院“关键票”的立场,肯尼迪大法官在24起案例中的20起及任期内78起案例中的71起站在5-4票判定的多数方。[135][136]

设施

[编辑]

最高法院于首次会议于1790年2月1日在纽约市皇家交易所大楼举行。当费城成为首都时,最高法院在1791年至1800年在旧市政厅办公前,曾在独立厅举行了短暂的会议。政府搬到华盛顿特区后,最高法院在美国国会大厦的多个地方办公,直到1935年,最高法院终于有了专属的办公大楼。四层楼高的最高法院大楼是由卡斯·吉尔伯特(Cass Gilbert)设计,其古典风格配上大理石外墙与国会大厦和国会图书馆周围的建筑物相当。该大楼包括法庭,大法官大厅,拥有广泛法律书籍的图书馆,各种会议场所和配套设施如健身房。最高法院的建筑物是属于国会大厦建筑的范围,但其警察部队独立于国会警察局。[137]

位于One First Street NE和马里兰大街,[138][139]即美国国会大厦的街对面,美国最高法院大楼周一至周五上午9时至下午4时30分向公众开放,周末和假期不开放。[138] 参观者不得自己参观法庭。建筑内有一个自助餐厅,一个礼品店,展品以及时长半小时的宣传片。[137]最高法院休庭期间的上午9时30分至下午3时30分,每小时都举行有关法庭的讲座,无需预约。[137]当法院在十月至四月每隔两周的周一、二、三的早上(有时候是下午)举行庭审期间,公众可以旁听口头辩论,至十二月至二月暂停。旁听坐席先到先得,一场公开的庭审大概有250个旁听席位。[140]开放旁听席位的数量随着不同案件的情况而不同;对于重要的案件,一些访客会在前一天到达并等待一整夜。从五月中旬至六月底,最高法院从上午十时开始发布判决或司法意见,这些15至30分钟的庭审活动也以类似的方式向公众开放。[137]最高法院警察可以回答公众的问题。[138]

管辖权

[编辑]

国会根据联邦宪法第三条授权控制最高法院的上诉管辖权。对于两个州或以上的案件,最高法院具有初审和专属管辖权,[141]但他们可能拒绝开审这类案件。[142]同时,最高法院还拥有初始非专属管辖权,以听审“大使,其他部长,领事馆或外国副领事组织的一切诉讼,美国与其他国之间的一切争议以及所有诉讼或一国对另一国公民或外侨的诉讼。”[143]

在1906年的合众国诉希普案,最高法院维护其初审管辖权起诉藐视法庭的个人。[144]由此所产生的诉讼仍然是最高法院历史上唯一的蔑视诉讼且进行刑事审判的事件。[145][146]蔑视诉讼起因于在大法官约翰·马歇尔·哈兰允许埃德·约翰逊的律师提出上诉后, 约翰逊晚上在田纳西州查特怒加市被以私刑处死。一个私行死刑的暴民在一名地方警长的协助下,将约翰逊被从他的监牢中移走,并将其挂在大桥上。之后,一名副警长用别针在约翰逊的身上钉了一张纸条:“致哈兰大法官,现在来找你的老黑吧。”[145]当地警长,约翰·希普(John Shipp)以最高法院的干预作为私刑的理由。最高法院任命其副书记员为特别主事人主持在查特努加的审判,且在华盛顿最高法院大法官前进行了结辩陈词。9名犯人被判犯藐视罪,3名犯人判处3至90日的监禁,其余6人判处60天的监禁。 [145][146][147]

然而,在所有其他情况下,最高法院都有只有上诉管辖权,包括签发职务执行以及禁止下级法院的令状。考虑到基于其初审管辖权的案件不多,于是几乎所有案件都在最高法院上诉。实际上,仅有的涉及初审管辖权且最高法院法官听审的案件,是州与州之间的争执。[来源请求]

最高法院的上诉管辖权包括来自联邦上诉法院的上诉(通过调取案卷的令状,调取案卷的令状前的认证和刑事责任问题),[148]美国武装力量法院(通过调取案卷的令状),[149]波多黎各最高法院(通过调取案卷的令状) ,[150]维尔京群岛最高法院(通过调取案卷的令状),[151]哥伦比亚特区上诉法院(通过调取案卷的令状),[152]以及“对州最高法院作出的最终判决或命令做出判定”(通过调取案卷的令状) 。[152]在最后一类案件中,如果一个州的最高法院拒绝听审上诉或缺乏听审上诉的管辖权,可向最高法院提起上诉。例如,佛罗里达地区上诉法院拒绝作出判决,如果(a)佛罗里达州最高法院拒绝调取案卷的令状,如佛罗里达州之星诉B. J. F.案,或(b)地方上诉法院发布了一项引用法院判词的决定,只是肯定了下级法院的判定,而不讨论案件所涉及的实体问题,那么可向最高法院提出上诉。这是因为佛罗里达州最高法院缺乏听审类似判定的上诉管辖权。[153]基于1789年的《司法法案》创立的最高法院的权力可接受考虑州法院而不仅仅是联邦法院的上诉。通过对且在马丁诉亨特之承租人案 (1816)和科恩斯诉弗吉尼亚州(1821)中判决中看出这是最高法院的早期历史始终坚持的。尽管有几种允许所谓“程序与附随审查 ”的州案件,但最高法院是唯一一个对州法院判决的直接上诉具有管辖权的联邦法院。必须指出的是,这种“附带审查”通常仅适用于死囚,而不适用于常规司法系统。[来源请求]

由于美国《宪法》第三条规定,联邦法院只能受理“案件”或“争议”,最高法院不能像一些州最高法院那样不就相关案件作出判决或不出具意见。例如,在Defunis诉 Odegaard 416 U.S. 312(1974)案中,416 U.S. 312 (1974)法院驳回了诉讼,质疑法学院平权政策的合宪性,因为原告学生开始诉讼后已从该学院毕业,最高法院的判定是无法补救原告所受损害。然而,最高法院认定在某些情况下,听审似乎没有意义的案件是有益的。如果一个问题是“可以重新回避审查”的话,即使原告在最高法院并不一定会得到有利结果,最高法院也会处理该问题。在罗伊诉韦德案(1973)以及其他堕胎案件中,410 U.S. 113 (1973)最高法院也会处理怀孕妇女所提出的堕胎要求,即使后来不怀孕了。因为通过下级法院向最高法院提起上诉的案件的处理时间通常比正常妊娠期的时间要长。另一个诉由消失的例外是自愿停止非法行为,最高法院考虑再次发生这种行为的可能性以及原告人是否需要救济。[154]

大法官作为巡回法官

[编辑]美国共分为13个巡回上诉法院,其中每一个上诉法院均由最高法院分配一个“巡回大法官”。虽然这个概念在共和国的历史上一直存在,但其意义却随时间推移而变化。

根据1789年的《司法法案》,每位大法官都必须在审判区管辖范围内或在指定巡回法庭内作巡回审判,并与当地法官一起审理案件。这做法由于巡回审判路途遥远和困难而遇到许多大法官的反对。此外,大法官在巡回法庭可能判定与最高法院利益冲突的案件。巡回审判于1891年废除。

如今,在审判区管辖范围内的巡回大法官负责处理某些类型的申请,根据法院的规定,这些申请可以单独由一名大法官进行解决。其中包括紧急中止(包括在死刑案件中执行死刑的中止)的申请以及在审判区管辖范围内的案件引起的“全令状法案”的禁令以及日常要求如请求延长时间。过去巡回法官有时还在刑事案件中作出保释,人身保护令,以及上诉许可调案令的申请。一般而言,大法官通过简单地批示“批准”或“拒绝”或指示进入某一标准程序来解决这类申请。然而,如果大法官愿意的话,可以选择在这种情况下发表意见(称为庭内意见)。

巡回大法官可作为该巡回上诉法院的法官,但在过去的一百年里几乎不曾发生。在上诉法院,巡回大法官的资历比巡回法庭的审判长高。

首席大法官传统上会分配到哥伦比亚特区巡回法院,第四巡回法院(包括马里兰州和弗吉尼亚州,即哥伦比亚特区邻近的州)以及联邦巡回法院。每个大法官会分配到一或两个巡回法院。

截至2022年9月28日,大法官巡回法院分派如下:[155]

| 巡回上诉法院 | 巡回大法官 |

|---|---|

| 哥伦比亚特区巡回上诉法院 | 首席大法官罗伯茨 |

| 第一巡回上诉法院 | 大法官杰克森 |

| 第二巡回上诉法院 | 大法官索托马约尔 |

| 第三巡回上诉法院 | 大法官阿利托 |

| 第四巡回上诉法院 | 首席大法官罗伯茨 |

| 第五巡回上诉法院 | 大法官阿利托 |

| 第六巡回上诉法院 | 大法官卡瓦诺 |

| 第七巡回上诉法院 | 大法官巴雷特 |

| 第八巡回上诉法院 | 大法官卡瓦诺 |

| 第九巡回上诉法院 | 大法官卡根 |

| 第十巡回上诉法院 | 大法官戈萨奇 |

| 第十一巡回上诉法院 | 大法官托马斯 |

| 联邦巡回区上诉法院 | 首席大法官罗伯茨 |

现任法官中有五名被分配到他们以前担任巡回法官的巡回法院:罗伯茨首席大法官(哥伦比亚特区巡回上诉法院)、索托马约尔大法官(第二巡回上诉法院)、阿利托大法官(第三巡回上诉法院)、巴雷特大法官( 第七巡回上诉法院)、戈萨奇大法官(第十巡回上诉法院)。

程序

[编辑]最高法院的工作庭期从每年10月的第一个星期一开始并持续到次年6月或7月初。每个庭期由大约两周的交替时期组成,称为“开庭”和“休庭”。大法官们在开庭期间听审案件并作出判决;他们在休庭期间讨论案件并撰写判决陈述。

案例选择

[编辑]几乎所有案件都以请愿书方式提交给最高法院,通常被称为“上诉书”。最高法院可以根据任何民事或刑事案件的任何一方的呈请给予的复审令,审查联邦上诉法院的任何案件。[156]如果这些判决涉及联邦法律或宪法法律的问题,法院可能只会审查“州最高法院作出的最终判决”。[157]向最高法院上诉的一方是上诉人,非提请人是被告。无论哪一方在初审法院发起诉讼,所有案件名称都是上诉人诉被告人。例如,亚利桑那州诉埃里内斯·米兰达案是以州的名义对个人提起刑事起诉。如果被告已定罪,那么在向最高法院上诉时,将确认其定罪。而当米兰达以其向提出案件上诉申请时,该案的名称将变为米兰达诉亚利桑那州。

有些情况是属于最高法院的初审管辖权,比如当两个州之间有争议时或者当美国联邦政府与一个州之间出现争端时。在这种情况下,案件可直接向最高法院提起诉讼。这种情况的例子包括合众国诉得克萨斯州案,该案旨在确定是否一宗地属于美国或得克萨斯州。弗吉尼亚州诉田纳西州案,是否两州错误划分的边界可由最高法院进行更改以及州与州之间的正确边界设定是否需要国会批准。虽然自1794年以来没有发生类似乔治亚诉布列斯福德案的案件,[158]各方法律行动中,最高法院具有初审管辖权并可以要求陪审团判定事实争议。[159]另外两个初审管辖权案件涉及殖民时代通航水域之下的边界和权利的新泽西州诉特拉华州案,诉以及河岸州上游水域的水权的堪萨斯州诉科罗拉多州案。

投票决定是否批准调审令的庭审会议为会商。会商是在9个大法官内部的秘密会议;公众和大法官的书记员将排除在外。如果有4名大法官投票通过上诉,案件将进入简报通报阶段;反之,案件结束。除死刑案件及其他最高法院要求被告通报的案件外,被告不需要提交对请求调审令的答复。

最高法院只基于“令人信服的理由”而批出请求调审令的,在“最高法院10点规则”中阐明原因。包括:

- 解决在解释联邦法律或联邦宪法条款方面的冲突

- 纠正严重偏离公认的司法程序的惯例

- 解决联邦法律的一个重要问题,或明确审查下级法院的裁决,该裁决与法院先前的裁决直接冲突。

当不同的联邦巡回上诉法院对同一法律或宪法规定的解释发生冲突,律师称之为情况“巡回法院分裂”。如果法庭投票拒绝请求调审令,如绝大多数上诉一样,通常是不出具意见的。驳回上诉并不是判决案件的案情,而下级法院的判决将是该案件的最终判决。

为了处理法院每年收到的大量上诉(法院每年收到的7,000多个上诉中,仅要求100份或以下案件的简报并进行庭审口头辩论),最高法院采用了称为“调审令池“的内部案件管理工具。目前,除了大法官阿利托和戈萨奇,其他大法官都参加复审小组。[160][161][162] [163]

口头辩论

[编辑]当法院提出请求调审令时,该案子设定为口头辩论。双方将就案件的案情简要介绍案件的不同之处,他们可为批准或拒绝请求调审令而提出不同的理由。经双方同意或最高法院批准,“法庭之友”也可以提交辩护状 。最高法院从10月至4月每月举行2周的口头辩论。每一方都有三十分钟的时间提出其论点(法院可能会选择给予更多的时间,但很罕见),[164]在陈述时间里,大法官可能会打断律师并提问。上诉人首次发表陈述时,可以在被告陈述结束之后,预留一些时间来驳回被告的论据。如果另一方同意,法律之友可代表一方作出口头辩论。最高法院建议律师假设大法官熟悉并阅读了案件的简报。

最高法院律师协会

[编辑]为了向法庭提出抗辩,律师必须首先被最高法院律师协会承认。每年约有4000名律师加入该协会。最高法院律师协会预计有23万名会员。实际上,诉状仅限于数百名律师。其余律师加入协会需缴纳一次性费用200美元,每年赚取大约75万美元。律师可以以个人或团体的名义承认。团体承认是在最高法院现任法官面前进行的,其中最高法院首席法官批准接纳新律师的动议。[165]律师通常申请协会是为了将承认证书放在办公室或简历上显示。如果他们希望参加口头辩论,他们也可以获得更好的坐席。[166]最高法院律师协会的成员也可以进入最高法院图书馆馆藏。[167]

判决

[编辑]口头辩论结束后,提交案件判决。案件的判决由法官的多数票决定。最高法院的做法是在该期限结束时在特定期限内对有争议的所有案件作出判决。然而,在这个期限内,最高法院无义务在口头辩论之后的任何规定时间内作出判决。在口头辩论结束后,法官退到另一次初步投票的会议,占多数资历最高的大法官将最高法院陈述的初步草案分派给同一阵营的大法官。最高法院在特定情况宣布判决最高法院的陈述草案以及大法官们的任何同意或异议陈述。[168]由于在美国最高法院大楼的法庭内禁止使用录音设备,所以是通过纸质副本将判决传递给媒体,这被称为是“实习生的营运”。[169][170]

最高法院有可能因为大法官空缺,导致案件票数打平。如果发生这种情况,那么下级法院的判决会被承认(affirm),但不会变成有约束力的判例。听审案件,必须有至少六名大法官在场。[171]如果人数不足可以听取案情,大多数合格的大法官认为一个案子不能在下一个任期内听审和裁定,那么下级法院的判决就如同最高法院的打平一样得到确认。对于通过美国地方法院直接上诉向最高法院提起的案件,最高法院首席大法官可将有关案件发回到有关的美国上诉法院作出最后裁定。[172]这在美国历史上只发生过一次,就是合众国诉美国铝公司案(1945年)。[173]

发布陈述

[编辑]最高法院的陈述分三个阶段发布。首先,最高法院的网站和其他网站发布一个判决简述。然后,法院命令的几个陈述和清单都以平装书的形式结合在一起,称为美国报告的初步出版材料,官方系列书将呈现最高法院最终版的陈述。在发行初步出版材料大约一年后,将发布《美国最高法院判例报告》最终合订本。《美国报告》的每一卷都有编号,以便用户可以引用这套报告 - 或由另一个商业合法发布商发布但包含平行引用的竞争版本,以帮助那些想通过阅读诉状和其他简报快速轻松地查找案例的人。

截至2019年1月[update],出版有:

- 《美国报告》最终合订本569卷,涵盖截至2013年6月13日全部案例(部分2012年10月任期)。[174][175]

- 21卷的陈述以判决简述的形式(卷565-585,2011-2017年任期,每期三卷,每卷两部分)发布,外加卷568第一部分(2018年任期)。[176]

截至2012年3月,《美国报告》共出版了30161份最高法院的陈述,涵盖了从1790年2月至2012年3月的裁定。[来源请求] 这一数字并不能反映最高法院审理案件的数量, 因为多个案件可以通过一个陈述处理(例如,社区学校学生家长诉西雅图学区案与梅雷迪思诉杰斐逊县教育委员会案以相同的陈述作出裁定;根据类似的逻辑,米兰达诉亚利桑那州案实际上不仅裁定了米兰达案,还裁定了其他三个案件:威哥尼拉诉纽约州案,韦斯特欧沃诉合众国案和加州诉斯特沃特案)。一个更不寻常的例子是“电话案例”,其中包含一整套相互联系的陈述,在《美国报告》中占据了整个第126卷。

陈述也通过两名非正式的平行汇编发表:由西方(现为汤森路透一部分)出版的《最高法院判例汇编》和由LexisNexis公司出版的《美国最高法院报告,律师版》简称“律师版”。在法庭文件,法律期刊和其他法律媒体中,案件引文一般源于三本汇编的一处;例如联合公民诉联邦选举委员会案的引文以联合公民诉联邦选举委员会案,585 U.S. 50,130 S. Ct. 876, 175 L. Ed. 2d 753 (2010)呈现。其中,"S. Ct."代表《最高法院判例汇编 》,“L. Ed”代表律师版。[177][178]

引用发表陈述

[编辑]律师使用缩写格式,即以“vol U.S. page, pin (year)”引用案件。其中vol为卷号,page为陈述开始的页码,year为该案裁定的年份,pin用于“精确定位”到意见中的特定页码。例如,罗伊诉韦德案的引文是410 U.S. 113 (1973),这表明该案是在1973年判决的,并出现在《美国报告》第410卷第113页中。对于尚未在初步印刷材料中发表的陈述或法定,卷和页码可以替换为“___”。

制度性权力和制约因素

[编辑]在起草和批准《宪法》的辩论中,联邦法院制度和司法当局对《宪法》的解释几乎没有引起关注。事实上司法审查的权力在这上面是没有提到的。在接下来的几年中,司法审查的权力是否是宪法起草者意图的问题,很快就因为缺乏对这一问题的证据而受到阻挠。[179]然而,司法机构推翻法律和行政行为的权力是非法或违宪的,这是一个既定的先例。许多开国元勋接受司法审查的概念;亚历山大·汉密尔顿在联邦党第78号写道:“法官必须将《宪法》视为一项基本法。因此他们需要确定其中的意义;以及任何立法机构特定诉讼法的意义。如果两者之间发生不可调和的差异,(前者)应该有优先的义务和有效性的优先权;或者换句话说,宪法应该优于立法机构和法令。”

最高法院在马布里诉麦迪逊法案(1803)中确定了宣布违反宪法的法律权力,完善了美国制衡制度。在解释司法审查权力时,首席大法官约翰·马歇尔表示,解释法律的权力是法院的特定职权,司法部门有义务说明法律是什么。他的论点并不是说法院有特权洞察宪法的要求,而且《宪法》所规定的司法机构以及其他政府部门的义务是阅读并遵守《宪法》的规定。[180]

自共和国成立以来,司法审查的做法与平等主义、自治、自决、信仰自由的民主理想处于紧张关系。一方面是将联邦司法机构,特别是最高法院视为“最分离,最少检查所有政府部门”的人。[181]事实上,联邦法官和最高法院大法官不必以其任期内的“良好行为”期间而被推选,而且他们的薪酬在担任职务期间是不可能“减少”的(第三条第一节)。虽然有弹劾的程序,但只有一个大法官曾经被弹劾,至今没有最高法院的大法官被免职。另一方面则将司法机构视为最不危险的分支机构,几乎没有能力抵制其他政府部门的劝诫。[180]据指出,最高法院不能直接执行判决;相反,其依赖于尊重宪法和法律来维持其判决。 著名的例子是1832年出现的不服从,当时在伍斯特诉乔治亚案,佐治亚州忽视了最高法院裁定。安德鲁·杰克逊总统与佐治亚州法院一致表示:“约翰·马歇尔大法官已经作出判决,现在让他执行吧!”[182]然而,这个所谓的引用是有争议的。南方的一些州政府也在1954年布朗诉教育委员会案的判决后,抵制了公立学校的废除种族隔离。最近很多人担心,尼克松总统拒绝遵守最高法院在美国诉尼克松(1974年)的命令交出水门事件的录音带。然而,尼克松总统最终还是遵守了最高法院的判决。

宪法修正案可以(并已)推翻最高法院的判定,已有5个案例:

- 奇泽姆诉格鲁吉亚案(1793年) - 被第十一修正案(1795)推翻

- 斯科特诉桑福德案(1857) - 被第十三修正案(1865)和第十四修正案(1868)推翻

- 波洛克诉农民贷款和信托公司(1895年)- 被第十六修正案(1913年)推翻

- 迈纳诉Happersett案(1875) - 被第十九修正案(1920)推翻

- 俄勒冈诉米切尔案(1970) - 被第二十六修正案(1971年)推翻

当最高法院对涉及法律而不是宪法的事宜进行判决时,简单的立法行动可以扭转判定(例如,2009年国会通过了莉莉·莱德贝特公平薪酬法,取代了2007年莱德贝特诉固特异轮胎和橡胶公司案中的限制)。此外,最高法院不能免于政治和制度上的考虑:低级联邦法院和州法院有时会违反教义创新,执法官员也是如此。[183]

另外,其他两个分支机构可以通过其他机制来限制最高法院。国会可以增加大法官的数目,使总统有权通过任命来影响未来的判定(如上述的罗斯福最高法院填塞计划)。国会可以通过限制最高法院和其他联邦法院对某些议题和案件的管辖权的立法:这是第三条第2节中的建议,如果上诉管辖权“具有此类例外情况,国会可以根据这些法律执行。“最高法院在偏袒一方的麦卡德尔(1869)“重建”案件中认定国会判决,但其拒绝了国会在美国诉克莱因案(1871年)中判定特定案件的权力。

另一方面,最高法院通过司法审查的权力,界定了联邦政府立法机关和执行部门之间的权力和分离的范围和性质; 如在合众国诉柯蒂斯 - 赖特出口公司案(1936),在戴姆斯与摩尔诉里根案(1981)中,特别是高华德诉卡特案(1979)(其中有效地给予总统权力终止未经国会或参议院同意的情况下批准的条约)。 法院的判决也可以对执行权力的范围施加限制,如汉弗莱执行机构诉美国(1935年),钢铁缉获案(1952年)和合众国诉尼克松案(1974年)。

律政书记

[编辑]每个最高法院的大法官配有几个律政书记协助审查和研究复审令的请愿书,并准备法官备忘录和起草陈述等。大法官允许有4个书记员。首席大法官允许有5个书记员,但首席大法官伦奎斯特每年仅聘请3个书记员以及首席大法官罗伯茨通常只聘请4个。[184]一般来说,律政书记的任期为一到两年。

大法官霍勒斯·格雷于1882年聘请了第一位律政书记。[184][185]小奥利弗·温德尔·霍姆斯和路易斯·布兰迪斯是最先聘请法学院应届毕业生而不是秘书兼速记员为书记员。[186]大多数法律政书记都是刚毕业的法学院毕业生。

大法官威廉·道格拉斯于1944年聘请了第一位女书记员露西尔·洛门。[184]大法官费利克斯·弗兰克福特于1948年聘请了第一个非裔美国人威廉·科尔曼。聘请的律政书记绝大多数从精英学校获得法律学位,特别是哈佛大学、耶鲁大学、芝加哥大学、哥伦比亚大学、斯坦福大学法律学位,这十分不均衡。从1882年到1940年,62%的律政书记是哈佛大学法学院的毕业生。[184]最高法院所选择的律政书记通常是其法学院班级的精英,且经常是法学评论编辑或模拟法庭董事会的一员。到了70年代中期,在联邦上诉法院担任过法官书记员成为了担任最高法院大法官书记员的先决条件。[187]

8名最高法院大法官曾为其他大法官担任书记员:拜伦·怀特曾担任弗雷德·文森的书记员,约翰·保罗·史蒂文斯曾担任威利·拉特里奇的书记员,威廉·伦奎斯特曾担任罗伯特·H·杰克逊的书记员,斯蒂芬·布雷耶曾担任阿瑟·戈德堡的书记员,约翰·罗伯茨曾担任伦奎斯特的书记员,埃琳娜·卡根曾担任瑟古德·马歇尔的书记员,尼尔·戈萨奇曾担任拜伦·怀特和安东尼·肯尼迪的书记员,以及布雷特·卡瓦诺曾担任肯尼迪的书记员。戈萨奇和卡瓦诺大法官曾在肯尼迪手下同时任职。戈萨奇是第一位与自己曾担任过书记员的大法官同时在任的大法官,从2017年4月开始,直到2018年肯尼迪退休。随着卡瓦诺大法官提名的确认,最高法院的多数成员首次由前最高法院书记员组成(罗伯茨、布雷耶、卡根、戈萨奇和卡瓦诺)。

几位现任最高法院大法官也曾在联邦上诉法院担任书记员:约翰·罗伯茨曾担任美国第二巡回上诉法院法官亨利·弗兰德利的书记员,大法官塞缪尔·阿利托任美国第三巡回上诉法院法官伦纳德·I·加思的书记员,埃琳娜·卡根曾担任美国哥伦比亚特区巡回上诉法院法官艾伯纳·J· 米克瓦的书记员以及尼尔·戈萨奇曾担任美国哥伦比亚特区上诉法院法官大卫·B·森特尔法官的书记员。

法院政治化

[编辑]最高法院大法官聘请的书记员通常在起草陈述时留下相当大的回旋余地。根据范德比尔特大学法学院法律评论2009年发表的一项研究,“最高法院书记员似乎是从20世纪40年代到80年代一直是一个无党派机构”。[188][189]前联邦上诉法院法官J. Michael Luttig说:“随着法律越来越趋近于政治,政治关系自然而且可预见地成为通过法院压制的不同政治议程的代理人”。[188]剑桥大学历史教授戴维·杰罗夫(David J. Garrow)表示,法院已经开始反映出政府政治部门的影子。加罗教授称“我们的书记员工作队伍的组成越来越像众议院的组成”。“各方都提出只有意识形态的纯粹主义者。”[188]

根据范德比尔特法律评论研究,这种政治化的聘请趋势加深了最高法院是“反思意识形态论据而不是以法治为由的法律制度的法律机构”的印象。[188]《纽约时报》和哥伦比亚广播公司新闻”2012年6月的调查显示,只有44%的美国人赞成最高法院所做的工作。四分之三的受访者表示,法官的判定有时受到其政治或个人看法的影响。[190]

批判

[编辑]法院一直是在一系列问题上的批判对象。其中:

司法能动主义

[编辑]最高法院被批评为不在宪法范围内行使司法能动主义,而非解释法律和行使司法限制。司法能动主义的诉求并不局限于任何特定的意识形态。[191]经常被引用的保守司法行为主义的例子是1905年洛赫纳诉纽约州案的判决,许多著名的思想家包括罗伯特·博克,安东宁·斯卡利亚大法官和首席大法官约翰·罗伯茨都对该判决进行批评。[191][192]经常被引用的自由主义司法行为主义的例子是罗诉韦德案(1973),将堕胎合法化,其部分原因是基于“第十四修正案”所表达的“隐私权”,一些批评者认为这是迂回的推理。[191]法学家、[193][194]大法官[195]和总统候选人[196]都批判了罗伊的判决。布朗诉教育委员会案的判决受到保守派人士如帕特里克·布坎南[197]和前总统竞选人贝利·高华德的批判。[198]最近,联合公民诉联邦选举委员会案的判定被批评为改变长期以来第一修正案对公司不适用的观点。[199]林肯总统警告说,关于斯科特诉桑福德案的判决,如果政府政策变得“不可逆转且被最高法院的判决所限定...人民将不再是自己的统治者了”。[200]前任大法官瑟古德·马歇尔用这些话来证明司法能动主义:“你做你认为是对的事,让法律在后面追”。[201]在不同的历史时期,法院的倾向不同。[202][203]双方的批评家都抱怨说,持激进观点的法官以自己的观点代替了宪法。[204][205][206]评论家还包括Andrew Napolitano,[207]Phyllis Schlafly,[208]Mark R. Levin,[209]Mark I. Sutherland[210]和James MacGregor Burns等作家。[211][212]过去来自两党的总统都对司法能动主义发起攻击,其中包括富兰克林·罗斯福、理查德·尼克松、罗纳德·里根总统。[213][214]最高法院提名人罗伯特·博克(Robert Bork)说:“法官所做的就是一场政变,一场缓慢移动,踩着高跷地,但仍然是政变。”[215]参议员阿尔·弗兰肯(Al Franken)指出,当政界人士谈论司法能动主义时,他们对一名能动主义法官的定义是一个不同于他们投票想要的人。[216]一位法学教授在一篇于1978年发表的文章中称,最高法院在某些方面“是立法机构”。[217]

未能保护个人权利

[编辑]因为没有保护个人权利,法庭的判决受到批判:斯科特案(1857)判定维持奴隶制;[218]普莱西诉弗格森案(1896)根据“隔离但平等”的原则维持种族隔离;[219]凯洛诉新伦敦市案(2005年)被包括新泽西州州长乔恩·科兹宁在内的杰出政治家批评为破坏财产权。[220][221]有报道称一些批评家认为,保守派占多数的2009年大法官席位“变得与印第安纳州的选民相抵触”,这些法案倾向于“剥夺大量没有驾照公民的投票权,特别是穷人和少数民族选民。”[222]艾尔·弗兰肯参议员批评最高法院“侵蚀个人权利”。[216]不过,也有人认为,法院过于保护个人权利,特别是被指控犯有或被拘留的人的权利。例如,首席大法官沃伦·伯格是一个直言不讳的批评者,斯卡利亚大法官批评最高法院在布迈丁诉布什案的判定中是否过分保护关塔那摩被拘留者的权利,理由是人身保护令应受主权领土的限制。[223]

最高法院权力太大

[编辑]这种批评与司法能动主义的抱怨有关。[224]乔治·威尔(George Will)写道:最高法院在美国国家管理中扮演着越来越重要的角色。对介入2009年关于汽车制造商克莱斯勒公司的破产程序的批判。[225]一位记者写道:“露丝·巴德·金斯伯格大法官干预克莱斯勒破产案”并公开了“进一步司法审查的可能性”。但从总体上认为这种干预是适当运用最高法院的权力以对行政部门进行审查。[225]沃伦·伯格在成为首席大法官之前曾认为,由于最高法院具有这种“不可见的权力”,所以其很可能“自我沉迷”,不可能“进行冷静的分析”。[226]拉里·萨巴托(Larry Sabato)写道:“联邦法院,特别是最高法院已经过度授权”。[227]

法院难以制约行政权力

[编辑]英国宪法学者亚当·汤姆金斯(Adam Tomkins)认为,美国的法庭(特别是最高法院)制度的行为和立法机构有缺陷。他认为,由于法院须多年的等待才能通过这个制度,才能严格限制其他两个分支。[228][229]相比之下,德国联邦宪法法院可以经请求可直接宣布违反宪法的法律。

联邦与国家权力

[编辑]美国历史上曾有过有关于联邦和国家权力界限的辩论。詹姆斯·麦迪逊[230]和亚历山大·汉密尔顿[231]等筹划者在《联邦党人文集》中提出,他们当时提出的《宪法》并不会侵犯州政府的权力,[232][233][234][235]但另一些人认为,联邦政府的扩充的权力与制宪者的愿望是一致的。[236]美国《宪法》第十修正案明确授予《宪法》未授予的美国权力分别向国家或人民保留。由于最高法院给予联邦政府太多的权力干涉国家权力机关而受到批评其中一个批判如下,最高法院允许联邦政府滥用商业条款,维护与州际商业无关的规定和立法,但这是以规范州际商业的幌子颁布的;并且因为涉嫌干涉州际商业,致使国家立法无效。例如,第五巡回上诉法院采用“商业条款”来维护“《濒危物种法》,从而保护得克萨斯州奥斯汀附近的六种特有的昆虫种类。尽管昆虫没有商业价值,也没有跨越州边界;最高法院于2005年通过这一判决。[237]首席大法官约翰·马歇尔认为,国会完全可以行使州际商业的权力到最大限度。除了《宪法》规定之外,不承认任何限制。[238]大法官阿利托表示,商务条款下的国会权力是“相当广泛的”。[239]现代理论家罗伯特·B·德里克建议现在应继续讨论《商业条款》。[238]国家权力倡导者如宪法学者凯文·古兹曼也批判了法院,称其滥用了第十四修正案破坏国家的权威。布兰迪斯法官辩称允许各州在没有联邦干预的情况下运作,这表明国家应该是民主的实验室。[240]一位评论家写道:“最高法院判决违宪的绝大多数案件都是涉及州法律而不是联邦法律。”[241]不过,其他人认为《第十四修正案》是将“保护这些权利和保障提升到国家层面”的积极力量。[242]

秘密诉讼

[编辑]因其陪审团判决不向大众公开,最高法院受到批评。[243] 根据杰弗里·托宾(Jeffrey Toobin)的评论《9位大法官,最高法院的秘密世界》:记者难以将最高法院内部运作报道出来,正如一个封闭的“卡特尔”,仅能通过不包括内部运作的公共事件和出版物进行自我揭露。[244]评论写道:“很少有记者能够深入挖掘法院事务。最高法院内部运作良好。但唯一受伤的是美国人民,他们对于最有权威的9名大法官知之甚少。”[244]拉里·萨巴托抱怨法院与外界隔绝。[227]2010年的菲利·迪金森大学调查发现,61%的美国选民同意举行电视法庭听证会有利于民主”,50%的选民表示如果机会的话他们会收看电视转播的最高法院法庭诉讼。[245][246]近年来,许多大法官的身影都出现在电视和书籍上,并向记者发表了公开声明。[247][248]在2009年的C-SPAN采访中,记者约翰·比斯丘皮克(今日美国)和莱尔·丹尼斯顿 (SCOTUS博客)认为,最高法院是一个“非常开放”的机构,只有大法官的私人会议不向公众开放。[247]2010年10月,最高法院开始在其网站上发布其星期五进行的口头辩论的记录和文本。

司法干涉政治争端

[编辑]最高法院的某些判决被批评为将最高法院置于政治舞台之上,并决定其他两个政府分支的职权。布什诉戈尔案的判定是最高法院在2000年美国总统选举结果的实际干预,并决定最终的选举结果,大法官中5比4的判决,五名保守派大法官支持禁止佛罗里达州的重新计票,“选择”乔治·W·布什而不是普选票较多的阿尔·戈尔成为第43任美国总统,这个案件的判决受到特别是民主党的广泛批评。[244][249][250][251][252][253]另一个案例是最高法院关于分配和重划选区的判决:在贝克诉卡尔案中,最高法院裁定可以对分配问题作出判定;法兰克福大法官反驳最高法院的判决涉嫌所谓的政治问题。[254]很多牵涉政治争端的司法判决通常展现5比4,判决亦反映大法官的政治意识形态。

没有选择足够的案例进行审查

[编辑]阿伦·斯派克特参议员说,最高法院应该“判决更多的案件”。[216]另一方面,虽然斯卡利亚大法官在2009年的一次采访中承认,最高法院的如今听审案件的数量要比他加入最高法院时的数量要少。但他也表示,他没有改变其对案件审查的标准,他也不相信他的同事改变了他们的标准。他将1980年代后期的大量案件归咎于由法院通过的新联邦立法的早期波动。[247]

终身任期

[编辑]批评家拉里·萨巴托写道:“终身任期的绝对性,以及任命长期开庭审理案件的年轻律师,有上一代想法的高级法官比只有当代观点的法官好。”[227]桑福德·莱文森一直批评那些身体恶化却仍然在职的大法官。[255]詹姆斯·麦格雷戈·伯恩斯表示终身任期已经“严重滞后,最高法院在制度上几乎总是落后于时代”。[211]解决这些问题的提案包括由莱文森[256]和萨巴托[227][257]提出的大法官任职期限以及理查德·爱泼斯坦[258]等提出的强制退休年龄。[259]但是,其他人则认为,终身任期带来诸如公正和免受政治压力的实质性好处。亚历山大·汉密尔顿在联邦主义议文集第78号文件写道:“任何事情都不能像永久在职那般维持坚定和独立。”[260]

接受礼物

[编辑]在21世纪,增加了对大法官的接受昂贵礼品和旅行的审查。罗伯茨法院的所有成员都接受了旅行或礼物。2012年,索尼娅·索托马约尔大法官收到了来自于出版商Knopf Doubleday的190万美元预付款。[261]斯卡里亚大法官等曾接受由私人捐助者资助的数十次昂贵的异国旅行。[262]大法官以及对判决感兴趣的人一起参加由党派团体举办的私人活动,但却引起了参加活动期间不当交流的担忧。[263]同道会法律总监斯蒂芬·斯普尔丁指出:“这些旅行导致了公正问题,并涉及到了关于大法官的公正承诺。”[262]

著名案例

[编辑]- 罗诉韦德案

- 马伯利诉麦迪逊案

- 斯科特诉桑福德案

- 凯洛诉新伦敦市案

- 纽约时报诉沙利文案

- 普莱西诉弗格森案

- 布朗诉托皮卡教育局案

- 米兰达诉亚利桑那州案

- 劳伦斯诉得克萨斯州案

- 美国诉温莎案

- 奥贝格费尔诉霍奇斯案

参考文献

[编辑]引用

[编辑]- ^ The Court as an Institution - Supreme Court of the United States. www.supremecourt.gov. [2017-02-01]. (原始内容存档于2017-01-20).

- ^ Safire, William, "On language: POTUS and FLOTUS," New York Times, October 12, 1997 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). Retrieved August 27, 2013.

- ^ Code of Conduct for Justices November 13 2023 (PDF). [2023-11-14]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2024-03-08).

- ^ About the Supreme Court. Supreme Court of the United States. 2023-11-13 [2023-11-14]. (原始内容存档于2024-03-09).

- ^ Barnes, Robert; Marimow, Ann E. Supreme Court, under pressure, issues ethics code specific to justices. Washington Post. 2023-11-13 [2023-11-14].

- ^ Johnson, Barnabas. Almanac of the Federal Judiciary, p. 25 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) (Aspen Law & Business, 1988).

- ^ A Brief Overview of the Supreme Court (PDF). United States Supreme Court. [2009-12-31]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2017-07-06).

- ^ Bordewich, Fergus. The First Congress: How James Madison, George Washington, and a Group of Extraordinary Men Invented the Government. Simon & Schuster. 2016: 195. ISBN 1451691939.

- ^ Shugerman, Jed. "A Six-Three Rule: Reviving Consensus and Deference on the Supreme Court", Georgia Law Review, Vol. 37, p. 893 (2002–03).

- ^ Irons, Peter. A People's History of the Supreme Court, p. 101 (Penguin 2006).

- ^ Ashmore, Anne. Dates of Supreme Court decisions and arguments, United States Reports volumes 2–107 (1791–82) (PDF). Library, Supreme Court of the United States. August 2006 [2009-04-26]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2011-07-23).

- ^ Scott Douglas Gerber (editor). Seriatim: The Supreme Court Before John Marshall. New York University Press. 1998 [2009-10-31]. ISBN 0-8147-3114-7. (原始内容存档于2011-05-11).

(page 3) Finally many scholars cite the absence of a separate Supreme Court building as evidence that the early Court lacked prestige.

- ^ Manning, John F. The Eleventh Amendment and the Reading of Precise Constitutional Texts. Yale Law Journal. 2004, 113 (8): 1663–1750. doi:10.2307/4135780.

- ^ Epps, Garrett. Don't Do It, Justices. The Washington Post. 2004-10-24 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2008-10-13).

The court's prestige has been hard-won. In the early 1800s, Chief Justice John Marshall made the court respected

- ^ The Supreme Court had first used the power of judicial review in the case Ware v. Hylton, (1796), wherein it overturned a state law that conflicted with a treaty between the United States and Great Britain.

- ^ Rosen, Jeffrey. Black Robe Politics (book review of Packing the Court by James MacGregor Burns). Washington Post. 2009-07-05 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2011-02-09).

From the beginning, Burns continues, the Court has established its "supremacy" over the president and Congress because of Chief Justice John Marshall's "brilliant political coup" in Marbury v. Madison (1803): asserting a power to strike down unconstitutional laws.

- ^ The People's Vote: 100 Documents that Shaped America – Marbury v. Madison (1803). U.S. News & World Report. 2003 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2003-09-20).

With his decision in Marbury v. Madison, Chief Justice John Marshall established the principle of judicial review, an important addition to the system of "checks and balances" created to prevent any one branch of the Federal Government from becoming too powerful...A Law repugnant to the Constitution is void.

- ^ Sloan, Cliff; McKean, David. Why Marbury V. Madison Still Matters. Newsweek. 2009-02-21 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2009-08-02).

More than 200 years after the high court ruled, the decision in that landmark case continues to resonate.

- ^ The Constitution In Law: Its Phases Construed by the Federal Supreme Court (PDF). New York Times. 1893-02-27 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2011-04-30).

The decision … in Martin vs. Hunter's Lessee is the authority on which lawyers and Judges have rested the doctrine that where there is in question, in the highest court of a State, and decided adversely to the validity of a State statute... such claim is reviewable by the Supreme Court ...

- ^ Justices Ginsburg, Stevens, Souter, Breyer. Dissenting opinions in Bush v. Gore. USA Today. 2000-12-13 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2010-05-25).

Rarely has this Court rejected outright an interpretation of state law by a state high court … The Virginia court refused to obey this Court's Fairfax's Devisee mandate to enter judgment for the British subject's successor in interest. That refusal led to the Court's pathmarking decision in Martin v. Hunter's Lessee, 1 Wheat. 304 (1816).

- ^ 21.0 21.1 Decisions of the Supreme Court – Historic Decrees Issued in One Hundred an Eleven Years (PDF). New York Times. 1901-02-03 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2011-04-30).

Very important also was the decision in Martin vs. Hunter's lessee, in which the court asserted its authority to overrule, within certain limits, the decisions of the highest State courts.

- ^ The Supreme Quiz. Washington Post. 2000-10-02 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2012-05-30).

According to the Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States, Marshall's most important innovation was to persuade the other justices to stop seriatim opinions – each issuing one – so that the court could speak in a single voice. Since the mid-1940s, however, there's been a significant increase in individual "concurring" and "dissenting" opinions.

- ^ Slater, Dan. Justice Stevens on the Death Penalty: A Promise of Fairness Unfulfilled. Wall Street Journal. 2008-04-18 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2012-01-25).

The first Chief Justice, John Marshall set out to do away with seriatim opinions–a practice originating in England in which each appellate judge writes an opinion in ruling on a single case. (You may have read old tort cases in law school with such opinions). Marshall sought to do away with this practice to help build the Court into a coequal branch.

- ^ Suddath, Claire. A Brief History Of Impeachment. Time Magazine. 2008-12-19 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2009-04-30).

Congress tried the process again in 1804, when it voted to impeach Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase on charges of bad conduct. As a judge, Chase was overzealous and notoriously unfair … But Chase never committed a crime — he was just incredibly bad at his job. The Senate acquitted him on every count.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda. Rehnquist Joins Fray on Rulings, Defending Judicial Independence. New York Times. 1996-04-10 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2011-05-11).

the 1805 Senate trial of Justice Samuel Chase, who had been impeached by the House of Representatives … This decision by the Senate was enormously important in securing the kind of judicial independence contemplated by Article III" of the Constitution, Chief Justice Rehnquist said

- ^ Edward Keynes; with Randall K. Miller. The Court vs. Congress: Prayer, Busing, and Abortion. Duke University Press. 1989 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2011-05-11).

(page 115)... Grier maintained that Congress has plenary power to limit the federal courts' jurisdiction.

- ^ Ifill, Sherrilyn A. Sotomayor's Great Legal Mind Long Ago Defeated Race, Gender Nonsense. US News & World Report. 2009-05-27 [2009-10-31].

But his decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford doomed thousands of black slaves and freedmen to a stateless existence within the United States until the passage of the 14th Amendment. Justice Taney's coldly self-fulfilling statement in Dred Scott, that blacks had "no rights which the white man [was] bound to respect", has ensured his place in history—not as a brilliant jurist, but as among the most insensitive

- ^ Irons, Peter. A People's History of the Supreme Court: The Men and Women Whose Cases and Decisions Have Shaped Our Constitution. United States: Penguin Books. 2006: 176, 177. ISBN 0-14-303738-2.

The rhetorical battle that followed the Dred Scott decision, as we know, later erupted into the gunfire and bloodshed of the Civil War (p.176)... his opinion (Taney's) touched off an explosive reaction on both sides of the slavery issue... (p.177)

- ^ Liberty of Contract?. Exploring Constitutional Conflicts. 2009-10-31 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2009-11-22).

The term "substantive due process" is often used to describe the approach first used in Lochner—the finding of liberties not explicitly protected by the text of the Constitution to be impliedly protected by the liberty clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. In the 1960s, long after the Court repudiated its Lochner line of cases, substantive due process became the basis for protecting personal rights such as the right of privacy, the right to maintain intimate family relationships.

- ^ Adair v. United States 208 U.S. 161. Cornell University Law School. 1908 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2012-04-24).

No. 293 Argued: October 29, 30, 1907 --- Decided: January 27, 1908

- ^ Bodenhamer, David J.; James W. Ely. The Bill of Rights in modern America. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. 1993: 245. ISBN 978-0-253-35159-3.

… of what eventually became the 'incorporation doctrine,' by which various federal Bill of Rights guarantees were held to be implicit in the Fourteenth Amendment due process or equal protection.

- ^ White, Edward Douglass. Opinion for the Court, Arver v. U.S. 245 U.S. 366. [2017-07-01]. (原始内容存档于2011-05-01).

Finally, as we are unable to conceive upon what theory the exaction by government from the citizen of the performance of his supreme and noble duty of contributing to the defense of the rights and honor of the nation, as the result of a war declared by the great representative body of the people, can be said to be the imposition of involuntary servitude in violation of the prohibitions of the Thirteenth Amendment, we are constrained to the conclusion that the contention to that effect is refuted by its mere statement.

- ^ Siegan, Bernard H. The Supreme Court's Constitution. Transaction Publishers. 1987: 146 [2009-10-31]. ISBN 978-0-88738-671-8.

In the 1923 case of Adkins v. Children's Hospital, the court invalidated a classification based on gender as inconsistent with the substantive due process requirements of the fifth amendment. At issue was congressional legislation providing for the fixing of minimum wages for women and minors in the District of Columbia. (p.146)

- ^ Biskupic, Joan. Supreme Court gets makeover. USA Today. 2005-03-29 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2009-06-05).

The building is getting its first renovation since its completion in 1935.

- ^ Justice Roberts. Responses of Judge John G. Roberts, Jr. to the Written Questions of Senator Joseph R. Biden. Washington Post. 2005-09-21 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2013-01-24).

I agree that West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish correctly overruled Adkins. Lochner era cases – Adkins in particular – evince an expansive view of the judicial role inconsistent with what I believe to be the appropriately more limited vision of the Framers.

- ^ Lipsky, Seth. All the News That's Fit to Subsidize. Wall Street Journal. 2009-10-22 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2013-12-19).

He was a farmer in Ohio … during the 1930s, when subsidies were brought in for farmers. With subsidies came restrictions on how much wheat one could grow—even, Filburn learned in a landmark Supreme Court case, Wickard v. Filburn (1942), wheat grown on his modest farm.

- ^ Cohen, Adam. What's New in the Legal World? A Growing Campaign to Undo the New Deal. New York Times. 2004-12-14 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2013-03-07).

Some prominent states' rights conservatives were asking the court to overturn Wickard v. Filburn, a landmark ruling that laid out an expansive view of Congress's power to legislate in the public interest. Supporters of states' rights have always blamed Wickard … for paving the way for strong federal action...

- ^ United Press International. Justice Black Dies at 85; Served on Court 34 Years. New York Times. 1971-09-25 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2009-10-15).

Justice Black developed his controversial theory, first stated in a lengthy, scholarly dissent in 1947, that the due process clause applied the first eight amendments of the Bill of Rights to the states.

- ^ 100 Documents that Shaped America Brown v. Board of Education (1954). US News & World Report. 1954-05-17 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2009-11-06).

On May 17, 1954, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Earl Warren delivered the unanimous ruling in the landmark civil rights case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas. State-sanctioned segregation of public schools was a violation of the 14th amendment and was therefore unconstitutional. This historic decision marked the end of the "separate but equal" … and served as a catalyst for the expanding civil rights movement...

- ^ Essay: In defense of privacy. Time. 1966-07-15 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2009-10-13).

The biggest legal milestone in this field was last year's Supreme Court decision in Griswold v. Connecticut, which overthrew the state's law against the use of contraceptives as an invasion of marital privacy, and for the first time declared the "right of privacy" to be derived from the Constitution itself.

- ^ Gibbs, Nancy. America's Holy War. Time. 1991-12-09 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2009-05-10).

In the landmark 1962 case Engel v. Vitale, the high court threw out a brief nondenominational prayer composed by state officials that was recommended for use in New York State schools. "It is no part of the business of government", ruled the court, "to compose official prayers for any group of the American people to recite."

- ^ Mattox, William R., Jr; Trinko, Katrina. Teach the Bible? Of course.. USA Today. 2009-08-17 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2009-08-20).

Public schools need not proselytize — indeed, must not — in teaching students about the Good Book … In Abington School District v. Schempp, decided in 1963, the Supreme Court stated that "study of the Bible or of religion, when presented objectively as part of a secular program of education", was permissible under the First Amendment.

- ^ The Law: The Retroactivity Riddle. Time Magazine. 1965-06-18 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2011-02-03).

Last week, in a 7 to 2 decision, the court refused for the first time to give retroactive effect to a great Bill of Rights decision—Mapp v. Ohio (1961).

- ^ The Supreme Court: Now Comes the Sixth Amendment. Time. 1965-04-16 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2010-05-28).

Sixth Amendment's right to counsel (Gideon v. Wainwright in 1963). … the court said flatly in 1904: 'The Sixth Amendment does not apply to proceedings in state criminal courts." But in the light of Gideon … ruled Black, statements 'generally declaring that the Sixth Amendment does not apply to states can no longer be regarded as law.'

- ^ Guilt and Mr. Meese. New York Times. 1987-01-31 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2011-05-11).

1966 Miranda v. Arizona decision. That's the famous decision that made confessions inadmissible as evidence unless an accused person has been warned by police of the right to silence and to a lawyer, and waived it.

- ^ 存档副本 (PDF). [2016-02-06]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2017-06-21).

- ^ Earl M. Maltz, The Coming of the Nixon Court: The 1972 Term and the Transformation of Constitutional Law (University Press of Kansas; 2016)

- ^ O'Connor, Karen. Roe v. Wade: On Anniversary, Abortion Is out of the Spotlight. U.S. News & World Report. 2009-01-22 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2009-03-26).

The shocker, however, came in 1973, when the Court, by a vote of 7 to 2, relied on Griswold's basic underpinnings to rule that a Texas law prohibiting abortions in most situations was unconstitutional, invalidating the laws of most states. Relying on a woman's right to privacy...

- ^ Bakke Wins, Quotas Lose. Time. 1978-07-10 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2010-10-14).

Split almost exactly down the middle, the Supreme Court last week offered a Solomonic compromise. It said that rigid quotas based solely on race were forbidden, but it also said that race might legitimately be an element in judging students for admission to universities. It thus approved the principle of 'affirmative action'…

- ^ Time to Rethink Buckley v. Valeo. New York Times. 1998-11-12 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2011-05-11).

...Buckley v. Valeo. The nation's political system has suffered ever since from that decision, which held that mandatory limits on campaign spending unconstitutionally limit free speech. The decision did much to promote the explosive growth of campaign contributions from special interests and to enhance the advantage incumbents enjoy over underfunded challengers.

- ^ 51.0 51.1 Staff writer. Supreme Court Justice Rehnquist's Key Decisions. Washington Post. 1972-06-29 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2010-05-25).

Furman v. Georgia … Rehnquist dissents from the Supreme Court conclusion that many state laws on capital punishment are capricious and arbitrary and therefore unconstitutional.

- ^ History of the Court, in Hall, Ely Jr., Grossman, and Wiecek (eds) The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. Oxford University Press, 1992, ISBN 0-19-505835-6

- ^ A Supreme Revelation. Wall Street Journal. 2008-04-19 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2009-12-01).

Thirty-two years ago, Justice John Paul Stevens sided with the majority in a famous "never mind" ruling by the Supreme Court. Gregg v. Georgia, in 1976, overturned Furman v. Georgia, which had declared the death penalty unconstitutional only four years earlier.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda. The Chief Justice on the Spot. New York Times. 2009-01-08 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2011-05-12).

The federalism issue at the core of the new case grows out of a series of cases from 1997 to 2003 in which the Rehnquist court applied a new level of scrutiny to Congressional action enforcing the guarantees of the Reconstruction amendments.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda. William H. Rehnquist, Chief Justice of Supreme Court, Is Dead at 80. New York Times. 2005-09-04 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2011-04-30).

United States v. Lopez in 1995 raised the stakes in the debate over federal authority even higher. The decision declared unconstitutional a Federal law, the Gun Free School Zones Act of 1990, that made it a federal crime to carry a gun within 1,000 feet of a school.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda. The Rehnquist Court and Its Imperiled States' Rights Legacy. New York Times. 2005-06-12 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2011-05-05).

Intrastate activity that was not essentially economic was beyond Congress's reach under the Commerce Clause, Chief Justice Rehnquist wrote for the 5-to-4 majority in United States v. Morrison.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda. Inmates Who Follow Satanism and Wicca Find Unlikely Ally. New York Times. 2005-03-22 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2011-04-30).

His (Rehnquist's) reference was to a landmark 1997 decision, City of Boerne v. Flores, in which the court ruled that the predecessor to the current law, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, exceeded Congress's authority and was unconstitutional as applied to the states.

- ^ Amar, Vikram David. Casing John Roberts. New York Times. 2005-07-27 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2008-10-14).

SEMINOLE TRIBE v. FLORIDA (1996) In this seemingly technical 11th Amendment dispute about whether states can be sued in federal courts, Justice O'Connor joined four others to override Congress's will and protect state prerogatives, even though the text of the Constitution contradicts this result.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda. Justices Seem Ready to Tilt More Toward States in Federalism. New York Times. 1999-04-01 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2011-05-11).

The argument in this case, Alden v. Maine, No. 98-436, proceeded on several levels simultaneously. On the surface … On a deeper level, the argument was a continuation of the Court's struggle over an even more basic issue: the Government's substantive authority over the states.

- ^ Lindenberger, Michael A. The Court's Gay Rights Legacy. Time Magazine. [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2009-11-07).

The decision in the Lawrence v. Texas case overturned convictions against two Houston men, whom police had arrested after busting into their home and finding them engaged in sex. And for the first time in their lives, thousands of gay men and women who lived in states where sodomy had been illegal were free to be gay without being criminals.

- ^ Justice Sotomayor. Retire the 'Ginsburg rule' – The 'Roe' recital. USA Today. 2009-07-16 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2009-08-22).

The court's decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey reaffirmed the court holding of Roe. That is the precedent of the court and settled, in terms of the holding of the court.

- ^ Kamiya, Gary. Against the Law. Salon.com. 2001-07-04 [2012-11-21]. (原始内容存档于2012-10-13).

...the remedy was far more harmful than the problem. By stopping the recount, the high court clearly denied many thousands of voters who cast legal votes, as defined by established Florida law, their constitutional right to have their votes counted. … It cannot be a legitimate use of law to disenfranchise legal voters when recourse is available. …

- ^ Krauthammer, Charles. The Winner in Bush v. Gore?. Time Magazine. 2000-12-18 [2009-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2010-11-22).

Re-enter the Rehnquist court. Amid the chaos, somebody had to play Daddy. … the Supreme Court eschewed subtlety this time and bluntly stopped the Florida Supreme Court in its tracks—and stayed its willfulness. By , mind you, …

- ^ Babington, Charles; Baker, Peter. Roberts Confirmed as 17th Chief Justice. Washington Post. 2005-09-30 [2009-11-01]. (原始内容存档于2010-01-16).

John Glover Roberts Jr. was sworn in yesterday as the 17th chief justice of the United States, enabling President Bush to put his stamp on the Supreme Court for decades to come, even as he prepares to name a second nominee to the nine-member court.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda. In Steps Big and Small, Supreme Court Moved Right. New York Times. 2007-07-01 [2009-11-01]. (原始内容存档于2009-04-17).

It was the Supreme Court that conservatives had long yearned for and that liberals feared … This was a more conservative court, sometimes muscularly so, sometimes more tentatively, its majority sometimes differing on methodology but agreeing on the outcome in cases big and small.

- ^ Savage, Charlie. Respecting Precedent, or Settled Law, Unless It's Not Settled. New York Times. 2009-07-14 [2009-11-01]. (原始内容存档于2011-05-11).

Gonzales v. Carhart — in which the Supreme Court narrowly upheld a federal ban on the late-term abortion procedure opponents call "partial birth abortion" — to be settled law.

- ^ A Bad Day for Democracy. The Christian Science Monitor. [2010-01-22]. (原始内容存档于2010-01-25).

- ^ Barnes, Robert. Justices to Decide if State Gun Laws Violate Rights. Washington Post. 2009-10-01 [2009-11-01]. (原始内容存档于2011-05-03).

The landmark 2008 decision to strike down the District of Columbia's ban on handgun possession was the first time the court had said the amendment grants an individual right to own a gun for self-defense. But the 5 to 4 opinion in District of Columbia v. Heller...

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda. Justice Stevens Renounces Capital Punishment. New York Times. 2008-04-18 [2009-11-01]. (原始内容存档于2008-12-11).

His renunciation of capital punishment in the lethal injection case, Baze v. Rees, was likewise low key and undramatic.

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda. Supreme Court Rejects Death Penalty for Child Rape. New York Times. 2008-06-26 [2009-11-01]. (原始内容存档于2008-12-11).

The death penalty is unconstitutional as a punishment for the rape of a child, a sharply divided Supreme Court ruled Wednesday … The 5-to-4 decision overturned death penalty laws in Louisiana and five other states.

- ^ 16 Stat. 44

- ^ Mintz, S. The New Deal in Decline. Digital History. University of Houston. 2007 [2009-10-27]. (原始内容存档于2008-05-05).

- ^ Hodak, George. February 5, 1937: FDR Unveils Court Packing Plan. ABAjournal.com. American Bar Association. 2007 [2009-01-29]. (原始内容存档于2011-08-15).

- ^ "Justices, Number of", in Hall, Ely Jr., Grossman, and Wiecek (editors), The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. Oxford University Press 1992, ISBN 0-19-505835-6

- ^ 美国宪法第二条第2款第2项。

- ^ United States Senate. "Nominations". [2017-07-02]. (原始内容存档于2017-07-07).

- ^ Jim Brunner. Sen. Patty Murray will oppose Neil Gorsuch for Supreme Court. The Seattle Times. 2017-03-24 [2017-04-09]. (原始内容存档于2017-04-10).

In a statement Friday morning, Murray cited Republicans' refusal to confirm or even seriously consider President Obama's nomination of Judge Merrick Garland, a similarly well-qualified jurist — and went on to lambaste President Trump's conduct in his first few months in office. [...] And Murray added she's "deeply troubled" by Gorsuch's "extreme conservative perspective on women's health," citing his "inability" to state a clear position on Roe v. Wade, the landmark abortion-legalization decision, and his comments about the "Hobby Lobby" decision allowing employers to refuse to provide birth-control coverage.

- ^ McCaskill, Claire. Gorsuch:Good for corporations, bad for working people. 2017-03-31 [2017-04-09]. (原始内容存档于2017-04-08).

I cannot support Judge Gorsuch because a study of his opinions reveal a rigid ideology that always puts the little guy under the boot of corporations. He is evasive, but his body of work isn't. Whether it is a freezing truck driver or an autistic child, he has shown a stunning lack of humanity. And he has been an activist - for example, writing a dissent on a case that had been settled, in what appears to be an attempt to audition for his current nomination.

- ^ Schallhorn, Kaitlyn. Schumer: Democrats will filibuster SCOTUS nominee Neil Gorsuch. The Blaze. 2017-03-23 [2017-04-07]. (原始内容存档于2017-04-10).

Schumer added that Gorsuch's record shows he has a "deep-seated conservative ideology" and "groomed by the Federalist Society," a conservative nonprofit legal organization.

- ^ Matt Flegenheimer. Senate Republicans Deploy 'Nuclear Option' to Clear Path for Gorsuch. New York Times. 2017-04-06 [2017-07-02]. (原始内容存档于2018-10-02).

After Democrats held together Thursday morning and filibustered President Trump's nominee, Republicans voted to lower the threshold for advancing Supreme Court nominations from 60 votes to a simple majority.

- ^ U.S. Senate: Supreme Court Nominations, Present-1789. United States Senate. [2017-04-08]. (原始内容存档于2017-02-21).

- ^ 美国法典第5编 § 第2902节.

- ^ 美国法典第28编 § 第4节. If two justices are commissioned on the same date, then the oldest one has precedence.

- ^ Balkin, Jack M. The passionate intensity of the confirmation process. Jurist. [2008-02-13]. (原始内容存档于2007-12-18).

- ^ The Stakes Of The 2016 Election Just Got Much, Much Higher. The Huffington Post. [2016-02-14]. (原始内容存档于2016-02-14).

- ^ McMillion, Barry J. Supreme Court Appointment Process: Senate Debate and Confirmation Vote (PDF). Congressional Research Service. 2015-10-19 [2016-02-14]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2015-12-28).

- ^ Hall, Kermit L. (编). Appendix Two. Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. Oxford University Press. 1992: 965–971. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- ^ See, e.g., Evans v. Stephens, 387 F.3d 1220 (11th Cir. 2004), which concerned the recess appointment of William Pryor. Concurring in denial of certiorari, Justice Stevens observed that the case involved "the first such appointment of an Article III judge in nearly a half century" 544 U.S. 942 (2005) (Stevens, J., concurring in denial of cert) (internal quotation marks deleted).

- ^ 89.0 89.1 Fisher, Louis. Recess Appointments of Federal Judges (PDF). CRSN Report for Congress. Congressional Research Service (The Library of Congress). 2001-09-05,. RL31112: 16– [2010-08-06]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2010-08-04).

Resolved, That it is the sense of the Senate that the making of recess appointments to the Supreme Court of the United States may not be wholly consistent with the best interests of the Supreme Court, the nominee who may be involved, the litigants before the Court, nor indeed the people of the United States, and that such appointments, therefore, should not be made except under unusual circumstances and for the purpose of preventing or ending a demonstrable breakdown in the administration of the Court's business.

- ^ The resolution passed by a vote of 48 to 37, mainly along party lines; Democrats supported the resolution 48–4, and Republicans opposed it 33–0.

- ^ National Relations Board v. Noel Canning et al (PDF): 34, 35. [2017-07-02]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2017-07-28). In the opinion for the Court, Breyer states "In our view, however, the pro forma sessions count as sessions, not as periods of recess. We hold that, for purposes of the Recess Appointments Clause, the Senate is in session when it says it is, provided that, under its own rules, it retains the capacity to transact Senate business. The Senate met that standard here." Later, the opinion states: "For these reasons, we conclude that we must give great weight to the Senate's own determination of when it is and when it is not in session. But our deference to the Senate cannot be absolute. When the Senate is without the capacity to act, under its own rules, it is not in session even if it so declares."

- ^ Obama Won't Appoint Scalia Replacement While Senate Is Out This Week. NPR.org. [2017-01-25]. (原始内容存档于2016-11-17) (英语).

- ^ How the Federal Courts Are Organized: Can a federal judge be fired?. Federal Judicial Center. fjc.gov. [2012-03-18]. (原始内容存档于2012-09-15).

- ^ History of the Federal Judiciary: Impeachments of Federal Judges. Federal Judicial Center fjc.gov. [2012-03-18]. (原始内容存档于2010-12-08).

- ^ Appel, Jacob M. Anticipating the Incapacitated Justice. Huffington Post. 2009-08-22 [2009-08-23]. (原始内容存档于2009-08-27).

- ^ Ali, Ambreen. How Presidents Influence the Court. Congress.org. 2010-06-16 [2010-06-16]. (原始内容存档于2010-06-18).

- ^

- Oriana González; Danielle Alberti. Estimated ideologies of Supreme Court justices. Axios. 2023-07-03 (英语).

- Vincent M. Bonventre. 6 to 3: The Impact of the Supreme Court’s Conservative Super-Majority. 纽约州律师公会. 2023-10-31 [2024-10-28] (美国英语).

- Who are the justices on the US Supreme Court?. BBC. 2015-06-17 [2024-10-28] (英国英语).

- ^ Walthr, Matthew. Sam Alito: A Civil Man. The American Spectator. 2014-04-21 [2017-06-15]. (原始内容存档于2017-05-22) –通过The ANNOTICO Reports.

- ^ DeMarco, Megan. Growing up Italian in Jersey: Alito reflects on ethnic heritage. The Times of Trenton, New Jersey. 2008-02-14 [2017-06-15]. (原始内容存档于2017-07-30).

- ^ 戈萨奇原本信奉天主教,但在婚后参加美国圣公会的教堂。Daniel Burke. What is Neil Gorsuch's religion? It's complicated. CNN.com. 2017-03-22 [2017-07-02]. (原始内容存档于2017-06-25).

Springer said she doesn't know whether Gorsuch considers himself a Catholic or an Episcopalian. "I have no evidence that Judge Gorsuch considers himself an Episcopalian, and likewise no evidence that he does not." Gorsuch's younger brother, J.J., said he too has "no idea how he would fill out a form. He was raised in the Catholic Church and confirmed in the Catholic Church as an adolescent, but he has been attending Episcopal services for the past 15 or so years."

- ^ Religion of the Supreme Court. adherents.com. 2006-01-31 [2010-07-09]. (原始内容存档于2019-08-09).

- ^ Segal, Jeffrey A.; Spaeth, Harold J. The Supreme Court and the Attitudinal Model Revisited. Cambridge Univ. Press. 2002: 183. ISBN 0-521-78971-0.

- ^ Schumacher, Alvin. Roger B. Taney. Encyclopaedia Britannica. [2017-05-03]. (原始内容存档于2017-08-24).

He was the first Roman Catholic to serve on the Supreme Court.

- ^ 104.0 104.1 104.2 104.3 104.4 FAQs - Supreme Court Justices. 美国最高法院. [2020-11-10]. (原始内容存档于2017-08-04).

- ^ Baker, Peter. Kagan Is Sworn in as the Fourth Woman, and 112th Justice, on the Supreme Court. New York Times. 2010-08-07 [2010-08-08]. (原始内容存档于2010-08-07).

- ^ O'Brien, David M. Storm Center: The Supreme Court in American Politics 6th. W.W. Norton & Company. 2003: 46. ISBN 0-393-93218-4.

- ^ de Vogue, Ariane. Clarence Thomas' Supreme Court legacy. CNN. 2016-10-22 [2017-05-03]. (原始内容存档于2017-04-02).

- ^ 108.0 108.1 The Four Justices. Smithsonian Institution. [2017-05-03]. (原始内容存档于2016-08-20).

- ^ Tapper, Jake; de Vogue, Ariane; Zeleny, Jeff; Klein, Betsy; Vazquez, Maegan. Biden nominates Ketanji Brown Jackson to be first Black woman to sit on Supreme Court. CNN. 2022-02-25 [2022-02-28]. (原始内容存档于2022-02-28).

- ^ David N. Atkinson, Leaving the Bench (University Press of Kansas 1999) ISBN 0-7006-0946-6

- ^ Greenhouse, Linda. An Invisible Chief Justice. The New York Times. 2010-09-09 [2010-09-09]. (原始内容存档于2010-09-11).

Had [O'Connor] anticipated that the chief justice would not serve out the next Supreme Court term, she told me after his death, she would have delayed her own retirement for a year rather than burden the court with two simultaneous vacancies. […] Her reason for leaving was that her husband, suffering from Alzheimer's disease, needed her care at home.

- ^ Ward, Artemus. Deciding to Leave: The Politics of Retirement from the United States Supreme Court. SUNY Press. 2003: 358 [2017-07-02]. ISBN 978-0-7914-5651-4. (原始内容存档于2017-07-03).

One byproduct of the increased [retirement benefit] provisions [in 1954], however has been a dramatic rise in the number of justices engaging in succession politics by trying to time their departures to coincide with a compatible president. The most recent departures have been partisan, some more blatantly than others, and have bolstered arguments to reform the process. A second byproduct has been an increase in justices staying on the Court past their ability to adequately contribute.[1] p. 9

- ^ Stolzenberg, Ross M.; Lindgren, James. Retirement and Death in Office of U.S. Supreme Court Justices. Demography. May 2010, 47 (2): 269–298. PMC 3000028

. PMID 20608097. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0100.

. PMID 20608097. doi:10.1353/dem.0.0100. If the incumbent president is of the same party as the president who nominated the justice to the Court, and if the incumbent president is in the first two years of a four-year presidential term, then the justice has odds of resignation that are about 2.6 times higher than when these two conditions are not met.

- ^ See for example Sandra Day O'Connor:How the first woman on the Supreme Court became its most influential justice, by Joan Biskupic, Harper Collins, 2005, p. 105. Also Rookie on the Bench: The Role of the Junior Justice by Clare Cushman, Journal of Supreme Court History 32 no. 3 (2008), pp. 282–296.

- ^ Breyer Just Missed Record as Junior Justice. [2008-01-11]. (原始内容存档于2008-01-26).

- ^ Judicial Compensation. United States Courts. [2021-12-06]. (原始内容存档于2021-11-03).

- ^ Bill Mears. Take a look through Neil Gorsuch's judicial record. FoxNews.com. 2017-03-20 [2017-07-02]. (原始内容存档于2017-05-22).

A Fox News analysis of that record -- including some 3,000 rulings he has been involved with -- reveals a solid, predictable conservative philosophy, something President Trump surely was attuned to when he nominated him to fill the open ninth seat. The record in many ways mirrors the late Justice Antonin Scalia's approach to constitutional and statutory interpretation.

- ^ Cope, Kevin; Fischman, Joshua. It's hard to find a federal judge more conservative than Brett Kavanaugh. The Washington Post. 2018-09-05 [2020-11-02]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-10).

Kavanaugh served a dozen years on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, a court viewed as first among equals of the 12 federal appellate courts. Probing nearly 200 of Kavanaugh's votes and over 3000 votes by his judicial colleagues, our analysis shows that his judicial record is significantly more conservative than that of almost every other judge on the D.C. Circuit. That doesn't mean that he'd be the most conservative justice on the Supreme Court, but it strongly suggests that he is no judicial moderate.

- ^ Chamberlain, Samuel. Trump nominates Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court. Fox News. 2018-07-09 [2020-11-02]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-07).

Trump may have been swayed in part because of Kavanaugh's record of being a reliable conservative on the court – and reining in dozens of administrative decisions of the Obama White House. There are some question marks for conservatives, particularly an ObamaCare ruling years ago.

- ^ Thomson-Devaux, Amelia; Bronner, Laura; Wiederkehr, Anna. How conservative is Amy Coney Barrett?. FiveThirtyEight. 2020-10-14 [2020-10-27]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-11).

We can look to her track record on the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, though, for clues. Barrett has served on that court for almost three years now, and two different analyses of her rulings point to the same conclusion: Barrett is one of the more conservative judges on the circuit — and maybe even the most conservative.

- ^ Betz, Bradford. Chief Justice Roberts' recent votes raise doubts about 'conservative revolution' on Supreme Court. Fox News. 2019-03-02 [2020-11-02]. (原始内容存档于2020-11-18).

Erwin Chemerinsky, a law professor at the University of California at Berkeley, told Bloomberg that Roberts' recent voting record may indicate that he is taking his role as the median justice "very seriously" and that the recent period was "perhaps the beginning of his being the swing justice."

- ^ Roeder, Oliver. How Kavanugh will change the Supreme Court. FiveThirtyEight. 2018-10-06 [2020-11-02]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-07).

Based on what we know about measuring the ideology of justices and judges, the Supreme Court will soon take a hard and quick turn to the right. It's a new path that is likely to last for years. Chief Justice John Roberts, a George W. Bush appointee, will almost certainly become the new median justice, defining the court's new ideological center.

- ^ Goldstein, Tom. Everything you read about the Supreme Court is wrong (except here, maybe). SCOTUSblog. 2010-06-30 [2010-07-07]. (原始内容存档于2010-07-07).

- ^ Among the examples mentioned by Goldstein for the 2009 term were:

- Dolan v. United States, which interpreted judges' prerogatives broadly, typically a "conservative" result. The majority consisted of the five junior Justices: Thomas, Ginsburg, Breyer, Alito, and Sotomayor.

- Magwood v. Patterson, which expanded habeas corpus petitions, a "liberal" result, in an opinion by Thomas, joined by Stevens, Scalia, Breyer, and Sotomayor.

- Shady Grove Orthopedic Associates v. Allstate Insurance Co., which yielded a pro-plaintiff result in an opinion by Scalia joined by Roberts, Stevens, Thomas, and Sotomayor.

- ^ 125.0 125.1 October 2011 Term, Five to Four Decisions (PDF). SCOTUSblog. 2012-06-30 [2012-07-02]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-10-02).

- ^ 126.0 126.1 Final October 2010 Stat Pack available. SCOTUSblog. 2011-06-27 [2011-06-28]. (原始内容存档于2011-07-01).

- ^ End of Term statistical analysis – October 2010 (PDF). SCOTUSblog. 2011-07-01 [2011-07-02]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2011-09-17).

- ^ Cases by Vote Split (PDF). SCOTUSblog. 2011-06-27 [2011-06-28]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2011-10-26).

- ^ Justice agreement – Highs and Lows (PDF). SCOTUSblog. 2011-06-27 [2011-06-28]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2011-10-26).

- ^ Justice agreement (PDF). SCOTUSblog. 2011-06-27 [2011-06-28]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2011-10-26).

- ^ Frequency in the majority (PDF). SCOTUSblog. 2011-06-27 [2011-06-28]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2011-10-26).

- ^ Five-to-Four cases (PDF). SCOTUSblog. 2011-06-27 [2011-06-28]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2011-10-26).

- ^ October 2011 term, Cases by votes split (PDF). SCOTUSblog. 2012-06-30 [2012-07-02]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-12-01).

- ^ October 22011 term, Strength of the Majority (PDF). SCOTUSblog. 2012-06-30 [2012-07-02]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2012-12-01).

- ^ Bhatia, Kedar. October Term 2012 summary memo. SCOTUSblog. 2013-06-29 [2013-06-29]. (原始内容存档于2013-06-30).

- ^ Final October Term 2012 Stat Pack (PDF). SCOTUSblog. 2013-06-27 [2013-06-27]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-11-05).

- ^ 137.0 137.1 137.2 137.3 Plan Your Trip (quote:) "In mid-May, after the oral argument portion of the Term has concluded, the Court takes the Bench Mondays at 10AM for the release of orders and opinions.". US Senator John McCain. 2009-10-24 [2009-10-24]. (原始内容存档于2009-10-30).

- ^ 138.0 138.1 138.2 Visiting the Court. Supreme Court of the United States. 2010-03-18 [2010-03-19]. (原始内容存档于2010-03-22).

- ^ Visiting-Capitol-Hill. docstoc. 2009-10-24 [2009-10-24]. (原始内容存档于2016-08-21).

- ^ How The Court Works. The Supreme Court Historical Society. 2009-10-24 [2014-01-31]. (原始内容存档于2014-02-03).

- ^

- ^ Liptak, Adam. Supreme Court Declines to Hear Challenge to Colorado's Marijuana Laws. New York Times. 2016-03-21 [2017-04-27]. (原始内容存档于2016-03-24).

- ^

- ^ United States v. Shipp, 203 U.S. 563 (Supreme Court of the United States 1906).

- ^ 145.0 145.1 145.2 Curriden, Mark. A Supreme Case of Contempt. ABA Journal. American Bar Association. 2009-06-02 [2017-04-27]. (原始内容存档于2017-04-27).

On May 28, [U.S. Attorney General William] Moody did something unprecedented, then and now. He filed a petition charging Sheriff Shipp, six deputies and 19 leaders of the lynch mob with contempt of the Supreme Court. The justices unanimously approved the petition and agreed to retain original jurisdiction in the matter. ... May 24, 1909, stands out in the annals of the U.S. Supreme Court. On that day, the court announced a verdict after holding the first and only criminal trial in its history.

- ^ 146.0 146.1 Hindley, Meredith. Chattanooga versus the Supreme Court: The Strange Case of Ed Johnson. Humanities (National Endowment for the Humanities). November 2014, 35 (6) [2017-04-27]. (原始内容存档于2017-04-27).

United States v. Shipp stands out in the history of the Supreme Court as an anomaly. It remains the only time the Court has conducted a criminal trial.

- ^ Linder, Douglas. United States v. Shipp (U.S. Supreme Court, 1909). Famous Trials. [2017-04-27]. (原始内容存档于2017-04-27).

- ^ 美国法典第28编 § 第1254节

- ^ 美国法典第28编 § 第1259节

- ^ 美国法典第28编 § 第1258节

- ^ 美国法典第28编 § 第1260节

- ^ 152.0 152.1 美国法典第28编 § 第1257节

- ^ Brannock, Steven; Weinzierl, Sarah. Confronting a PCA: Finding a Path Around a Brick Wall (PDF). Stetson Law Review. 2003, XXXII: 368–369, 387–390 [2017-04-27]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2016-08-04).

- ^ Gutman, Jeffrey. Federal Practice Manual for Legal Aid Attorneys: 3.3 Mootness. Federal Practice Manual for Legal Aid Attorneys. Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law. [2017-04-27]. (原始内容存档于2017-04-27).

- ^ Miscellaneous Order (6/30/2022) (PDF). Supreme Court of the United States. [2022-06-30]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-06-30).

- ^ 美国法典第28编 § 第1254节

- ^ 美国法典第28编 § 第1257节; see also Adequate and independent state grounds

- ^ James, Robert A. Instructions in Supreme Court Jury Trials (PDF). The Green Bag. 2d. 1998, 1 (4): 378 [2013-02-05]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-08-18).

- ^ 美国法典第28编 § 第1872节 See Georgia v. Brailsford, 3 U.S. 1 (1794), in which the Court conducted a jury trial.

- ^ Mauro, Tony. Roberts Dips Toe Into Cert Pool. Legal Times. 2005-10-21 [2007-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2009-06-02).

- ^ Tony Mauro. Justice Alito Joins Cert Pool Party. Legal Times. 2006-07-04 [2007-10-31]. (原始内容存档于2007-09-30).

- ^ Liptak, Adam. A Second Justice Opts Out of a Longtime Custom: The 'Cert. Pool'. New York Times. 2008-09-25 [2008-10-17]. (原始内容存档于2009-04-17).

- ^ Liptak, Adam. Gorsuch, in sign of independence, is out of Supreme Court's clerical pool. New York Times. 2017-05-01 [2017-05-02]. (原始内容存档于2017-05-02).

- ^ For example, the arguments on the constitutionality of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act took place over three days and lasted over six hours, covering several issues; the arguments for Bush v. Gore were 90 minutes long; oral arguments in United States v. Nixon lasted three hours; and the Pentagon papers case was given a two-hour argument. Christy, Andrew. 'Obamacare' will rank among the longest Supreme Court arguments ever. NPR. 2011-11-15 [2011-03-31]. (原始内容存档于2011-11-16). The longest modern-day oral arguments were in the case of California v. Arizona, in which oral arguments lasted over sixteen hours over four days in 1962.Bobic, Igor. Oral arguments on health reform longest in 45 years. Talking Points Memo. 2012-03-26 [2014-01-31]. (原始内容存档于2014-02-04).

- ^ Glazer, Eric M.; Zachary, Michael. Joining the Bar of the U.S. Supreme Court. Volume LXXI, No. 2. Florida Bar Journal: 63. February 1997 [2014-02-03]. (原始内容存档于2014-04-05).

- ^ Gresko, Jessica. For lawyers, the Supreme Court bar is vanity trip. Florida Today (Melbourne, Florida). 2013-03-24: 2A. (原始内容存档于2013-03-23).

- ^ How The Court Works; Library Support. The Supreme Court Historical Society. [2014-02-03]. (原始内容存档于2014-02-21).

- ^ See generally, Tushnet, Mark, ed. (2008) I Dissent: Great Opposing Opinions in Landmark Supreme Court Cases, Malaysia: Beacon Press, pp. 256, ISBN 978-0-8070-0036-6

- ^ Kessler, Robert. Why Aren't Cameras Allowed at the Supreme Court Again?. The Atlantic. [2017-03-24]. (原始内容存档于2017-03-25).

- ^ Johnson, Benny. The 2016 Running of the Interns. Independent Journal Review. [2017-03-24]. (原始内容存档于2017-03-25).

- ^ 美国法典第28编 § 第1节

- ^ 美国法典第28编 § 第2109节

- ^ Pepall, Lynne; Richards, Daniel L.; Norman, George. Industrial Organization: Contemporary Theory and Practice. Cincinnati: South-Western College Publishing. 1999: 11–12.

- ^ Bound Volumes. Supreme Court of the United States. [2019-01-09]. (原始内容存档于2019-01-08).

- ^ Cases adjudged in the Supreme Court at October Term, 2012 – March 26 through June 13, 2013 (PDF). United States Reports. 2018, 569 [2019-01-09]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2021-03-31).

- ^ Sliplists. Supreme Court of the United States. [2019-01-01]. (原始内容存档于2017-04-06).

- ^ Supreme Court Research Guide. law.georgetown.edu. Georgetown Law Library. [2012-08-22]. (原始内容存档于2012-08-22).

- ^ How to Cite Cases: U.S. Supreme Court Decisions. lib.guides.umd.edu. University of Maryland University Libraries. [2012-08-22]. (原始内容存档于2012-08-22).

- ^ Kermit L. Hall; Kevin T. McGuire (编). Institutions of American Democracy: The Judicial Branch. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. 2005: 117–118 [2017-07-03]. ISBN 978-0-19-530917-1. (原始内容存档于2016-11-23).

- ^ 180.0 180.1 Kermit L. Hall; Kevin T. McGuire (编). Institutions of American Democracy: The Judicial Branch. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. 2005: 118 [2017-07-03]. ISBN 978-0-19-530917-1. (原始内容存档于2016-11-23).

- ^ Mendelson, Wallace. Separation of Powers. Hall, Kermit L. (编). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. Oxford University Press. 1992: 775. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- ^ The American Conflict by Horace Greeley (1873), p. 106; also in The Life of Andrew Jackson (2001) by Robert Vincent Remini

- ^ Vile, John R. Court curbing. Hall, Kermit L. (编). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. Oxford University Press. 1992: 202. ISBN 0-19-505835-6.

- ^ 184.0 184.1 184.2 184.3 Peppers, Todd C. Courtiers of the Marble Palace: The Rise and Influence of the Supreme Court Law Clerk. Stanford University Press. 2006: 195, 1, 20, 22, and 22–24 respectively. ISBN 978-0-8047-5382-1.

- ^ Weiden, David; Ward, Artemus. Sorcerers' Apprentices: 100 Years of Law Clerks at the United States Supreme Court. NYU Press. 2006 [2017-07-03]. ISBN 978-0-8147-9404-3. (原始内容存档于2016-01-01).

- ^ Chace, James. Acheson: The Secretary of State Who Created the American World. New York: Simon & Schuster. 2007: 441998. ISBN 978-0-684-80843-7.

- ^ List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States

- ^ 188.0 188.1 188.2 188.3 Liptak, Adam. Polarization of Supreme Court Is Reflected in Justices' Clerks. The New York Times. 2010-09-07 [2010-09-07]. (原始内容存档于2011-05-12).

- ^ William E. Nelson; Harvey Rishikof; I. Scott Messinger; Michael Jo. The Liberal Tradition of the Supreme Court Clerkship: Its Rise, Fall, and Reincarnation? (PDF). Vanderbilt Law Review: 1749. November 2009 [2010-09-07]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2010-07-27).

|volume=被忽略 (帮助);|issue=被忽略 (帮助) - ^ Liptak and Kopicki, The New York Times, June 7, 2012 Approval Rating for Justices Hits Just 44% in New Poll (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ 191.0 191.1 191.2 See for example "Judicial activism" in The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States, edited by Kermit Hall; article written by Gary McDowell

- ^ Root, Damon W. Lochner and Liberty. Wall Street Journal. 2009-09-21 [2009-10-23]. (原始内容存档于2009-10-01).

- ^ Steinfels, Peter. 'A Church That Can and Cannot Change': Dogma. New York Times: Books. 2005-05-22 [2009-10-22]. (原始内容存档于2011-05-11).

- ^ Savage, David G. Roe vs. Wade? Bush vs. Gore? What are the worst Supreme Court decisions?. Los Angeles Times. 2008-10-23 [2009-10-23]. (原始内容存档于2008-10-23).

a lack of judicial authority to enter an inherently political question that had previously been left to the states

- ^ Lewis, Neil A. Judicial Nominee Says His Views Will Not Sway Him on the Bench. New York Times. 2002-09-19 [2009-10-22]. (原始内容存档于2011-05-11).

he has written scathingly of Roe v. Wade

- ^ Election Guide 2008: The Issues: Abortion. New York Times. 2008 [2009-10-22]. (原始内容存档于2008-09-16).