P63

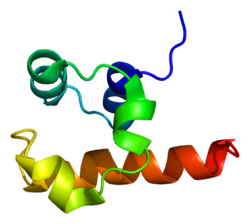

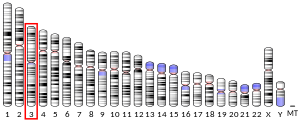

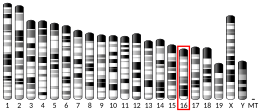

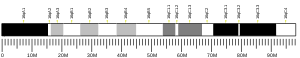

p63,亦作TP63,全称肿瘤蛋白p63(tumor protein p63)或恶性转化相关蛋白63(transformation-related protein 63),在人体内由TP63基因编码[6][7][8][9]。p63的发现是在p53基因发现后20年。p63与p53、p73同属一个蛋白家族,三者结构与功能都较为相似[10]。尽管p63的发现晚于p53,但进化生物学的证据表明p63是p53蛋白家族的起源,p53、p73都是由p63蛋白演化而成[11]。

功能

[编辑]p63是p53蛋白家族下的一种转录因子。p63-/-基因型的小鼠会出现无牙、乳腺等发育依赖间充质-上皮相互作用的器官组织及无附肢等多种发育缺陷。p63蛋白的转录变体主要有两种,TAp63和ΔNp63。已证明ΔNp63拥有多种功能,包括参与皮肤发育和成体干细胞/祖细胞的功能调控[12]。相比之下,传统的观点认为TAp63的功能几乎只局限于参与凋亡过程。不过,近期的研究还表明TAp63参与了卵母细胞完整性的维持[13]。另一些研究还表明TAp63参与了心脏发育[14]和早衰过程[15]。

临床意义

[编辑]p63蛋白的突变可能会导致兔唇、腭裂等发育畸形[16]。p63蛋白的突变可导致以等裂兔唇为典型特征的EEC综合征(ectrodactyly-ectodermal dysplasia-cleft syndrom)[16]。此外,p63蛋白的突变也可能导致3型兔唇腭裂综合征(EEC3)、先天性缺指(ectrodactyly,亦称为裂手-脚畸形4),以及以等裂兔唇为典型特征的AEC综合征[16]。此外,ADULT综合征(Acro–dermato–ungual–lacrimal–tooth syndrome)、附肢-乳腺综合征(limb-mammary syndrome)、RHS综合征(Rap-Hodgkin syndrome)以及也与p63蛋白功能的异常有关。目前认为兔唇、腭裂是同时出现还是任出现一种取决于p63的不同突变[16]近期,研究人员提出使用iPS细胞分化替代缺陷型上皮细胞治疗EEC综合征的方法[17]。

诊断

[编辑]p63的免疫组化法可以用于诊断扁平细胞癌和前列腺腺癌(最常见的一种前列腺癌)[18]。正常的前列腺腺体含有基底细胞,因而组织高表达p63,免疫染色深,而恶性转化后的腺癌组织因缺少基底细胞,p63免疫染色呈现阴性结果[19]。p63亦可用于鉴别腺癌、小细胞癌中常见的分化程度低的癌变扁平细胞[20]。

相互作用

[编辑]p63可与HNRPAB蛋白发生相互作用[21]。同样,p63可以通过与转录因子IRF6增强子结合激活其转录[16]。

调节

[编辑]研究表明p63的表达受miRNAmiR-203的调控[22][23]。

参见

[编辑]- AMACR,另一种前列腺癌的肿瘤标志物

参考文献

[编辑]- ^ 與P63相關的疾病;在維基數據上查看/編輯參考.

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000073282 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000022510 - Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ Human PubMed Reference:. National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Mouse PubMed Reference:. National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Yang A, Kaghad M, Wang Y, Gillett E, Fleming MD, Dötsch V, Andrews NC, Caput D, McKeon F. p63, a p53 homolog at 3q27-29, encodes multiple products with transactivating, death-inducing, and dominant-negative activities. Molecular Cell. Sep 1998, 2 (3): 305–16. PMID 9774969. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80275-0.

- ^ Osada M, Ohba M, Kawahara C, Ishioka C, Kanamaru R, Katoh I, Ikawa Y, Nimura Y, Nakagawara A, Obinata M, Ikawa S. Cloning and functional analysis of human p51, which structurally and functionally resembles p53. Nature Medicine. Jul 1998, 4 (7): 839–43. PMID 9662378. doi:10.1038/nm0798-839.

- ^ Zeng X, Zhu Y, Lu H. NBP is the p53 homolog p63. Carcinogenesis. Feb 2001, 22 (2): 215–9. PMID 11181441. doi:10.1093/carcin/22.2.215.

- ^ Tan M, Bian J, Guan K, Sun Y. p53CP is p51/p63, the third member of the p53 gene family: partial purification and characterization. Carcinogenesis. Feb 2001, 22 (2): 295–300. PMID 11181451. doi:10.1093/carcin/22.2.295.

- ^ Wu G, Nomoto S, Hoque MO, Dracheva T, Osada M, Lee CC, Dong SM, Guo Z, Benoit N, Cohen Y, Rechthand P, Califano J, Moon CS, Ratovitski E, Jen J, Sidransky D, Trink B. DeltaNp63alpha and TAp63alpha regulate transcription of genes with distinct biological functions in cancer and development. Cancer Research. May 2003, 63 (10): 2351–7. PMID 12750249.

- ^ Skipper M. Dedicated protection for the female germline. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. January 2007, 8 (1): 4–5. doi:10.1038/nrm2091.

- ^ Crum CP, McKeon FD. p63 in epithelial survival, germ cell surveillance, and neoplasia. Annual Review of Pathology. 2010, 5: 349–71. PMID 20078223. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathol-121808-102117.

- ^ Deutsch GB, Zielonka EM, Coutandin D, Weber TA, Schäfer B, Hannewald J, Luh LM, Durst FG, Ibrahim M, Hoffmann J, Niesen FH, Sentürk A, Kunkel H, Brutschy B, Schleiff E, Knapp S, Acker-Palmer A, Grez M, McKeon F, Dötsch V. DNA damage in oocytes induces a switch of the quality control factor TAp63α from dimer to tetramer. Cell. Feb 2011, 144 (4): 566–76. PMC 3087504

. PMID 21335238. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.013.

. PMID 21335238. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2011.01.013.

- ^ Rouleau M, Medawar A, Hamon L, Shivtiel S, Wolchinsky Z, Zhou H, De Rosa L, Candi E, de la Forest Divonne S, Mikkola ML, van Bokhoven H, Missero C, Melino G, Pucéat M, Aberdam D. TAp63 is important for cardiac differentiation of embryonic stem cells and heart development. Stem Cells. Nov 2011, 29 (11): 1672–83 [2017-11-13]. PMID 21898690. doi:10.1002/stem.723. (原始内容存档于2014-08-08).

- ^ Su X, Paris M, Gi YJ, Tsai KY, Cho MS, Lin YL, Biernaskie JA, Sinha S, Prives C, Pevny LH, Miller FD, Flores ER. TAp63 prevents premature aging by promoting adult stem cell maintenance. Cell Stem Cell. Jul 2009, 5 (1): 64–75. PMC 3418222

. PMID 19570515. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.003.

. PMID 19570515. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.003.

- ^ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Dixon MJ, Marazita ML, Beaty TH, Murray JC. Cleft lip and palate: understanding genetic and environmental influences. Nature Reviews Genetics. Mar 2011, 12 (3): 167–78. PMC 3086810

. PMID 21331089. doi:10.1038/nrg2933.

. PMID 21331089. doi:10.1038/nrg2933.

- ^ Shalom Feuerstein R. et al. Impaired epithelial differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells from EEC patients is rescued by APR-246/PRIMA-1MET. P.N.A.S 2012. 存档副本. [2014-12-13]. (原始内容存档于2014-12-14).

- ^ Shiran MS, Tan GC, Sabariah AR, Rampal L, Phang KS. p63 as a complimentary basal cell specific marker to high molecular weight-cytokeratin in distinguishing prostatic carcinoma from benign prostatic lesions. The Medical Journal of Malaysia. Mar 2007, 62 (1): 36–9. PMID 17682568.

- ^ Herawi M, Epstein JI. Immunohistochemical antibody cocktail staining (p63/HMWCK/AMACR) of ductal adenocarcinoma and Gleason pattern 4 cribriform and noncribriform acinar adenocarcinomas of the prostate. The American Journal of Surgical Pathology. Jun 2007, 31 (6): 889–94. PMID 17527076. doi:10.1097/01.pas.0000213447.16526.7f.

- ^ Zhang H, Liu J, Cagle PT, Allen TC, Laga AC, Zander DS. Distinction of pulmonary small cell carcinoma from poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinoma: an immunohistochemical approach. Modern Pathology. Jan 2005, 18 (1): 111–8. PMID 15309021. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800251.

- ^ Fomenkov A, Huang YP, Topaloglu O, Brechman A, Osada M, Fomenkova T, Yuriditsky E, Trink B, Sidransky D, Ratovitski E. P63 alpha mutations lead to aberrant splicing of keratinocyte growth factor receptor in the Hay-Wells syndrome. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. Jun 2003, 278 (26): 23906–14. PMID 12692135. doi:10.1074/jbc.M300746200.

- ^ Yi R, Poy MN, Stoffel M, Fuchs E. A skin microRNA promotes differentiation by repressing 'stemness'. Nature. Mar 2008, 452 (7184): 225–9. PMID 18311128. doi:10.1038/nature06642.

- ^ Aberdam D, Candi E, Knight RA, Melino G. miRNAs, 'stemness' and skin. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. Dec 2008, 33 (12): 583–91 [2017-11-13]. PMID 18848452. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2008.09.002. (原始内容存档于2013-04-21).

拓展阅读

[编辑]- Little NA, Jochemsen AG. p63. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. Jan 2002, 34 (1): 6–9. PMID 11733180. doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00086-3.

- van Bokhoven H, McKeon F. Mutations in the p53 homolog p63: allele-specific developmental syndromes in humans. Trends in Molecular Medicine. Mar 2002, 8 (3): 133–9. PMID 11879774. doi:10.1016/S1471-4914(01)02260-2.

- van Bokhoven H, Brunner HG. Splitting p63. American Journal of Human Genetics. Jul 2002, 71 (1): 1–13. PMC 384966

. PMID 12037717. doi:10.1086/341450.

. PMID 12037717. doi:10.1086/341450. - Brunner HG, Hamel BC, van Bokhoven H. P63 gene mutations and human developmental syndromes. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Oct 2002, 112 (3): 284–90. PMID 12357472. doi:10.1002/ajmg.10778.

- Jacobs WB, Walsh GS, Miller FD. Neuronal survival and p73/p63/p53: a family affair. The Neuroscientist. Oct 2004, 10 (5): 443–55. PMID 15359011. doi:10.1177/1073858404263456.

- Zusman I. The soluble p51 protein in cancer diagnosis, prevention and therapy. In Vivo. 2005, 19 (3): 591–8. PMID 15875781.

- Morasso MI, Radoja N. Dlx genes, p63, and ectodermal dysplasias. Birth Defects Research. Part C, Embryo Today. Sep 2005, 75 (3): 163–71. PMC 1317295

. PMID 16187309. doi:10.1002/bdrc.20047.

. PMID 16187309. doi:10.1002/bdrc.20047. - Barbieri CE, Pietenpol JA. p63 and epithelial biology. Experimental Cell Research. Apr 2006, 312 (6): 695–706. PMID 16406339. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.11.028.

- Shalom-Feuerstein R, Lena AM, Zhou H, De La Forest Divonne S, Van Bokhoven H, Candi E, Melino G, Aberdam D. ΔNp63 is an ectodermal gatekeeper of epidermal morphogenesis. Cell Death and Differentiation. May 2011, 18 (5): 887–96. PMC 3131930

. PMID 21127502. doi:10.1038/cdd.2010.159.

. PMID 21127502. doi:10.1038/cdd.2010.159.