髓磷脂

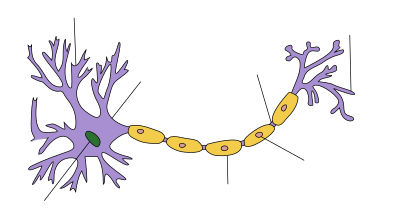

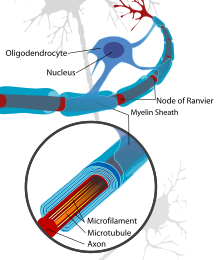

髓磷脂(英语:myelin)又称髓鞘质,是包绕在神经元胞突(主要是轴突,以及部分树突)外部的膜外物质,由30%蛋白质和70%的各类脂质组成,后者主要含有鞘氨醇、脑苷脂、脂肪酸和磷脂酰胆碱(少数为磷脂酰乙醇胺)等[1]。完全围绕胞突周长的髓磷脂会组成髓鞘(myelin sheath),其功能与电线的绝缘体外皮相似,但不同的是髓鞘每隔一段距离便有中断部分,形成一节一节的形状,髓鞘包裹中断的部分称为“兰氏结”(Ranvier's node),兰氏结之间被髓鞘包裹的胞突部分称为“结间段”(internodal segment或internode)。兰氏结位置曝露的神经元细胞膜可以正常的去极化,使得动作电位沿着胞突上的兰氏结依次形成,产生速度更快(100~120米/秒,相比于无髓鞘的0.5~10米/秒)的跳跃式传导。

髓磷脂由神经胶质细胞生产,在脊椎动物的中枢神经和周围神经系统中分别由寡突胶质细胞(oligodendrocyte)和神经膜细胞(neurolemmocyte,也称施旺细胞 Schwann's cell)形成髓鞘。感觉神经元无论是树突或轴突都有髓鞘,但其轴突明显比较短,因为感觉神经元要把外面的感觉传进来到细胞本体,再经由轴突传到下一个细胞,因此树突很长。运动神经元的树突连接着联络神经元的轴突所以比较短,但其轴突较长且具有髓鞘[2]。联络神经元的轴突则是没有髓鞘的。

髓鞘是有颌类脊椎动物最普遍的特征之一,但一些无脊椎动物(比如对虾、长臂虾、哲水蚤和寡毛类环节动物)的神经胶质细胞也可以形成髓鞘,其中囊对虾更是有着动物界最快的神经传导速度(可达200米/秒,将近脊椎动物的两倍),但区别是脊椎动物的髓鞘通常会覆盖胞突整体,而且除兰氏结外不会有任何孔隙;无脊椎动物的髓鞘则有孔且只会覆盖部分胞突。髓鞘使得动物可以在体型演化变大的同时仍能维持足够敏捷的感官反应和运动协调,是脊椎动物得以在泥盆纪后占据各个生态环境的上层生态位的关键因素之一(其它关键因素是颌、心脏和高集权度脑的演化)。

功能

[编辑]

目前知道髓鞘的功能有三:

- 滋养轴突与周围的神经组织(神经胶质细胞的基本功能);

- 在相邻的轴突之间形成电气绝缘,降低电容并增加细胞膜内外的电阻,避免受干扰产生信号丧失,并通过跳跃式传导来加快动作电位的传递[3];

- 在一些轴突受损萎缩的情况下保留原有的轴突路线及突触位点,以利引导轴突的再生。

被髓鞘覆盖的轴突段(节间段)的细胞膜缺少电压门控型钠离子通道,但在兰氏结区域的钠离子通道却极其密集[4]。当阳性的钠离子通过兰氏结进入轴突内后会导致去极化(此时膜电位会从-70 mV变为约+35 mV[4]),随后钠离子沿着轴突的细胞质迅速扩散,最终改变下一个兰氏结的静息电位并引发又一次去极化,使得动作电位依着一个个兰氏结进行跳跃式的快速传递,并且每次都会得到重新增强[5]。在动作电位传过后,电压门控钾离子通道会打开让膜电位先恢复正常,然后再由钠钾泵逐渐将细胞膜内外的离子浓度恢复初始状态。

除了给轴突“绝缘”以外,髓鞘细胞还可以起到促进中间纤维磷酸化的作用,有助于增大节间段的轴突直径;同时髓鞘可以帮助增加兰氏结区域化学分子的聚集度,提高去极化的规模[6],并调节轴突内部细胞骨架和细胞器(比如线粒体)的运输[7]。在2012年,研究发现了髓鞘有“滋养”轴突功能的证据[8][9],可以提供钠钾泵耗能交换所需的能量[10][11]。

因为周边神经是多个髓鞘纵列支持一根轴突,因此会在神经路径上形成一条成形的“导管”。当周边神经受损(特别是被锐器切断)后,只要这条髓鞘管仍然完好,在理论上可以引导神经再生并提供让原有功能恢复的可能性。但因为神经和肌肉之间的触突并不会因此完全复原,所以即使神经轴突能够再生,也需要大量康复性的训练治疗去重新学习动作技能。而中枢神经因为通常是每个髓鞘细胞要支持多根轴突,很难复原神经路径,所以几乎无法引导神经再生[12]。

成分

[编辑]

中枢神经髓鞘的成分与周围神经稍有不同,但两者都起到同样的绝缘功能。因为富含脂类,髓鞘在中枢神经中呈现白色,因而得名“白质”(与之相应的是由神经元胞体组成的“灰质”)。中枢神经中的神经束(如胼胝体和视束)和周围神经(如坐骨神经和听觉神经)都属于白质,由成千上万的髓鞘轴突平行排列组成,其间还包括星状细胞和微胶细胞等不参与形成髓鞘的其它胶质细胞。这些白质束需要血液供应养分和氧气,并且对外力(比如受压)十分敏感。

髓鞘大约有40%的质量由水组成,排除水分外的干重含有60~75%的脂质和15~25%的蛋白质。髓鞘中的脂质主体是一种糖脂——半乳糖脑苷脂,由交织成链的鞘磷脂巩固,而胆固醇是形成髓鞘的必需成分[13]。中枢神经白质中的蛋白质包括髓鞘碱性蛋白(myelin basic protein,简称MBP)[14]、髓鞘少突胶质细胞糖蛋白(myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein,简称MOG)[15]和蛋白脂蛋白(proteolipid protein,简称PLP)[16];而在周围神经的白质中,髓磷脂零蛋白(myelin protein zero,简称MPZ或P0)起到与中枢神经PLP相似的功能。

生长

[编辑]

在中枢神经系统中,寡突胶质细胞是由少突先驱胶质细胞(OPC)分化形成[17][18][19]。在周围神经系统中,神经膜细胞由施万前驱细胞(SCP)分化形成,源于从神经管两侧向身体各处迁移的神经嵴细胞[20]。

智人的髓鞘生长始于妊娠第三期[21],但新生儿的中枢和周围神经中几乎没有成形的髓鞘。在婴儿时期髓鞘开始加速生成,随之一起增长的是认知、语言沟通和动作技能(比如爬行和步行)的快速成熟。髓鞘生长在青少年至青年时期基本完成,但大脑皮质的髓鞘化可以根据神经可塑性的不同和后天的训练学习延续至青壮年时期,甚至终生[22][23][24]。

另见

[编辑]参考文献

[编辑]- ^ [1][失效链接]

- ^ 存档副本 (PDF). [2018-01-14]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-02-22).

- ^ Hartline DK. What is myelin?. Neuron Glia Biology. May 2008, 4 (2): 153–63. PMID 19737435. S2CID 33164806. doi:10.1017/S1740925X09990263.

- ^ 4.0 4.1 Saladin KS. Anatomy & physiology: the unity of form and function 6th. New York: McGraw-Hill. 2012.[页码请求]

- ^ Raine CS. Characteristics of Neuroglia. Siegel GJ, Agranoff BW, Albers RW, Fisher SK, Uhler MD (编). Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects 6th. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven. 1999 [2024-11-30]. (原始内容存档于2024-06-04).

- ^ Brivio V, Faivre-Sarrailh C, Peles E, Sherman DL, Brophy PJ. Assembly of CNS Nodes of Ranvier in Myelinated Nerves Is Promoted by the Axon Cytoskeleton. Current Biology. April 2017, 27 (7): 1068–73. Bibcode:2017CBio...27.1068B. PMC 5387178

. PMID 28318976. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.025.

. PMID 28318976. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2017.01.025.

- ^ Stassart RM, Möbius W, Nave KA, Edgar JM. The Axon-Myelin Unit in Development and Degenerative Disease. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2018, 12: 467. PMC 6050401

. PMID 30050403. doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.00467

. PMID 30050403. doi:10.3389/fnins.2018.00467  .

.

- ^ Fünfschilling U, Supplie LM, Mahad D, Boretius S, Saab AS, Edgar J, Brinkmann BG, Kassmann CM, Tzvetanova ID, Möbius W, Diaz F, Meijer D, Suter U, Hamprecht B, Sereda MW, Moraes CT, Frahm J, Goebbels S, Nave KA. Glycolytic oligodendrocytes maintain myelin and long-term axonal integrity. Nature. April 2012, 485 (7399): 517–21. Bibcode:2012Natur.485..517F. PMC 3613737

. PMID 22622581. doi:10.1038/nature11007.

. PMID 22622581. doi:10.1038/nature11007.

- ^ Lee Y, Morrison BM, Li Y, Lengacher S, Farah MH, Hoffman PN, Liu Y, Tsingalia A, Jin L, Zhang PW, Pellerin L, Magistretti PJ, Rothstein JD. Oligodendroglia metabolically support axons and contribute to neurodegeneration. Nature. July 2012, 487 (7408): 443–48. Bibcode:2012Natur.487..443L. PMC 3408792

. PMID 22801498. doi:10.1038/nature11314.

. PMID 22801498. doi:10.1038/nature11314.

- ^ Engl E, Attwell D. Non-signalling energy use in the brain. The Journal of Physiology. August 2015, 593 (16): 3417–329. PMC 4560575

. PMID 25639777. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2014.282517.

. PMID 25639777. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2014.282517.

- ^ Attwell D, Laughlin SB. An energy budget for signaling in the grey matter of the brain. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism. October 2001, 21 (10): 1133–45. PMID 11598490. doi:10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001

.

.

- ^ Huebner, Eric A.; Strittmatter, Stephen M. Axon Regeneration in the Peripheral and Central Nervous Systems. Results and Problems in Cell Differentiation. 2009, 48: 339–51. ISBN 978-3-642-03018-5. ISSN 0080-1844. PMC 2846285

. PMID 19582408. doi:10.1007/400_2009_19.

. PMID 19582408. doi:10.1007/400_2009_19.

- ^ Saher G, Brügger B, Lappe-Siefke C, Möbius W, Tozawa R, Wehr MC, Wieland F, Ishibashi S, Nave KA. High cholesterol level is essential for myelin membrane growth. Nature Neuroscience. April 2005, 8 (4): 468–75. PMID 15793579. S2CID 9762771. doi:10.1038/nn1426.

- ^ Steinman L. Multiple sclerosis: a coordinated immunological attack against myelin in the central nervous system. Cell. May 1996, 85 (3): 299–302. PMID 8616884. S2CID 18442078. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81107-1

.

.

- ^ Mallucci G, Peruzzotti-Jametti L, Bernstock JD, Pluchino S. The role of immune cells, glia and neurons in white and gray matter pathology in multiple sclerosis. Progress in Neurobiology. April 2015,. 127–128: 1–22. PMC 4578232

. PMID 25802011. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.02.003.

. PMID 25802011. doi:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2015.02.003.

- ^ Greer JM, Lees MB. Myelin proteolipid protein – the first 50 years. The International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. March 2002, 34 (3): 211–15. PMID 11849988. doi:10.1016/S1357-2725(01)00136-4.

- ^ Nishiyama A, Komitova M, Suzuki R, Zhu X. Polydendrocytes (NG2 cells): multifunctional cells with lineage plasticity. Nature Reviews. Neuroscience. January 2009, 10 (1): 9–22. PMID 19096367. S2CID 15264205. doi:10.1038/nrn2495.

- ^ Swiss VA, Nguyen T, Dugas J, Ibrahim A, Barres B, Androulakis IP, Casaccia P. Feng Y , 编. Identification of a gene regulatory network necessary for the initiation of oligodendrocyte differentiation. PLOS ONE. April 2011, 6 (4): e18088. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...618088S. PMC 3072388

. PMID 21490970. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018088

. PMID 21490970. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018088  .

.

- ^ Buller B, Chopp M, Ueno Y, Zhang L, Zhang RL, Morris D, Zhang Y, Zhang ZG. Regulation of serum response factor by miRNA-200 and miRNA-9 modulates oligodendrocyte progenitor cell differentiation. Glia. December 2012, 60 (12): 1906–1914. PMC 3474880

. PMID 22907787. doi:10.1002/glia.22406.

. PMID 22907787. doi:10.1002/glia.22406.

- ^ Solovieva, Tatiana; Bronner, Marianne. Schwann cell precursors: Where they come from and where they go. Cells & Development. 2021-06, 166: 2667–2901. doi:10.1016/j.cdev.2021.203729.

- ^ Pediatric Neurologic Examination Videos & Descriptions: Developmental Anatomy. library.med.utah.edu. [2016-08-20]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-16).

- ^ Swire M, French-Constant C. Seeing Is Believing: Myelin Dynamics in the Adult CNS. Neuron. May 2018, 98 (4): 684–86. PMID 29772200. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.005

.

.

- ^ Hill RA, Li AM, Grutzendler J. Lifelong cortical myelin plasticity and age-related degeneration in the live mammalian brain. Nature Neuroscience. May 2018, 21 (5): 683–95. PMC 5920745

. PMID 29556031. doi:10.1038/s41593-018-0120-6.

. PMID 29556031. doi:10.1038/s41593-018-0120-6.

- ^ Hughes EG, Orthmann-Murphy JL, Langseth AJ, Bergles DE. Myelin remodeling through experience-dependent oligodendrogenesis in the adult somatosensory cortex. Nature Neuroscience. May 2018, 21 (5): 696–706. PMC 5920726

. PMID 29556025. doi:10.1038/s41593-018-0121-5.

. PMID 29556025. doi:10.1038/s41593-018-0121-5.

- Fields, R. Douglas, "The Brain Learns in Unexpected Ways: Neuroscientists have discovered a set of unfamiliar cellular mechanisms for making fresh memories", Scientific American, vol. 322, no. 3 (March 2020), pp. 74–79. "Myelin, long considered inert insulation on axons, is now seen as making a contribution to learning by controlling the speed at which signals travel along neural wiring." (p. 79.)

- Swire M, Ffrench-Constant C. Seeing Is Believing: Myelin Dynamics in the Adult CNS. Neuron. May 2018, 98 (4): 684–86. PMID 29772200. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.005

.

. - Waxman SG. Conduction in myelinated, unmyelinated, and demyelinated fibers. Archives of Neurology. October 1977, 34 (10): 585–89. PMID 907529. doi:10.1001/archneur.1977.00500220019003.