放射齿目

| 放射齿目 | |

|---|---|

| |

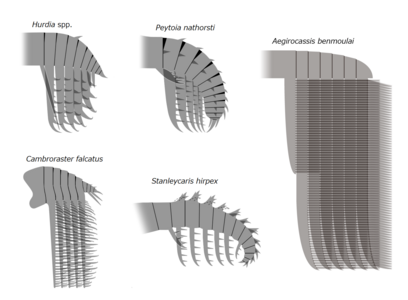

| 七个放射齿目物种的复原图(未依比例显示) 由左至右,自上而下分别为: | |

| 科学分类 | |

| 界: | 动物界 Animalia |

| 门: | 节肢动物门 Arthropoda |

| 纲: | †恐虾纲 Dinocaridida |

| 目: | †放射齿目 Radiodonta Collins, 1996 |

| 科 | |

不属于任何科的属 | |

| 寒武纪大爆发 |

|---|

|

放射齿目(学名:Radiodonta),又称射口类[1]、奇虾类[1]、奇虾动物[2],是节肢动物一个已灭绝的基群(有时亦被划入叶足动物门下),属于恐虾纲,其下共计19个有效属。放射齿目的化石在欧、亚、非、北美等大洲,以及澳洲等地皆有发现,涵盖的时间跨度由寒武世一直延伸至泥盆世,长达1.2亿年;最著名的放射齿类动物奇虾,便是寒武世的代表性生物之一。

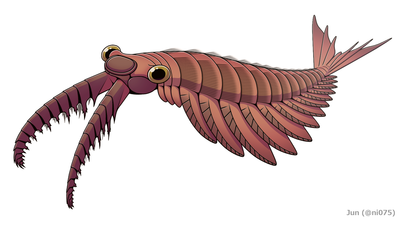

放射齿目体型从不及10厘米至2米皆有,身型可分为头、躯干两个体节。其中,头部长有复眼和骨化的前附肢,以及齿环绕四周的口锥;躯干则分为许多小节,每节各有一对由肌肉束控制的扇鳍。此类群也有由肠道、消化腺组成的消化系统,和眼节附近的大脑等结构组成的神经系统。据其形态推测,放射齿目可以利用扇鳍在水中游动,有的甚至可以利用其尾扇快速转向。觅食时,它们有的能利用前附肢抓取猎物,有的能从海底泥中滤取食物碎屑,还有的能够滤食浮游生物。

放射齿目作为研究节肢动物起源和早期系统发育的重要类群,其分类方式在分类学研究中获高度关注。然而,它们的化石极难保存下来,因此出现过不少分类错误。[3]

词源与俗名

[编辑]放射齿目的学名“Radiodonta ”来自拉丁语“radius”(轮辐)和希腊语“odoús”(齿),这指的是其放射状分布的牙齿[4],但并非所有该目生物均有此特征[5][6]。

本目的俗名包含“radiodonts”[5][7][8]、“radiodontans”[6][9]、“radiodontids”[4]。此外,鉴于放射齿目至今19个有效属中绝大多数都属于奇虾亚目(Anomalocarida),一些英文文献也会直接称之为“anomalocaridids”[10][11][12] 或 “anomalocarids”[13],中文又译为奇虾类[1]或奇虾动物[2]。

定义

[编辑]1996年,加拿大古生物学家戴斯蒙·柯林斯建立恐虾纲与放射齿目,当时柯林斯将放射齿目定义为:[4]

放射齿目是两侧对称、体型修长的节肢动物,其未矿化的表皮在口颚、爪子处尤为坚韧。放射齿目的身体可分为两个体段,类似螯肢亚门节肢动物的头胸部和腹部。通常来讲,前体段没有明显的外部分节,口前长有一对爪,一对突出的复眼,以及位于腹侧带有辐射状牙齿。有几种放射齿目动物还拥有额外的一层牙齿,以及三、四对后口咀嚼式附肢。躯干分节,通常为13节,节的两侧生有片状的结构用以游泳,以及用以呼吸的鳃。尾部可能有三片向外突出的结构。有些物种躯体上生有咀嚼式附肢。

2014 年,学者以系统发生学的角度定义了放射齿目:任何亲缘关系比堪察加拟石蟹更接近加拿大奇虾皆为放射齿目[13]。2019 年,学者以形态学的角度定义了放射齿目:头甲复合结构(head carapace complex) 包含 H骨片(H-element) 和 P骨片(P-element);前附肢棘(endites) 生有前附肢辅棘(auxiliary spines);前端的扇鳍(flaps) 或刚毛叶(setal blades) 退化;躯体梯形,前端较高,往后渐低[8]。

特征

[编辑]

绝大多数的放射齿目动物都比其他的寒武纪动物大得多,身长通常介于30至50厘米之间[7]。已知最大的放射齿目是奥陶纪的本莫拉海神盔虾(Aegirocassis benmoulai),其最大体长可达两米[12]。最小的放射齿目之一是8厘米的里拉琴虫属,有爪里拉琴虫(L. unguispinus) 的幼体只有1.8厘米[14]。

放射齿目动物的身体可以分成两个部分:头部和躯干。头部只有一节体节[15],称作“眼节”(ocular somite),眼节被骨片覆盖,覆盖眼节的骨片统称“头甲复合结构”(head carapace complex),眼节前侧生有分节的附肢,腹侧生有口器(口锥,oral cone),还有眼柄和复眼。躯干呈梯形,越往后越低,每节体节都生有一对扇鳍(flap) 和名为刚毛叶(setal blades) 的鳃状结构[8]。

前附肢

[编辑]

头前侧生有一对前附肢(frontal appendage),前人研究中曾称该对附肢为“爪”(claws)、“取食足”(feeding appendages)、“大附肢”(great appendage),但近期的文献不再使用大附肢一词,因为学者认为放射齿目的前附肢与大附肢纲的大附肢不同源[15]。前附肢骨化且分节,大部分附肢上有一节一节的称作分节(podomeres) 腹侧上有棘,称作“前附肢棘”(endites),该棘的前侧和后侧可能会额外生有数排棘,称作“前附肢辅棘”(auxiliary spines)[16]。前附肢可分为两部分,梗节(shaft) 和端节(distal articulated region)[16],梗节为靠近头部的部分,端节为延伸出去的部分。有些物种腹部具有三角状的节间膜,可使躯体更为柔软灵活[17]。放射齿目眼前节(与第一大脑相关)与有爪动物门的主触角和真节肢动物(Euarthropoda) 的上唇同源,都起源于眼节;而上述结构则与螯肢亚门的螯肢和其他节肢动物的触角和大附肢不同源,这些结构起源于第一眼后节(与第二大脑相关)[11][15]。前附肢的形态因物种而异,尤其前附肢棘差异更大,因此前附肢和前附肢棘为分辨物种的重要特征[16]。甚至有些放射齿目的物种是单靠前附肢标本发表的,例如高跷双棘虾(Ursulinacaris grallae)、抱怪虫属中的史蒂芬山抱怪虫(Amplectobelua stephenensis)[16][17]。

-

奇虾科、抱怪虫科和其他近缘物种的前附肢

-

筛虾科的前附肢

-

赫德虾科的前附肢

口器

[编辑]

口器位于头部的腹侧,前附肢的着生点之后。口器周围环绕着一圈齿,这种形式的口器称作“口锥”(oral cone),旧文献中称作“颚(jaws)”。有些物种会有三或四齿增大,让口器外形呈现三向(如奇虾属)或四向(如赫德虾属)的辐射对称[14][18]。齿的内部朝向口器开口的地方生有刺,有些赫德虾科的齿内刺比其他物种来得多层[8][10]。抱怪虫科的口器细节复原图是推测而来,实际的口器可能为非典型的辐射对称[5][6]。

头部骨片、复眼和躯体

[编辑]

头甲复合结构由三个骨片组成:中央的 H 骨片(前侧骨片或头盾)和一对 P 骨片(两侧骨片),H 骨片包覆头部背侧,P 骨片包覆头部两侧的腹面[8]。有些物种的两个 P 骨片和 H 骨片相连,形成一个狭窄的前侧延伸,称作“P 骨片颈”(P-elements neck)或“喙桥”(beak)[8][10]。奇虾科和抱怪虫科的头甲复合结构较小,且呈卵形[8][6],赫德虾科的较大[8]。头部生有一对眼柄,着生于 H 骨片和 P 骨片后侧的间隙[8][10],眼柄末端生有复眼,学者推测眼柄可移动[19]。

不同于原始描述的是,放射齿目的体躯分节十分明显[8][9][12],没有任何放射齿目的具有足状附肢[20](除了瓜肢虫属,但该属是否属于放射齿目还未有定论[12][21])。体躯分很多节,呈梯形,由前向后渐低,前三或前四节隘缩,形成颈部[8]。

躯体两侧生有鳍状附肢,称作“扇鳍”(flaps),有些文献称作“侧鳍”(lateral flaps)和“叶”(lobes),通常一个体节会有一对扇鳍,扇鳍的前侧会和前一个扇鳍的后侧稍微重叠,有些赫德虾科的物种背侧会生有一列不和前一个扇鳍重叠的小扇鳍[12]。扇鳍生有无数条线状结构,称作“线状支撑结构”(strengthening rays[8][9][12])。颈上的扇鳍称作“前鳍”(anterior flaps)或“颈鳍”(neck flaps),前扇鳍明显退化。有些物种具有“咀嚼式结构”(gnathobase-like structures, GLSs),咀嚼式结构着生于前扇鳍的基部[5][6]。背上有列状的“刚毛叶”(setal blades or lamellae)[8],刚毛叶是由无数的细长结构排列而成,似鳃,刚毛叶附盖在体节的背侧[12]。

腹侧的扇鳍可能与真节肢动物的内足(endopod) 和叶足动物的叶足(lobopod) 同源,而背侧的扇鳍和刚毛叶可能与真节肢动物的外足(exopod)和叶足动物背侧生有鳃的扇鳍(gill-bearing dorsal flaps)同源[12][22]。躯体末端的结构因物种而异,可能会有以下形态:一至三对的尾扇[8][20]、两条细长的尾毛(furcae)[8] [23]、一条延长的尾部结构(terminal structure[20]) 或没有其他突出物的圆滑尾端[12]。

-

赫德虾科的三个成员:海神盔虾(上)、皮托虾(左下)与赫德虾(右下),三者皆生有背部的翼鳍和发达的头甲复合结构。

-

加拿大奇虾(Anomalocaris canadensis),其头甲复合结构呈现卵形,体末生有三对尾鳍和一条尾须(terminal tailpiece)。

-

双肢抱怪虫(Amplectobelua symbrachiata),具有咀嚼式结构和两条尾须。

内部结构

[编辑]

有些放射齿目化石可见肌肉束、消化系统和神经系统。每个体节的两侧生有一束发达的肌肉,连结到腹侧的扇鳍[11][20]。前肠和后肠比中肠来的大,中肠狭窄且生有六对憩室(消化腺)[9][20][24]。真节肢动物的大脑分成三部分,有爪动物的大脑分成二部分,而放射齿目的大脑只有一个部分,位于眼节。前附肢的神经着生于大脑的前侧,复眼的神经着生于大脑的两侧[11][15]。大脑的后侧有一对未愈合的神经节,通过颈部向躯体延伸[11]。

生存年代

[编辑]放射齿目的化石主要产地在中国、美国、加拿大、波兰、澳大利亚、摩洛哥等地的寒武纪地层,其年代与最早的真节肢动物化石年代,都晚于目前已知最古老的三叶虫化石,暗示了其间存在化石证据断层[25]。

-

早寒武皮托虾的前附肢化石保存样貌

1975年,卡齐米拉·伦兹翁(Kazimiera Lendzion)发表了一块来自波兰中东部的扎维申地层(Zawiszyn Formation)的化石,化石年代属于较早的寒武世第三期,比澄江化石地的年代还早。当时此化石被误认为三叶虫,1977年才确定是放射齿目的物种,认定为早寒武皮托虾。2009年,学者们发表在早泥盆世(布拉格期至埃姆斯期)的洪斯吕克板岩生物群中发现了巴氏大鳍盔虾,并将其划入放射齿目,将已知放射齿目的生存年代往后延续了约1亿年[26]。2011年5月,人们在摩洛哥奥陶纪地层发现了新的放射齿目化石[27]。2015年,这批化石被证实属放射齿目并命名为“本莫拉海神盔虾”。

生态学

[编辑]生理学

[编辑]放射齿目被认为是在海底生活的生物,且具有游泳能力,从形态上来看,放射齿目可能经常游动。根据肌肉发达且彼此重叠的腹部扇鳍推测,放射齿目可以通过扇鳍游泳,其运动方式可能呈波浪状,类似现生𫚉鱼和墨鱼[28]。背侧的扇鳍或有些物种中的尾扇则可以改变行进的方向,或在游泳时稳定自身[12][26]。根据奇虾属的尾扇推测,奇虾可以在水中快速转向[29]。刚毛叶带有皱褶的针状结构,可以扩大面积,学者推测其可能是鳃,用来交换氧气以供呼吸[12][20]。

有时候脱落骨化结构(如前附肢和头甲复合结构)会大量聚集,学者推测放射齿目可能会群聚在一起蜕皮[8][12],其他寒武世的节肢动物(如三叶虫)也有群聚蜕皮的行为[30]。

食性

[编辑]

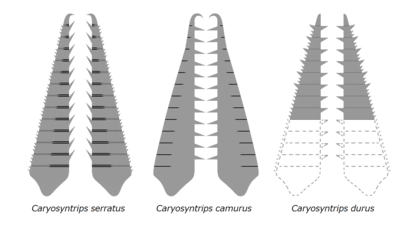

放射齿目的物种具有多样化的觅食策略,包括掠食、筛食底泥或滤食[7][31]。掠食者包括奇虾与抱怪虫,会利用前附肢去攫取猎物,抱怪虫的前附肢甚至长有粗壮的内叶可以像螯那样钳住猎物[6][17][21],较小的头甲及较大的关节膜让这些掠食性放射齿目物种的前附肢更为灵活[23]。底泥筛食者如赫德虾与皮托虾具有较厚实的前附肢,附肢内叶为锯齿状并向身体中轴弯曲,形成类似筛子的结构可以将底泥中的食物碎屑滤出并推向口锥[8],其他放射齿目则有不同针对食底泥的进化适应,例如寒武耙虾就具有圆顶状的 H 骨片,外型类似鲎的头胸甲[8]。滤食者如筛虾属与海神盔虾属(Aegirocassis) 其前附肢的内叶具有密集排列的柔韧辅助棘,可以过滤出体型最小仅 0.5 mm 的浮游动物及浮游植物[13][12]。胡桃夹子虫属(Caryosyntrips) 具有和其他放射齿目相异的前附肢,其内叶为向内相对,类似于剪刀,可用于攫取或切断猎物[17][32]。

-

纳氏皮托虾是滤食底泥的赫德虾科,前附肢粗大且靠近口锥,其口锥为四向辐射对称。

-

北方筛虾的前附肢。筛虾行滤食,前附肢棘较长,且具有紧密的前附肢辅棘。

-

胡桃夹子虫属物种的前附肢,图中可见两前附肢朝向彼此。

根据口器形态,学者推测放射齿目可能以吸吮或啃咬的方式进食,或两者并行[8][18][31],和前附肢一样,不同形态的口器也暗示著放射齿目的食性多样化。如奇虾属的口器为三向辐射对称,齿不规则且凹凸不均,口器开口较小,这些特征暗示著奇虾属以小型且活动力强的猎物为食[31]。赫德虾属和寒武耙虾属的口器开口较大,且齿数较多,暗示着它们可能以较大的食物为食[8][31]。

分类

[编辑]系统发生学

[编辑]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 放射齿目和其他蜕皮动物分类的系统发生树[33] |

多数分析显示,放射齿目是节肢动物门的基群[7][8][13][10][11][12],且为次足类(Deuteropoda) 的姊妹群,次足类包含一些较后期的基群(如抚仙湖虫目、金臂虫目)和真节肢动物(如类肢纲、螯肢亚门和有颚亚门[33])。许多放射齿目生物上类似节肢动物的特征支持了以上假说,这些特征包含复眼[19]、消化腺[24]、前附肢的分节[8][33]、躯体背侧和腹侧的附肢(后来进化成节肢动物的足[8][12])、被外表皮覆盖的前肠及后肠[20],和第一大脑前侧的骨片[34]。隘缩的颈部和咀嚼式结构后来可能进化成节肢动物的头部,其复杂的头部是由数个体节愈合而来[6][15]。

放射齿目和真节肢动物的基群为厌恶虫属(Pambdelurion)、宣扬爪虫属(Kerygmachela)和欧巴宾海蝎属,以上三属是一类形似放射齿目的恐虾纲生物,常被称作“带鳃的叶足动物[12][33]”。带鳃的叶足动物具有扇鳍、消化腺和如同放射齿目一般特化的前附肢,但带鳃的叶足动物的前附肢没有分节,且其扇鳍腹侧生有叶足[12]。欧巴宾海蝎属具有类似放射齿目的眼柄和复眼、尾扇、刚毛叶,和类似真节肢动物位于后侧的嘴[33]。比带鳃的叶足动物更基群的是大网虫属(Megadictyon) 和尖山叶足虫属(Jianshanopodia)[33], 以上两属是叶足动物,生有发达的前附肢和消化道,但没有扇鳍,其形态介于“叶足动物”与“放射齿目和真节肢动物”之间,暗示著全部的节肢动物可能由并系的叶足动物进化而来,全部的节肢动物包含泛节肢动物的缓步动物门和有爪动物门[15]。

旧时研究不认为放射齿目是节肢动物的基群,而认为其为通过趋同进化而来的环神经动物(此假说乃是根据放射齿目与环神经动物相似的环状口器[35]);经比较放射齿目的前附肢、大附肢纲的大附肢和螯肢亚门的螯肢后,学者认为螯肢亚门与大附肢纲为姊妹群[36];曾有学者认为具有接近真节肢动物特征的巴氏大鳍盔虾(Schinderhannes bartelsi)属于赫德虾科[7][8][13][12][33],且是最接近真节肢动物的放射齿目[26],但后来的研究既不支持该种为赫德虾科,也不支持该种最接近真节肢动物。环状排列的口器并非环神经动物特有的,而是经过趋同进化而来,也可能是或为蜕皮动物的祖征(因其同时也在泛节肢动物的缓步动物门与部分有爪动物门中出现[37])。学者认为大附肢纲的大附肢和第二大脑有关[38][39],因此和放射齿目中和第一大脑有关的前附肢非同源[11][15]。仅在一具大鳍盔虾化石上所发现的真节肢动物特征有待商榷,其化石可能具有其他类似放射齿目的特征[33]。

内部分类

[编辑]以前,放射齿目包括恐虾纲下所有的种类,放射齿目中的所有种类又归到一个科里——奇虾科[10][21],因此即使后来该类群重新分类了,“奇虾”一词仍偶尔作为俗称用来指代整个放射齿目[11][12]。基群的恐虾科厌恶虫属、宣扬爪虫属和欧巴宾海蝎属最近从放射齿目中被移除[7][8][13][12],大多数的放射齿目物种被重新分为三个科:抱怪虫科、筛虾科(Tamisiocarididae)[7][8],和赫德虾科。加上奇虾科,这四个现行的放射齿目的科可能组成了进化支奇虾亚目[13]。

放射齿目最初描述时包括奇虾属、Laggania(后来改称皮托虾属)、赫德虾属、Proboscicaris、抱怪虫属、瓜肢虫属和似皮托虾属[4]。但现在,Proboscicaris被视为赫德虾属的同物异名,似皮托虾属则被重新分入大附肢纲[10][12][20]。瓜肢虫属在放射齿目中的位置并不明确,因为该属未被拿来进行支序发生学研究[8],其与放射齿目和真节肢动物的支序发生树呈多分歧状,且还未被厘清[12]。

如果将瓜肢虫属包含在放射齿目中,瓜肢虫属与胡桃夹子虫属是放射齿目中最基群的类群。不过这两个类群现在一般不认为属于奇虾类。抱怪虫科内的关系尚未厘清,常有学者质疑里拉虫属和兰氏虾属是否属于抱怪虫科[5][8]。赫德虾科的多样性较高,多个共演征支持其为单系群的假说,其共演征包含前附肢的端节共有 5 节,且前附肢棘形态几乎相同[8][16],很多研究认为筛虾科为赫德虾科的姊妹群[7][8][13][12]。

- †放射齿目 Radiodonta

- †奇虾亚目 Anomalocarida

- †似奇虾属 Paranomalocaris[40](一些研究将其归入奇虾科[23])

- †刃刺虾属 Laminacaris(一些研究将其归入抱怪虫科[7])

- †奇美拉刃刺虾 L. chimera

- 开拓虾属 Innovatiocaris[42]

- †帽天山开拓虾 I.maotianshanensis

- †多刺开拓虾 I.? multispiniformis

- †奇虾科 Anomalocarididae

- †抱怪虫科 Amplectobeluidae

- †筛虾科 Tamisiocarididae(旧称鲸虾科 Cetiocaridae)

- †赫德虾科 Hurdiidae

- †海神盔虾属 Aegirocassis

- †本莫拉海神盔虾 A. benmoulai

- †皮托虾属 Peytoia

- †纳氏皮托虾 P. nathorsti

- †早寒武皮托虾 P. infercambriensis

- †大鳍盔虾属 Schinderhannes

- †巴氏大鳍盔虾 S. bartelsi

- †斯坦利虾属 Stanleycaris

- †耙肢斯坦利虾 S. hirpex

- †清江斯坦利虾 S. qingjiangensis[43]

- †赫德虾属 Hurdia

- †维多利亚赫德虾 H. victoria

- †三角赫德虾 H. triangulata

- †巨盔虾属 Titanokorys

- †盖氏巨盔虾 T. gainesi

- †小熊虾属 Ursulinacaris

- †高棘小熊虾 U. grallae

- †帕凡特虾属 Pahvantia

- †矛刺帕凡特虾 P. hastata

- †伪窄齿虾属 Pseudoangustidontus

- †双排刺伪窄齿虾 P.duplospineus

- †筛滤伪窄齿虾 P. izdigua

- †寒武耙虾属 Cambroraster

- †镰刺寒武耙虾 C. falcatus

- †心虾属 Cordaticaris

- †线纹心虾 C. striatus

- †口刺虾属 Buccaspinea[44]

- †库氏口刺虾 B. cooperi

- †海神盔虾属 Aegirocassis

- †奇虾亚目 Anomalocarida

Vinther 等人在 2014 年对放射齿目进行了深入的谱系学分析,同年稍晚丛培允等人添加了有爪里拉琴虫对研究进行了扩充[11]。 Van Roy 等人于 2015 年对此进一步研究,并加入了优美瓜状肢虫(Cucumericrus decoratus) 和本莫拉海神盔虾[12]。

|

†奇虾科 Anomalocarididae |

不再属于放射齿目的类群

[编辑]

由于发现的化石样本稀少,有些生物曾被错误地归入放射齿目之下:

- 人们目前只发现了全牙虫的一些牙齿化石。1994年,这些化石被认为是放射齿目动物的口锥[52],到了2006年时人们认定其为一个新属,将其归为鳃曳动物[51]。雅各·温瑟尔(Jakob Vinther)等人于2016年的一份研究中指出,厌恶虫的口器与全牙虫极为相似[53]。

发现史

[编辑]放射齿目的化石在欧、亚、非、北美等大洲,以及澳洲等地皆有发现[58]。

大多放射齿目的表皮柔软,由于身体只有部分骨化,尸体和蜕壳很容易散掉[59]。因此完整的全身化石十分罕见,研究者有时会把不完整的放射齿目化石误认作其他生物,或把多种放射齿目误认为一种。通常,研究人员只能找到前附肢、口器、甲壳、扇鳍等,其中前附肢的化石能提供大量有用信息,有不少类群的建立是基于前附肢化石的发现之上[60][4]。

-

加拿大奇虾的前附肢化石。以前常被认作叶虾类的腹部。

-

同属放射齿目的动物的近乎完整化石(包含前附肢)。

加拿大奇虾和纳氏皮托虾是这方面的典型案例,二者最早发掘出来的都只有不完整的局部化石。其中,前者起初只是发现了前附肢,但研究人员当时误认为是某种虾子的腹部,也因此给它取名为“奇异的虾子”[24]。目前所发现的加拿大奇虾化石都只有腹部,头部的化石则至今仍无下落。后者的口器化石则被误认为是一种水母,并被命名为纳氏皮托虾(Peytoia nathorsti)。而纳氏皮托虾的胴体被误认为是一种海绵或是海参,被命名为 Laggania cambria[61]。最初这些化石并不认为互相有任何关联,一直到了1980年代挖掘到了完整的放射齿目物种化石,才理解到原本化石复原上的错误。在这之后科学家陆续发表了数个放射齿目的属与种,将前附肢的细节、尾鳍的有无、口器牙齿的配置等物种差异区别开来[62]。此外,由于大多化石的发现并不完整,部分被认为属于某物种的化石之后被发现其实属于其他物种,著名的例子包括有些奇虾的牙齿化石,在之后被发现其实是皮托虾的牙齿[63]、以及赫德虾的头部骨片化石被发现其实属于帕凡特虾[5]。

依照惯例,学名必须使用并沿用第一次公布的名称,因此即使“奇异的虾子(Anomalocaris)”最早是针对前附肢化石错误复原的命名,但仍然沿用至今作为奇虾的正式学名。而依据口器牙齿化石命名的模式种皮托虾(Peytoia)被视为是模式种,而 Laggania 则被视为是异名[63]。

参考资料

[编辑]- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 朱茂炎, 赵方臣, 殷宗军, 曾晗, 李国祥. 中国的寒武纪大爆发研究: 进展与展望. 中国科学: 地球科学. 2019, 49 (10): 1455–1490 [2020-05-02]. ISSN 1674-7240. doi:10.1360/SSTe-2019-0183. (原始内容存档于2020-01-07).

- ^ 2.0 2.1 丛培允, 侯先光. 澄江动物群奇虾动物的分异度. 中国古生物学会第十次全国会员代表大会暨第25届学术年会——纪念中国古生物学会成立80周年论文摘要集. 中国古生物学会. 2009.

- ^ Pates, Stephen; Daley, Allison C.; Butterfield, Nicholas J. First report of paired ventral endites in a hurdiid radiodont. dx.doi.org. 2019-06-12 [2023-10-09].

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Collins, Desmond. The "evolution" of Anomalocaris and its classification in the arthropod class Dinocarida (nov.) and order Radiodonta (nov.). Journal of Paleontology. 1996, 70 (2): 280–293. doi:10.1017/S0022336000023362.

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Cong, Pei-Yun; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Daley, Allison C.; Guo, Jin; Pates, Stephen; Hou, Xian-Guang. New radiodonts with gnathobase-like structures from the Cambrian Chengjiang biota and implications for the systematics of Radiodonta. Papers in Palaeontology. 2018, 4 (4): 605–621. ISSN 2056-2802. doi:10.1002/spp2.1219 (英语).

- ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 Cong, Peiyun; Daley, Allison C.; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Hou, Xianguang. The functional head of the Cambrian radiodontan (stem-group Euarthropoda) Amplectobelua symbrachiata. BMC Evolutionary Biology. 2017, 17 (1): 208. ISSN 1471-2148. PMC 5577670

. PMID 28854872. doi:10.1186/s12862-017-1049-1.

. PMID 28854872. doi:10.1186/s12862-017-1049-1.

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Lerosey-Aubril, Rudy; Pates, Stephen. New suspension-feeding radiodont suggests evolution of microplanktivory in Cambrian macronekton. Nature Communications. 2018-09-14, 9 (1): 3774. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6138677

. PMID 30218075. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06229-7 (英语).

. PMID 30218075. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-06229-7 (英语).

- ^ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 8.12 8.13 8.14 8.15 8.16 8.17 8.18 8.19 8.20 8.21 8.22 8.23 8.24 8.25 8.26 8.27 8.28 8.29 8.30 Moysiuk, J.; Caron, J.-B. A new hurdiid radiodont from the Burgess Shale evinces the exploitation of Cambrian infaunal food sources. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2019, 286 (1908): 20191079. PMC 6710600

. PMID 31362637. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.1079.

. PMID 31362637. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.1079.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Cong, Peiyun; Daley, Allison C.; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Hou, Xianguang; Chen, Ailin. Morphology of the radiodontan Lyrarapax from the early Cambrian Chengjiang biota. Journal of Paleontology. 2016, 90 (4): 663–671. ISSN 0022-3360. doi:10.1017/jpa.2016.67 (英语).

- ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 Daley, Allison C.; Budd, Graham E.; Caron, Jean-Bernard; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Collins, Desmond. The Burgess Shale anomalocaridid Hurdia and its significance for early euarthropod evolution. Science. 2009, 323 (5921): 1597–1600. PMID 19299617. doi:10.1126/science.1169514.

- ^ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 11.8 Cong, Peiyun; Ma, Xiaoya; Hou, Xianguang; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Strausfeld, Nicholas J. Brain structure resolves the segmental affinity of anomalocaridid appendages. Nature. 2014, 513 (7519): 538–42. PMID 25043032. doi:10.1038/nature13486.

- ^ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 12.14 12.15 12.16 12.17 12.18 12.19 12.20 12.21 12.22 12.23 Van Roy, Peter; Daley, Allison C.; Briggs, Derek E. G. Anomalocaridid trunk limb homology revealed by a giant filter-feeder with paired flaps. Nature. 2015, 522 (7554): 77–80. PMID 25762145. doi:10.1038/nature14256.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Vinther, Jakob; Stein, Martin; Longrich, Nicholas R.; Harper, David A. T. A suspension-feeding anomalocarid from the Early Cambrian (PDF). Nature. 2014, 507 (7493): 496–499 [2020-05-30]. PMID 24670770. doi:10.1038/nature13010. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2021-01-22).

- ^ 14.0 14.1 Liu, Jianni; Lerosey-Aubril, Rudy; Steiner, Michael; Dunlop, Jason A.; Shu, Degan; Paterson, John R. Origin of raptorial feeding in juvenile euarthropods revealed by a Cambrian radiodontan. National Science Review. 2018-11-01, 5 (6): 863–869. ISSN 2095-5138. doi:10.1093/nsr/nwy057 (英语).

- ^ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5 15.6 Ortega-Hernández, Javier; Janssen, Ralf; Budd, Graham E. Origin and evolution of the panarthropod head – A palaeobiological and developmental perspective. Arthropod Structure & Development. Evolution of Segmentation. 2017-05-01, 46 (3): 354–379. ISSN 1467-8039. PMID 27989966. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2016.10.011.

- ^ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Pates, Stephen; Daley, Allison C.; Butterfield, Nicholas J. First report of paired ventral endites in a hurdiid radiodont. Zoological Letters. 2019-06-11, 5 (1): 18. ISSN 2056-306X. PMC 6560863

. PMID 31210962. doi:10.1186/s40851-019-0132-4.

. PMID 31210962. doi:10.1186/s40851-019-0132-4.

- ^ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Daley, Allison C.; Budd, Graham E. New anomalocaridid appendages from the Burgess Shale, Canada. Palaeontology. 2010, 53 (4): 721–738. ISSN 1475-4983. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2010.00955.x (英语).

- ^ 18.0 18.1 Daley, Allison C.; Bergström, Jan. The oral cone of Anomalocaris is not a classic peytoia. Naturwissenschaften. April 2012, 99 (6): 501–504. ISSN 0028-1042. PMID 22476406. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0910-8 (英语).

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Strausfeld, Nicholas J.; Ma, Xiaoya; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Fortey, Richard A.; Land, Michael F.; Liu, Yu; Cong, Peiyun; Hou, Xianguang. Arthropod eyes: The early Cambrian fossil record and divergent evolution of visual systems. Arthropod Structure & Development. August 2015, 45 (2): 152–172. PMID 26276096. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2015.07.005 (英语).

- ^ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 20.6 20.7 Daley, Allison C.; Edgecombe, Gregory D. Morphology of Anomalocaris canadensis from the Burgess Shale. Journal of Paleontology. 2014, 88 (1): 68–91. doi:10.1666/13-067.

- ^ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Xian‐Guang, Hou; Bergström, Jan; Ahlberg, Per. Anomalocaris and other large animals in the lower Cambrian Chengjiang fauna of southwest China. GFF. September 1995, 117 (3): 163–183. ISSN 1103-5897. doi:10.1080/11035899509546213 (英语).

- ^ Van Roy, Peter; Daley, Allison C.; Briggs, Derek E. G. Anomalocaridids had two sets of lateral flaps. 57th Annual Meeting of The Paleontological Association. Zurich, Switzerland. 2013.

- ^ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Liu, Jianni; Lerosey-Aubril, Rudy; Steiner, Michael; Dunlop, Jason A.; Shu, Degan; Paterson, John R. Origin of raptorial feeding in juvenile euarthropods revealed by a Cambrian radiodontan. National Science Review. 2018-11-01, 5 (6): 863–869. ISSN 2095-5138. doi:10.1093/nsr/nwy057 (英语).

- ^ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Vannier, Jean; Liu, Jianni; Lerosey-Aubril, Rudy; Vinther, Jakob; Daley, Allison C. Sophisticated digestive systems in early arthropods. Nature Communications. 2014-05-02, 5 (1): 3641. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 24785191. doi:10.1038/ncomms4641 (英语).

- ^ Daley, Allison; Antcliffe, Jonathan; Drage, Harriet; Pates, Stephen. Early fossil record of Euarthropoda and the Cambrian Explosion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2018-05-21, 115: 201719962 [2020-06-22]. doi:10.1073/pnas.1719962115. (原始内容存档于2020-06-25).

- ^ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Kühl, Gabriele; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Rust, Jes. A Great-Appendage Arthropod with a Radial Mouth from the Lower Devonian Hunsrück Slate, Germany. Science. 2009-02-06, 323 (5915): 771–773. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19197061. doi:10.1126/science.1166586 (英语).

- ^ Van Roy, Peter; Briggs, Derek E. G. A giant Ordovician anomalocaridid. Nature. 2011-05, 473 (7348): 510–513 [2020-06-22]. ISSN 0028-0836. doi:10.1038/nature09920. (原始内容存档于2021-02-24) (英语).

- ^ Usami, Yoshiyuki. Theoretical study on the body form and swimming pattern of Anomalocaris based on hydrodynamic simulation. Journal of Theoretical Biology. 2006-01-07, 238 (1): 11–17. ISSN 0022-5193. PMID 16002096. doi:10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.05.008.

- ^ Sheppard, K. A.; Rival, D. E.; Caron, J.-B. On the Hydrodynamics of Anomalocaris Tail Fins. Integrative and Comparative Biology. 2018-10-01, 58 (4): 703–711. ISSN 1540-7063. PMID 29697774. doi:10.1093/icb/icy014 (英语).

- ^ Daley, Allison; Drage, Harriet. The fossil record of ecdysis, and trends in the moulting behaviour of trilobites. Arthropod Structure & Development. 2015-09-01, 45 (2): 71–96. PMID 26431634. doi:10.1016/j.asd.2015.09.004.

- ^ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 De Vivo, Giacinto; Lautenschlager, Stephan; Vinther, Jakob. Reconstructing anomalocaridid feeding appendage dexterity sheds light on radiodontan ecology. 2016-12-16.

- ^ Pates, S.; Daley, A. C. Caryosyntrips: a radiodontan from the Cambrian of Spain, USA and Canada. Papers in Palaeontology. 2017, 3 (3): 461–470 [2020-05-30]. ISSN 2056-2802. doi:10.1002/spp2.1084. (原始内容存档于2019-12-24) (英语).

- ^ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 33.7 33.8 Ortega-Hernández, Javier. Making sense of 'lower' and 'upper' stem-group Euarthropoda, with comments on the strict use of the name Arthropoda von Siebold, 1848. Biological Reviews of the Cambridge Philosophical Society. Dec 2014, 91 (1): 255–273. ISSN 1469-185X. PMID 25528950. doi:10.1111/brv.12168.

- ^ Ortega-Hernández, Javier. Homology of Head Sclerites in Burgess Shale Euarthropods. Current Biology. 2015-06-15, 25 (12): 1625–1631. ISSN 0960-9822. PMID 25959966. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.034.

- ^ Xian‐Guang, Hou; Bergström, Jan; Ahlberg, Per. Anomalocaris and other large animals in the lower Cambrian Chengjiang fauna of southwest China. GFF. September 1995, 117 (3): 163–183. ISSN 1103-5897. doi:10.1080/11035899509546213 (英语).

- ^ Haug, Joachim T.; Waloszek, Dieter; Maas, Andreas; Liu, Yu; Haug, Carolin. Functional morphology, ontogeny and evolution of mantis shrimp-like predators in the Cambrian: MANTIS SHRIMP-LIKE CAMBRIAN PREDATORS. Palaeontology. March 2012, 55 (2): 369–399. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2011.01124.x (英语).

- ^ Smith, Martin R.; Caron, Jean-Bernard. Hallucigenia 's head and the pharyngeal armature of early ecdysozoans. Nature. June 2015, 523 (7558): 75–78. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 26106857. doi:10.1038/nature14573 (英语).

- ^ Tanaka, Gengo; Hou, Xianguang; Ma, Xiaoya; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Strausfeld, Nicholas J. Chelicerate neural ground pattern in a Cambrian great appendage arthropod. Nature. October 2013, 502 (7471): 364–367. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 24132294. doi:10.1038/nature12520 (英语).

- ^ Ortega-Hernández, Javier; Lerosey-Aubril, Rudy; Pates, Stephen. Proclivity of nervous system preservation in Cambrian Burgess Shale-type deposits. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2019-12-18, 286 (1917): 20192370. PMC 6939931

. PMID 31822253. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.2370.

. PMID 31822253. doi:10.1098/rspb.2019.2370.

- ^ 40.0 40.1 Wang, YuanYuan; Huang, DiYing; Hu, ShiXue. New anomalocardid frontal appendages from the Guanshan biota, eastern Yunnan. Chinese Science Bulletin. 2013-06-07, 58 (32). ISSN 1001-6538. doi:10.1007/s11434-013-5908-x.

- ^ Jiao, De-guang; Pates, Stephen; Lerosey-Aubril, Rudy; Ortega-Hernandez, Javier; Yang, Jie; Lan, Tian; Zhang, Xi-guang. The endemic radiodonts of the Cambrian Stage 4 Guanshan biota of South China. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 2021, 66 [2024-06-17]. ISSN 0567-7920. doi:10.4202/app.00870.2020. (原始内容存档于2023-04-20).

- ^ Zeng, Han; Zhao, Fangchen; Zhu, Maoyan. Innovatiocaris, a complete radiodont from the early Cambrian Chengjiang Lagerstätte and its implications for the phylogeny of Radiodonta. Journal of the Geological Society. 2022-09-07. ISSN 0016-7649. doi:10.1144/jgs2021-164.

- ^ Wu, Yu; Pates, Stephen; Zhang, Mingjing; Lin, Weiliang; Ma, Jiaxin; Liu, Cong; Wu, Yuheng; Zhang, Xingliang; Fu, Dongjing. Exceptionally preserved radiodont arthropods from the lower Cambrian (Stage 3) Qingjiang Lagerstätte of Hubei, South China and the biogeographic and diversification patterns of radiodonts. Papers in Palaeontology. 2024-07, 10 (4). ISSN 2056-2799. doi:10.1002/spp2.1583.

- ^ Pates, Stephen; Lerosey-Aubril, Rudy; Daley, Allison C.; Kier, Carlo; Bonino, Enrico; Ortega-Hernández, Javier. The diverse radiodont fauna from the Marjum Formation of Utah, USA (Cambrian: Drumian). PeerJ. 2021-01-19, 9: e10509 [2021-03-19]. ISSN 2167-8359. doi:10.7717/peerj.10509. (原始内容存档于2021-02-01) (英语).

- ^ Xian‐Guang, Hou; Bergström, Jan; Ahlberg, Per. Anomalocaris and Other Large Animals in the Lower Cambrian Chengjiang Fauna of Southwest China. GFF. 1995-09-01, 117: 163–183 [2020-06-15]. doi:10.1080/11035899509546213. (原始内容存档于2018-07-22).

- ^ STEIN, MARTIN. A new arthropod from the Early Cambrian of North Greenland, with a ‘great appendage’-like antennula. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 2010-02-26, 158 (3): 477–500 [2020-06-15]. ISSN 0024-4082. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00562.x. (原始内容存档于2019-11-03) (英语).

- ^ Legg, David. Multi-Segmented Arthropods from the Middle Cambrian of British Columbia (Canada). Journal of Paleontology. 2013-05-01, 87: 493–501 [2020-06-15]. doi:10.1666/12-112.1. (原始内容存档于2018-09-18).

- ^ C., Daley, Allison; D., Edgecombe, Gregory. Morphology of Anomalocaris canadensis from the Burgess Shale. Journal of Paleontology. [2020-06-15]. ISSN 0022-3360. (原始内容存档于2019-10-27) (英语).

- ^ Van Roy, Peter; Daley, Allison C.; Briggs, Derek E. G. Anomalocaridid trunk limb homology revealed by a giant filter-feeder with paired flaps. Nature. 2015, 522 (7554): 77–80. ISSN 0028-0836. PMID 25762145. doi:10.1038/nature14256.

- ^ The Cambrian fossils of Chengjiang, China : the flowering of early animal life. Hou, Xianguang. Second edition. Chichester, West Sussex. ISBN 9781118896310. OCLC 970396735.

- ^ 51.0 51.1 Xianguang, Hou; Bergström, Jan; Jie, Yang. Distinguishing anomalocaridids from arthropods and priapulids. Geological Journal. 2006, 41 (3-4): 259–269 [2020-06-15]. ISSN 1099-1034. doi:10.1002/gj.1050. (原始内容存档于2021-02-25) (德语).

- ^ Chen, Jun-yuan; Ramsköld, Lars; Zhou, Gui-qing. Evidence for Monophyly and Arthropod Affinity of Cambrian Giant Predators. Science. 1994-05-27, 264 (5163): 1304–1308 [2020-06-15]. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 17780848. doi:10.1126/science.264.5163.1304. (原始内容存档于2021-02-25) (英语).

- ^ Vinther, Jakob; Porras, Luis; Young, Fletcher; Budd, Graham; Edgecombe, Gregory. The mouth apparatus of the Cambrian gilled lobopodian Pambdelurion whittingtoni. Palaeontology. 2016-09-01 [2020-06-15]. doi:10.1111/pala.12256. (原始内容存档于2018-06-12).

- ^ Zeng, Han; Zhao, Fangchen; Yin, Zongjun; Zhu, Maoyan. Morphology of diverse radiodontan head sclerites from the early Cambrian Chengjiang Lagerstätte, south-west China. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 2017-01-04, 16: 1 [2020-06-15]. doi:10.1080/14772019.2016.1263685. (原始内容存档于2018-06-21).

- ^ Anomalocaridids and the origin of arthropods: the view from Chengjiang. ResearchGate. [2019-01-19]. (原始内容存档于2019-04-17) (英语).

- ^ Guo, Jin; Pates, Stephen; Cong, Peiyun; Daley, Allison; Edgecombe, Gregory; Chen, Taimin; Hou, Xianguang. A new radiodont (stem Euarthropoda) frontal appendage with a mosaic of characters from the Cambrian (Series 2 Stage 3) Chengjiang biota. Papers in Palaeontology. 2018-08-17 [2020-06-15]. doi:10.1002/spp2.1231. (原始内容存档于2018-09-17).

- ^ Cong, Pei-Yun; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Daley, Allison C.; Guo, Jin; Pates, Stephen; Hou, Xian-Guang. New radiodonts with gnathobase-like structures from the Cambrian Chengjiang biota and implications for the systematics of Radiodonta. Papers in Palaeontology. 2018-06-23 [2020-06-15]. ISSN 2056-2802. doi:10.1002/spp2.1219. (原始内容存档于2019-05-31) (英语).

- ^ Pates, S.; Botting, J. P.; McCobb, L. M. E.; Muir, L. A. A miniature Ordovician hurdiid from Wales demonstrates the adaptability of Radiodonta. Royal Society Open Science. 2020, 7 (6): 200459 [2020-06-13]. ISSN 2054-5703. doi:10.1098/rsos.200459. (原始内容存档于2021-06-03).

- ^ Daley, Allison C.; Budd, Graham E.; Caron, Jean-Bernard; Edgecombe, Gregory D.; Collins, Desmond. The Burgess Shale Anomalocaridid Hurdia and Its Significance for Early Euarthropod Evolution. Science. 2009-03-20, 323 (5921): 1597–1600 [2020-06-22]. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 19299617. doi:10.1126/science.1169514. (原始内容存档于2021-02-26) (英语).

- ^ Pates, Stephen; Daley, Allison C. The Kinzers Formation (Pennsylvania, USA): the most diverse assemblage of Cambrian Stage 4 radiodonts. Geological Magazine. 2019, 156 (7): 1233–1246 [2020-07-05]. ISSN 0016-7568. doi:10.1017/S0016756818000547 (英语).

- ^ Jay,, Gould, Stephen. Wonderful life : the Burgess Shale and the nature of history First edition. New York. [2020-06-22]. ISBN 0393027058. OCLC 18983518. (原始内容存档于2021-02-17).

- ^ Whittington, Harry Blackmore; Briggs, Derek Ernest Gilmor. The largest Cambrian animal, Anomalocaris, Burgess Shale, British-Columbia. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. 1985-05-14, 309 (1141): 569–609 [2020-06-22]. ISSN 0080-4622. doi:10.1098/rstb.1985.0096. (原始内容存档于2018-10-08) (英语).

- ^ 63.0 63.1 Daley, Allison; Bergström, Jan. The oral cone of Anomalocaris is not a classic ‘‘peytoia’’. Die Naturwissenschaften. 2012-04-05, 99: 501–4 [2020-06-22]. doi:10.1007/s00114-012-0910-8. (原始内容存档于2018-09-18).