解析几何

| 几何学 |

|---|

|

| 几何学家 |

|

|

解析几何(英语:Analytic geometry),又称为坐标几何(英语:Coordinate geometry)或卡氏几何(英语:Cartesian geometry),早先被叫作笛卡尔几何,是一种借助于解析式进行图形研究的几何学分支。解析几何通常使用二维的平面直角坐标系研究直线、圆、圆锥曲线、摆线、星形线等各种一般平面曲线,使用三维的空间直角坐标系来研究平面、球等各种一般空间曲面,同时研究它们的方程,并定义一些图形的概念和参数。

在中学课本中,解析几何被简单地解释为:采用数值的方法来定义几何形状,并从中提取数值的信息。然而,这种数值的输出可能是一个方程或者是一种几何形状。

1637年,笛卡尔在《方法论》的附录“几何”中提出了解析几何的基本方法。 以哲学观点写成的这部法语著作为后来牛顿和莱布尼茨各自提出微积分学提供了基础。

对代数几何学者来说,解析几何也指(实或者复)流形,或者更广义地通过一些复变量(或实变量)的解析函数为零而定义的解析空间理论。这一理论非常接近代数几何,特别是通过让-皮埃尔·塞尔在《代数几何和解析几何》领域的工作。这是一个比代数几何更大的领域,不过也可以使用类似的方法。

历史

[编辑]古希腊数学家梅内克缪斯(Menaechmus)的解题、证明方式与现在使用坐标系十分相似,以至于有时会认为他是解析几何的鼻祖。[1] 阿波罗尼奥斯在《论切触》中解题方式在现在被称之为单维解析几何;他使用直线来求得一点与其它点之间的比例。[2]阿波罗尼奥斯在《圆锥曲线论》中进一步发展了这种方式,这种方式与解析几何十分相似,比起笛卡儿早了1800多年。他使用了参照线、直径、切线与现今所使用坐标系没有本质区别,即从切点沿直径所量的距离为横坐标,而与切线平行、并与数轴和曲线向交的线段为纵坐标。他进一步发展了横坐标与纵坐标之间的关系,即两者等同于夸张的曲线。然而,阿波罗尼奥斯的工作接近于解析几何,但他没能完成它,因为他没有将负数纳入系统当中。在此,方程是由曲线来确定的,而曲线不是由方程得出的。坐标、变量、方程不过是一些给定几何题的脚注罢了。[3]

十一世纪波斯帝国数学家欧玛尔·海亚姆发现了几何与代数之间的密切联系,在求三次方程使用了代数和几何,取得了巨大进步。[4][5]但最关键的一步由笛卡儿完成。[4]

从传统意义上讲,解析几何是由勒内·笛卡儿创立的。[4][6][7]笛卡儿的创举被记录在《几何学》(La Geometrie)当中,在1637年与他的《方法论》一道发表。这些努力是以法语写成的,其中的哲学思想为创立无穷小演算提供了基础。最初,这些著作并没有得到认可,部分原因是由于其中论述的间断,方程的复杂所致。直到1649年,著作被翻译为拉丁语,并被冯·斯霍滕(van Schooten)恭维后,才被大众所认可接受。[8]

费马也为解析几何的发展做出了贡献。他的《平面与立体轨迹引论》(Ad locos planos et solidos isagoge)虽然没有在生前发表,但手稿于1637年在巴黎出现,正好早于笛卡儿《方法论》一点。[9]《引论》文字清晰,获得好评,为解析几何提供了铺垫。费马与笛卡儿方法的不同在于出发点。费马从代数公式开始,然后描述它的几何曲线,而笛卡儿从几何曲线开始,以方程的完结告终。[8]结果,笛卡儿的方法可以处理更复杂的方程,并发展到使用高次多项式来解决问题。

基本理论

[编辑]

坐标

[编辑]在解析几何当中,平面给出了坐标系,即每个点都有对应的一对实数坐标。最常见的是笛卡儿坐标系,其中,每个点都有坐标对应水平位置,和坐标对应垂直位置。这些常写为有序对。这种系统也可以被用在三维几何当中,空间中的每个点都以多元组呈现。

坐标系也以其它形式出现。在平面中最常见的另类坐标系是极坐标系,其中每个点都以从原点出发的半径和角度表示。在三维空间中,最常见的另类坐标系统是圆柱坐标系和 球坐标系。

曲线方程

[编辑]在解析几何当中,任何方程都包含确定面的子集,即方程的解集。例如,方程在平面上对应的是所有坐标等于坐标的解集。这些点汇集成为一条直线,被称为这道方程的直线。总而言之,线性方程中和定义线,一元二次方程定义圆锥曲线,更复杂的方程则阐述更复杂的形象。

通常,一个简单的方程对应平面上的一条曲线。但这不一定如此:方程对应整个平面,方程只对应一点。在三维空间中,一个方程通常对应一个曲面,而曲线常常代表两个曲面的交集,或一条参数方程。方程代表了是半径为r且圆心在上的所有圆。

距离和角度

[编辑]在解析几何当中,距离、角度等几何概念是用公式来表达的。这些定义与背后的欧几里得几何所蕴含的主旨相符。例如,使用平面笛卡儿坐标系时,两点和之间的距离 (又写作,被定义为

上述可被认为是一种勾股定理的形式。类似地,直线与水平线所成的角可以定义为

其中是线的斜率。

变化

[编辑]

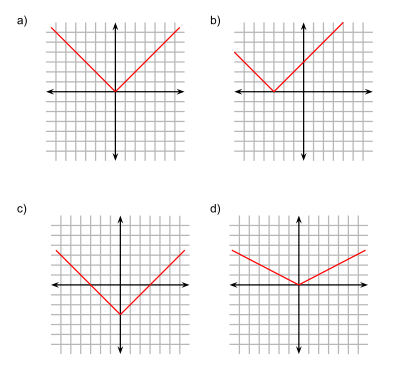

变化可以使母方程变为新方程,但保持原有的特性。例如,母方程 有水平和垂直的渐近线,处在第一和第三象限当中能够,它所有的变形都有水平和垂直的渐近线,出现在第一或第三、第二或第四象限当中。总的来说,如果,那么它可以变为。新的变形方程, 因素如果大于1,就垂直拉伸方程;如果小于1,就压缩方程。如果 值为负,那么方程就反映在 -轴上。 值如果大于1就水平压缩方程,小于1就拉伸方程。与一样,如果为负就反映在-轴上。 和 值为平移,值是垂直, 为水平。 和 的正值意味着方程往数轴的正方向移动,负值意味这往数轴的负方向移动。

变化可以应用到任意几何等式中,不论等式是否代表某一方程。 变化可以被认为是个体处理、或是组合处理。

例如, 在 平面上指代单位圆。 图像可以被变化为:

- 将变为 ,使得图像向右移动个单位。

- 将变为,使得图像向上移动个单位。

- 将变为,使得图像以值拉伸。 (想象一下 被膨胀了)

- 将变为,使得图像垂直拉伸。

- 将变为,将 变为 ,使得图像旋转 个角度。

在基础的解析几何中,不会考虑太多的变化,例如偏移。更多信息请参阅仿射变换。

交集

[编辑]虽然本讨论仅限于平面上,但它可以很容易地衍生为更高维的空间中。两个几何对象和指代和,其交集是所有点的集合。 例如,可以是半径为1的圆,圆心在: , 可以是半径为1的圆,圆心在。两圆的交叉点是满足方程的所有点的集合。点是否满足方程呢?将带入,便成为或,结论为真,因此在上。换句话来说,接着将带入,方程 成为 或 ,结论为假。 不在 上,因此不是它的集合。

与 的交集可以通过同时解方程来求得:

解得

我们的交集有两点:

就圆锥曲线而言,交集可能会出现至多4个点。

截距

[编辑]被广泛研究的一种交集是几何对象与和坐标轴的交集。

几何对象与 轴的交集被称之为对象的 截距。与轴的交集被称之为对象的截距。

就线 而言,参数定义线在何处与轴相交。据此,或点被称之为截距。

主题

[编辑]解析几何中的重要问题:

. 如果被考虑进去的话,就会常常用到旋转。这些问题常涉及到线性代数。

例子

[编辑]下面是美国初中数学竞赛(USMTS)中的题,可以用解析几何来解:

问题:在凸面五边形中,边长为 , , , , ,虽然顺序不一定如此。设, , , 成为 , , , 的各个中点。 设 为线段 的中点, 为线段 的中点。线段 的长度为整数。求边 的所有可能长度。

解: 为了不失一般性,假设 , , , , 为 , , , , 。

应用中点公式,点 , , , , , 位于

- , , , , ,

使用距离公式,

以及

由于 为整数,

(见同余) 因此 .

现代解析几何

[编辑]解析簇(analytic variety)定义为几个解析函数的共同解集。类似与实数与复数的代数簇。任何复流形都是一种解析簇。由于解析簇可能有奇点,但不是所有解析簇都是复数。.

解析几何总体上来说等同与实数与复数代数几何,让-皮埃尔·塞尔在他的著作《代数几何与解析几何》(Géometrie Algébrique et Géométrie Analytique)阐述了这个观点。然而,两个领域依然有其独特性,而证明方式也十分不同,代数几何也包括几何的有限特征。

注释

[编辑]- ^ Boyer, Carl B. The Age of Plato and Aristotle. A History of Mathematics Second Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1991: 94–95. ISBN 0-471-54397-7.

Menaechmus apparently derived these properties of the conic sections and others as well. Since this material has a strong resemblance to the use of coordinates, as illustrated above, it has sometimes been maintained that Menaechmus had analytic geometry. Such a judgment is warranted only in part, for certainly Menaechmus was unaware that any equation in two unknown quantities determines a curve. In fact, the general concept of an equation in unknown quantities was alien to Greek thought. It was shortcomings in algebraic notations that, more than anything else, operated against the Greek achievement of a full-fledged coordinate geometry.

- ^ Boyer, Carl B. Apollonius of Perga. A History of Mathematics Second Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1991: 142. ISBN 0-471-54397-7.

The Apollonian treatise On Determinate Section dealt with what might be called an analytic geometry of one dimension. It considered the following general problem, using the typical Greek algebraic analysis in geometric form: Given four points A, B, C, D on a straight line, determine a fifth point P on it such that the rectangle on AP and CP is in a given ratio to the rectangle on BP and DP. Here, too, the problem reduces easily to the solution of a quadratic; and, as in other cases, Apollonius treated the question exhaustively, including the limits of possibility and the number of solutions.

- ^ Boyer, Carl B. Apollonius of Perga. A History of Mathematics Second Edition. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1991: 156. ISBN 0-471-54397-7.

The method of Apollonius in the Conics in many respects are so similar to the modern approach that his work sometimes is judged to be an analytic geometry anticipating that of Descartes by 1800 years. The application of references lines in general, and of a diameter and a tangent at its extremity in particular, is, of course, not essentially different from the use of a coordinate frame, whether rectangular or, more generally, oblique. Distances measured along the diameter from the point of tangency are the abscissas, and segments parallel to the tangent and intercepted between the axis and the curve are the ordinates. The Apollonian relationship between these abscissas and the corresponding ordinates are nothing more nor less than rhetorical forms of the equations of the curves. However, Greek geometric algebra did not provide for negative magnitudes; moreover, the coordinate system was in every case superimposed a posteriori upon a given curve in order to study its properties. There appear to be no cases in ancient geometry in which a coordinate frame of reference was laid down a priori for purposes of graphical representation of an equation or relationship, whether symbolically or rhetorically expressed. Of Greek geometry we may say that equations are determined by curves, but not that curves are determined by equations. Coordinates, variables, and equations were subsidiary notions derived from a specific geometric situation; [...] That Apollonius, the greatest geometer of antiquity, failed to develop analytic geometry, was probably the result of a poverty of curves rather than of thought. General methods are not necessary when problems concern always one of a limited number of particular cases.

- ^ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Boyer. The Arabic Hegemony. 1991: 241–242.

Omar Khayyam (ca. 1050–1123), the "tent-maker," wrote an Algebra that went beyond that of al-Khwarizmi to include equations of third degree. Like his Arab predecessors, Omar Khayyam provided for quadratic equations both arithmetic and geometric solutions; for general cubic equations, he believed (mistakenly, as the sixteenth century later showed), arithmetic solutions were impossible; hence he gave only geometric solutions. The scheme of using intersecting conics to solve cubics had been used earlier by Menaechmus, Archimedes, and Alhazan, but Omar Khayyam took the praiseworthy step of generalizing the method to cover all third-degree equations (having positive roots). .. For equations of higher degree than three, Omar Khayyam evidently did not envision similar geometric methods, for space does not contain more than three dimensions, ... One of the most fruitful contributions of Arabic eclecticism was the tendency to close the gap between numerical and geometric algebra. The decisive step in this direction came much later with Descartes, but Omar Khayyam was moving in this direction when he wrote, "Whoever thinks algebra is a trick in obtaining unknowns has thought it in vain. No attention should be paid to the fact that algebra and geometry are different in appearance. Algebras are geometric facts which are proved."

缺少或|title=为空 (帮助) - ^ Glen M. Cooper (2003). "Omar Khayyam, the Mathematician", The Journal of the American Oriental Society 123.

- ^ Stillwell, John. Analytic Geometry. Mathematics and its History Second Edition. Springer Science + Business Media Inc. 2004: 105. ISBN 0-387-95336-1.

the two founders of analytic geometry, Fermat and Descartes, were both strongly influenced by these developments.

- ^ Cooke, Roger. The Calculus. The History of Mathematics: A Brief Course. Wiley-Interscience. 1997: 326. ISBN 0-471-18082-3.

The person who is popularly credited with being the discoverer of analytic geometry was the philosopher René Descartes (1596–1650), one of the most influential thinkers of the modern era.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 Katz 1998,pg. 442

- ^ Katz 1998,pg. 436

引述

[编辑]著作

[编辑]- Katz, Victor J., A History of Mathematics: An Introduction (2nd Ed.), Reading: Addison Wesley Longman, 1998, ISBN 0-321-01618-1

- Boyer, Carl B., History of Analytic Geometry, Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0486438320

- Cajori, Florian, A History of Mathematics, AMS, ISBN 978-0821821022

- Struik, D. J., A Source Book in Mathematics, 1200-1800, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674823556

文献

[编辑]- Boyer, Carl B. Analytic Geometry: The Discovery of Fermat and Descartes, Mathematics Teacher 37, no. 3 (1944): 99-105

- Boyer, Carl B., Johann Hudde and space coordinates

- Bissell, C. C., Cartesian geometry: The Dutch contribution

- Pecl, J., Newton and analytic geometry

- Coolidge, J. L., The Beginnings of Analytic Geometry in Three Dimensions

外部链接

[编辑]- Coordinate Geometry topics (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) with interactive animations

![{\displaystyle y=af[b(x-k)]+h}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/0f34caab00b2cedd33661cbd66c097371f05abbf)