黏菌素

| |

| |

| 临床资料 | |

|---|---|

| 商品名 | Xylistin、Coly-Mycin M、Colobreathe及其他 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682860 |

| 核准状况 | |

| 给药途径 | 外用药物, 口服给药, 静脉注射, 肌肉注射, 吸入 |

| ATC码 | |

| 法律规范状态 | |

| 法律规范 |

|

| 药物动力学数据 | |

| 生物利用度 | 0% |

| 生物半衰期 | 5小时 |

| 识别信息 | |

| |

| CAS号 | 1066-17-7 8068-28-8 |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII |

|

| KEGG | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.012.644 |

| 化学信息 | |

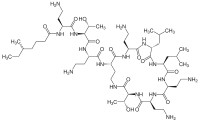

| 化学式 | C52H98N16O13 |

| 摩尔质量 | 1,155.46 g·mol−1 |

| 3D模型(JSmol) | |

| |

| |

黏菌素(INN:colistin,也称为多黏菌素 E,英语:polymyxin E)是一种抗生素,作为治疗包含肺炎在内的多重抗药性革兰氏阴性菌感染的最后手段。[7][8]这类感染与绿脓杆菌、肺炎克雷伯氏菌或不动杆菌属等病原细菌有关联。[9]黏菌素有两种形式:黏菌素甲磺酸钠,经由静脉注射、肌肉注射或由患者吸入给药,而硫酸黏菌素则主要涂抹在皮肤上(外用药物)或是口服给药。[10]黏菌素甲磺酸钠[11]是一种前体药物 - 经由化学反应,将黏菌素分子上的特定部分(伯胺)接上一个叫做磺甲基的化学基团而制成。黏菌素甲磺酸钠在非经肠道途径给药时,其毒性会低于黏菌素。[11]黏菌素甲磺酸钠在水溶液中会水解,形成部分硫甲基化衍生物以及黏菌素的复杂混合物。[11]

世界部分地区自2015年起已开始有对黏菌素的抗药性出现。[12]

使用注射形式的黏菌素常见的副作用有肾脏问题和神经系统问题。[8]其他严重的副作用有过敏性休克、肌肉无力和艰难拟梭菌感染相关性腹泻。[8]吸入形式制剂可能导致支气管收缩。[8]目前尚不清楚个体于怀孕期间使用对胎儿是否安全。[13]黏菌素属于多黏菌素类药物。[8]它的作用是分解细胞膜,通常会导致细菌死亡。[8]

黏菌素于1947年被发现,黏菌素甲磺酸钠于1970年在美国获得批准用于医疗用途。[9][8]它已列入世界卫生组织基本药物标准清单之中。[14]世界卫生组织(WHO)将黏菌素归类为对人类医学不可或缺的药物。[15]市场上有其通用名药物流通。[16]此药物由类芽孢杆菌属中萃取而来。[10]

医疗用途

[编辑]抗菌谱

[编辑]黏菌素在治疗由假单胞菌属、埃希氏菌属和克雷伯氏菌属菌种引起的感染方面有效。以下是代表一些具有医学意义的微生物最小抑菌浓度 (MIC) 敏感性数据:[17][18]

- 大肠杆菌:0.12–128微克/毫升

- 肺炎克雷伯氏菌:0.25–128微克/毫升

- 绿脓杆菌:≤0.06–16微克/毫升

给药和剂量

[编辑]剂型

[编辑]市售黏菌素药物有两种形式:硫酸黏菌素和黏菌素甲磺酸钠。硫酸黏菌素是阳离子,而黏菌素甲磺酸钠是阴离子。硫酸黏菌素稳定,而黏菌素甲磺酸钠则容易水解成多种甲磺酸化衍生物。硫酸黏菌素和黏菌素甲磺酸钠通过不同的途径从用药者体内排出。对绿脓杆菌而言,黏菌素甲磺酸钠是黏菌素的无活性前药。硫酸黏菌素和黏菌素甲磺酸两者不可互换使用。

剂量

[编辑]硫酸黏菌素和黏菌素甲磺酸钠都可经由静脉注射给药,但剂量计算很复杂。研究人员Li等人[19]注意到世界不同地区,在黏菌素甲磺酸钠非经肠道途径给药产品的标签指示并不相同。

由于黏菌素在50多年前就已引入临床应用,因此它从未受到现代药物所受的法规约束,而黏菌素的剂量也并没标准化,也没关于药理学或药物动力学的详细试验。因此,对于大多数感染,黏菌素的最佳剂量仍然未知。

抗药性

[编辑]对黏菌素的抗药性很罕见,但已有相关描述。截至2017年,科学界对如何定义黏菌素抗药性尚未达成共识。法国微生物学会采2毫克/升的最小抑菌浓度临界值,而英国抗菌化学治疗学会则将4毫克/升或更低的最小抑菌浓度临界值设定为敏感,8毫克/升或更高设定为抗药性。美国则没提出描述黏菌素敏感性的标准。

第一个已知的黏菌素抗药性基因存在质体中,可在细菌菌株之间传播,此基因被称为MCR-1。MCR-1于2011年在中国一个经常使用黏菌素的养猪场被发现,并在2015年11月公诸于世。[20][21]自2015年12月起,在东南亚、数个欧洲国家[22]和美国[23]均陆续证实这种质体基因的存在。

首个详细的黏菌素抗药性研究报告在印度发表,该研究记录并分析18个月内出现的13例黏菌素抗药性感染病例。研究结论指出,泛耐药性感染,尤其是血液感染,具有更高的死亡率。其他印度医院也报告多起病例。[24][25]对多黏菌素的抗药性出现通常低于10%,但在地中海和东南亚/东亚(韩国和新加坡)更为常见,这些地区的黏菌素抗药性案例数目正在上升。[26]美国于2016年5月发现对黏菌素具有抗药性的大肠杆菌。[27]

并非所有对黏菌素和其他一些抗生素的抗药性都是由于抗药性基因存在所导致。[28]异质性抗药性是指表观上基因相同的微生物,对某种抗生素表现出不同程度的抗药性现象。[29]这种现象最晚从2016年起已在某些肠杆菌属细菌中观察到,[28]并在2017-2018年于某些肺炎克雷伯氏菌菌株中发现。[30]在某些情况下,这种现象会产生严重的临床后果。[30]

不良反应

[编辑]静脉注射发生的主要毒性是肾毒性和神经毒性,[31][32][33][34]但这可能是给药的剂量非常高 - 远高于目前制造商推荐的,并且没针对患者已有的肾脏疾病作调整。神经毒性和肾毒性作用似乎是暂时性,停药或减少剂量后会消退。[35]

每8小时经静脉注射160毫克黏菌素甲磺酸钠的剂量,很少发生肾毒性。[36][37]事实上,黏菌素似乎比后来取代它的胺基糖苷类抗生素毒性更小,且连续使用长达6个月也并未有不良影响。[38]低白蛋白血症患者尤其容易出现黏菌素引起的肾毒性。[39]

气雾剂(吸入式)治疗发生的主要毒性是支气管痉挛,[40]可使用β2-肾上腺素受体激动剂(如沙丁胺醇)[41]或按照脱敏疗程进行治疗或预防。[42]

作用机制

[编辑]黏菌素是一种聚阳离子肽,同时具有亲水性和亲脂性官能基。[43]

黏菌素与革兰氏阴性菌外细胞膜中的脂多糖和磷脂结合。它与膜脂质磷酸基团竞争性地取代二价阳离子(Ca2+和Mg2+),导致外细胞膜破坏、细胞内物质泄漏,继而死亡。

药物动力学

[编辑]胃肠道中不会发生具有临床意义的黏菌素吸收,因此对于全身性感染,必须经由注射黏菌素给药。黏菌素甲磺酸酯经由肾脏消除,但黏菌素则通过尚未明确的非肾脏机制消除。[44][45]

历史

[编辑]黏菌素最初于1949年由日本微生物学家Y. Koyama(小山康夫)在日本从一瓶发酵的多黏芽孢杆菌变种黏菌素(Bacillus polymyxa var. colistinus)中分离而来,[46]并于1959年开始用于临床应用。[47]

黏菌素甲磺酸钠是一种毒性较低的黏菌素前药,于1959年开始作注射剂使用。由于此药物具有肾毒性和神经毒性,因此其使用在1980年代受到广泛停止。虽然黏菌素具有毒性,但随着多重抗药性细菌在1990年代日益普遍,它开始作为一种迫不得已的应急方案,而受到重新审视。[48]

黏菌素也曾用于畜牧业,尤其是在1980年代以后的中国。中国在此类的黏菌素于2015年的产量超过2,700吨。但在2016年开始禁止在畜牧业中使用黏菌素作为生长促进剂。[49]

生物合成

[编辑]生物合成黏菌素需用到三种氨基酸:苏胺酸、白胺酸和2,4-二胺基丁酸。

参见

[编辑]- ^ Drug Product Database. Health Canada. 2012-04-25 [2022-01-13].

- ^ Colobreathe 1,662,500 IU inhalation powder, Hard Capsules – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). (emc). [2020-11-16].

- ^ Colomycin 1 million International Units (IU) Powder for solution for injection, infusion or inhalation – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). (emc). 2020-05-27 [16 November 2020].

- ^ Promixin 1 million International Units (IU) Powder for Nebuliser Solution – Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC). (emc). 2020-09-23 [2020-11-16].

- ^ Coly-Mycin M- colistimethate injection. DailyMed. 3 December 2018 [2020-11-16].

- ^ Colobreathe EPAR. European Medicines Agency. 2018-09-17 [12020-11-16].

- ^ Pogue JM, Ortwine JK, Kaye KS. Clinical considerations for optimal use of the polymyxins: A focus on agent selection and dosing. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. April 2017, 23 (4): 229–233. PMID 28238870. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.02.023

.

.

- ^ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Colistimethate Sodium Monograph for Professionals. Drugs.com. [2019-11-06].

- ^ 9.0 9.1 Falagas ME, Grammatikos AP, Michalopoulos A. Potential of old-generation antibiotics to address current need for new antibiotics. Expert Review of Anti-Infective Therapy. October 2008, 6 (5): 593–600. PMID 18847400. S2CID 13158593. doi:10.1586/14787210.6.5.593.

- ^ 10.0 10.1 Bennett JE, Dolin R, Blaser MJ, Mandell GL. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett's Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2009: 469. ISBN 9781437720600.

- ^ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Bergen PJ, Li J, Rayner CR, Nation RL. Colistin methanesulfonate is an inactive prodrug of colistin against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. June 2006, 50 (6): 1953–1958. PMC 1479097

. PMID 16723551. doi:10.1128/AAC.00035-06.

. PMID 16723551. doi:10.1128/AAC.00035-06.

- ^ Hasman H, Hammerum AM, Hansen F, Hendriksen RS, Olesen B, Agersø Y, et al. Detection of mcr-1 encoding plasmid-mediated colistin-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from human bloodstream infection and imported chicken meat, Denmark 2015. Euro Surveillance. 2015-12-10, 20 (49): 30085. PMID 26676364. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2015.20.49.30085

.

.

- ^ Colistimethate (Coly Mycin M) Use During Pregnancy. Drugs.com. [2019-11-11].

- ^ World Health Organization. World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2019. hdl:10665/325771

. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ World Health Organization. Critically important antimicrobials for human medicine 6th revision. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2019. ISBN 9789241515528. hdl:10665/312266

.

.

- ^ British national formulary : BNF 76 76. Pharmaceutical Press. 2018: 547. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ Polymyxin E (Colistin) – The Antimicrobial Index Knowledgebase – TOKU-E. [2016-05-25]. (原始内容存档于2016-05-28).

- ^ Colistin sulfate, USP Susceptibility and Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Data (PDF). 2016-03-03 [2014-02-10]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2016-03-04).

- ^ Li J, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Milne RW, Coulthard K, Rayner CR, Paterson DL. Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. September 2006, 6 (9): 589–601. PMID 16931410. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(06)70580-1.

- ^ Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, Yi LX, Zhang R, Spencer J, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study. The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. February 2016, 16 (2): 161–168. PMID 26603172. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7.

- ^ Zhang S. Resistance to the Antibiotic of Last Resort Is Silently Spreading. The Atlantic. [2017-01-12]. (原始内容存档于2017-01-13).

- ^ McKenna M. Apocalypse Pig Redux: Last-Resort Resistance in Europe. Phenomena. 2015-12-03 [2016-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2016-05-28).

- ^ First discovery in United States of colistin resistance in a human E. coli infection. www.sciencedaily.com. [2016-05-27]. (原始内容存档于2016-05-27).

- ^ Emergence of Pan drug resistance amongst gram negative bacteria! The First case series from India. December 2014.

- ^ New worry: Resistance to 'last antibiotic' surfaces in India. The Times of India. 2014-12-28. (原始内容存档于2014-12-31).

- ^ Bialvaei AZ, Samadi Kafil H. Colistin, mechanisms and prevalence of resistance. Current Medical Research and Opinion. April 2015, 31 (4): 707–721. PMID 25697677. S2CID 33476061. doi:10.1185/03007995.2015.1018989

.

.

- ^ Discovery of first mcr-1 gene in E. coli bacteria found in a human in United States. cdc.gov. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 2016-05-31 [2016-07-06]. (原始内容存档于2016-07-11).

- ^ 28.0 28.1 McKay B. Common 'Superbug' Found to Disguise Resistance to Potent Antibiotic. wsj.com. Wall Street Journal. 2018-03-06 [2018-11-01]. (原始内容存档于2018-04-03).

- ^ El-Halfawy OM, Valvano MA. Antimicrobial heteroresistance: an emerging field in need of clarity. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. January 2015, 28 (1): 191–207. PMC 4284305

. PMID 25567227. doi:10.1128/CMR.00058-14.

. PMID 25567227. doi:10.1128/CMR.00058-14.

- ^ 30.0 30.1 Band VI, Satola SW, Burd EM, Farley MM, Jacob JT, Weiss DS. Carbapenem-Resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae Exhibiting Clinically Undetected Colistin Heteroresistance Leads to Treatment Failure in a Murine Model of Infection. mBio. March 2018, 9 (2): e02448–17. PMC 5844991

. PMID 29511071. doi:10.1128/mBio.02448-17.

. PMID 29511071. doi:10.1128/mBio.02448-17.

- ^ Wolinsky E, Hines JD. Neurotoxic and nephrotoxic effects of colistin in patients with renal disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. April 1962, 266 (15): 759–762. PMID 14008070. doi:10.1056/NEJM196204122661505.

- ^ Koch-Weser J, Sidel VW, Federman EB, Kanarek P, Finer DC, Eaton AE. Adverse effects of sodium colistimethate. Manifestations and specific reaction rates during 317 courses of therapy. Annals of Internal Medicine. June 1970, 72 (6): 857–868. PMID 5448745. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-72-6-857.

- ^ Ledson MJ, Gallagher MJ, Cowperthwaite C, Convery RP, Walshaw MJ. Four years' experience of intravenous colomycin in an adult cystic fibrosis unit. The European Respiratory Journal. September 1998, 12 (3): 592–594. PMID 9762785. doi:10.1183/09031936.98.12030592

.

.

- ^ Li J, Nation RL, Milne RW, Turnidge JD, Coulthard K. Evaluation of colistin as an agent against multi-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents. January 2005, 25 (1): 11–25. PMID 15620821. doi:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2004.10.001.

- ^ Beringer P. The clinical use of colistin in patients with cystic fibrosis. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. November 2001, 7 (6): 434–440. PMID 11706322. S2CID 38084953. doi:10.1097/00063198-200111000-00013.

- ^ Conway SP, Etherington C, Munday J, Goldman MH, Strong JJ, Wootton M. Safety and tolerability of bolus intravenous colistin in acute respiratory exacerbations in adults with cystic fibrosis. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. November 2000, 34 (11): 1238–1242. PMID 11098334. S2CID 42625124. doi:10.1345/aph.19370.

- ^ Littlewood JM, Koch C, Lambert PA, Høiby N, Elborn JS, Conway SP, et al. A ten year review of colomycin. Respiratory Medicine. July 2000, 94 (7): 632–640. PMID 10926333. doi:10.1053/rmed.2000.0834

.

.

- ^ Stein A, Raoult D. Colistin: an antimicrobial for the 21st century?. Clinical Infectious Diseases. October 2002, 35 (7): 901–902. PMID 12228836. doi:10.1086/342570

.

.

- ^ Beringer P. The clinical use of colistin in patients with cystic fibrosis. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. November 2001, 7 (6): 434–440. PMID 11706322. S2CID 38084953. doi:10.1097/00063198-200111000-00013.

- ^ Maddison J, Dodd M, Webb AK. Nebulized colistin causes chest tightness in adults with cystic fibrosis. Respiratory Medicine. February 1994, 88 (2): 145–147. PMID 8146414. doi:10.1016/0954-6111(94)90028-0

.

.

- ^ Kamin W, Schwabe A, Krämer I. Inhalation solutions: which one are allowed to be mixed? Physico-chemical compatibility of drug solutions in nebulizers. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis. December 2006, 5 (4): 205–213. PMID 16678502. doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2006.03.007

.

.

- ^ Domínguez-Ortega J, Manteiga E, Abad-Schilling C, Juretzcke MA, Sánchez-Rubio J, Kindelan C. Induced tolerance to nebulized colistin after severe reaction to the drug. Journal of Investigational Allergology & Clinical Immunology. 2007, 17 (1): 59–61. PMID 17323867.

- ^ Li J, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Milne RW, Coulthard K, Rayner CR, Paterson DL. Colistin: the re-emerging antibiotic for multidrug-resistant Gram-negative bacterial infections. The Lancet. Infectious Diseases. September 2006, 6 (9): 589–601. PMID 16931410. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70580-1.

- ^ Li J, Milne RW, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Smeaton TC, Coulthard K. Pharmacokinetics of colistin methanesulphonate and colistin in rats following an intravenous dose of colistin methanesulphonate. The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. May 2004, 53 (5): 837–840. PMID 15044428. doi:10.1093/jac/dkh167

.

.

- ^ Li J, Milne RW, Nation RL, Turnidge JD, Smeaton TC, Coulthard K. Use of high-performance liquid chromatography to study the pharmacokinetics of colistin sulfate in rats following intravenous administration. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. May 2003, 47 (5): 1766–1770. PMC 153303

. PMID 12709357. doi:10.1128/AAC.47.5.1766-1770.2003.

. PMID 12709357. doi:10.1128/AAC.47.5.1766-1770.2003.

- ^ Koyama Y, Kurosasa A, Tsuchiya A, Takakuta K. A new antibiotic 'colistin' produced by spore-forming soil bacteria. J Antibiot (Tokyo). 1950, 3.

- ^ MacLaren G, Spelman D. Hopper DC, Hall KK , 编. Colistin: An overview. UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer. 2022-11-22 [2016-06-06]. (原始内容存档于2016-05-31).

- ^ Falagas ME, Kasiakou SK. Colistin: the revival of polymyxins for the management of multidrug-resistant gram-negative bacterial infections. Clinical Infectious Diseases. May 2005, 40 (9): 1333–1341. PMID 15825037. S2CID 21679015. doi:10.1086/429323

.

.

- ^ Schoenmakers K. How China is getting its farmers to kick their antibiotics habit. Nature. 2020-10-21 [2021-08-02].

延伸阅读

[编辑]- Reardon S. Spread of antibiotic-resistance gene does not spell bacterial apocalypse — yet. Nature. December 2015. doi:10.1038/nature.2015.19037

.

.

外部链接

[编辑]- Colistin topics page (bibliography). Science.gov.