埃里温汗国

埃里温汗国 خانات ایروان | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1747年—1828年 | |||||||||

埃里温汗国疆域(米黄色部分,约1800年) | |||||||||

| 首都 | 埃里温 | ||||||||

| 常用语言 | 波斯语(官方语言)、阿塞拜疆语、库尔德语、亚美尼亚语 | ||||||||

| 族群 | 突厥人、波斯人、库尔德人、亚美尼亚人 | ||||||||

| 宗教 | 伊斯兰教什叶派 | ||||||||

| 政府 | 汗国 | ||||||||

| 汗 | |||||||||

• 1747年-1752年 | 米尔梅赫迪汗(首任) | ||||||||

• 1807年-1828年 | 侯赛因·汗·萨达尔(末任) | ||||||||

| 历史 | |||||||||

• 建立 | 1747年 | ||||||||

• 终结 | 1828年 | ||||||||

| 面积 | |||||||||

• 总计 | 19,500平方公里 | ||||||||

| 人口 | |||||||||

• 1826年估计 | 110120人 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

埃里温汗国(波斯语:خانات ایروان;亚美尼亚语:Երևանի խանություն;阿塞拜疆语:İrəvan xanlığı),是1747年建立于高加索地区的汗国,为波斯附庸的高加索诸汗国之一,以波斯语为官方语言;疆域约为19,500平方公里[2],包含今日亚美尼亚中部、土耳其厄德尔省和卡尔斯省的卡厄兹曼以及阿塞拜疆纳希切万自治共和国的沙鲁尔区和萨达拉克区,国内居民以穆斯林为主,包括突厥人、波斯人与库尔德人,另有约两成为信仰基督教的亚美尼亚人,其社群受埃里温梅利克直接管理[2]。

埃里温汗国的首都为今日亚美尼亚的首都埃里温,是波斯在多次俄罗斯-波斯战争中对抗俄罗斯帝国的防御中心[2],侯赛因·汗·萨达尔治下的埃里温相当繁荣,全城有居民近2万人,埃里温蓝色清真寺即为汗国的代表建筑。1827年,波斯在最后一次俄罗斯-波斯战争中战败,埃里温汗国被俄罗斯占领[3],并于隔年的《土库曼斯坦恰伊条约》中被割让给俄罗斯,后者将埃里温汗国与纳希切万汗国的领土合并为亚美尼亚州。

历史

[编辑]埃里温汗国的疆域过去属于萨法维王朝的埃里温省,阿夫沙尔王朝建立后,纳迪尔沙将此地区分为埃里温汗国、纳希切万汗国、卡拉巴赫汗国与占贾汗国[4],埃里温汗国与纳希切万汗国的疆土属于波斯亚美尼亚[5]。纳迪尔沙死后伊朗陷入混乱,埃里温汗国先后成为桑德王朝与卡扎尔王朝的附庸[6],其中后者会派任卡扎尔王室成员作为埃里温汗国的统治者[7][8]。埃里温汗国分为15个区,以波斯语为官方语言[9][10][11],地方官僚为仿照德黑兰中央政府的官僚系统设立[12]。

十九世纪初,俄罗斯帝国并吞了卡尔特利-卡赫蒂王国,1804年发动俄罗斯-波斯战争,埃里温成为波斯抵御俄罗斯的防卫中心[2]。1804年,俄军在帕维尔·齐贾诺夫率领下攻击埃里温,包围埃里温城,后来被卡札尔王朝的储君阿巴斯·米尔札率军击退[2]。1807年,卡札尔王朝沙阿法特赫-阿里沙·卡扎尔任命侯赛因·汗·萨达尔为埃里温汗国统治者(汗)与阿拉斯河以北波斯军队的指挥官(萨达尔)[7][13],侯赛因·汗·萨达尔统治下的埃里温汗国相当繁荣,为卡札尔王朝的模范省[2],他设立有效率的管理体制让当地的亚美尼亚人恢复了对波斯统治的信心[2][12]。

1808年,俄军将领伊万·古多维奇率军袭击埃里温,亦被击退,1813年《古利斯坦条约》签订后,波斯失去了大部分高加索的领土,埃里温与大不里士成为两国攻防的前线[2]。1826年,最后一次俄罗斯-波斯战争爆发[14],战争初期波斯成功夺回许多于1813年失去的领土,但隔年俄罗斯在阿巴薩巴德堡(位于纳希切万汗国)、萨达尔堡(位于埃里温汗国)与埃里温大败波斯军队,于1827年10月2日攻陷埃里温。1828年2月,波斯被迫签订《土库曼斯坦恰伊条约》,将埃里温汗国与其他阿拉斯河以北的领土割让给俄罗斯帝国[2]。

行政区划

[编辑]首府

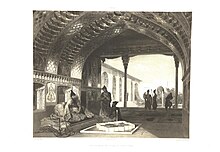

[编辑]卡札尔王朝时期,埃里温汗国治下的埃里温相当繁荣,城市范围约为一平方英里,花园等城郊则延伸到距城市18英里处。Kettenhofen等编纂的伊朗百科全书描述埃里温有3个区,超过1700间房舍、850间商铺、约10座清真寺、7座教堂、10间澡堂、7座商队驿站、5个广场、2处巴刹与2所学校[2]。城内两座最重要的清真寺中,一座建于萨法维时期,另一座(埃里温蓝色清真寺)则是埃里温汗国时期建造,为该时期代表性的建筑之一[16]。侯赛因·汗·萨达尔时期,埃里温的城防据称是波斯全境最坚固的[17],城市的人口稳定增长 在埃里温被俄罗斯攻陷前夕,全城有居民近2万人[18],而俄罗斯统治约70年后,埃里温的人口仅剩约14000人[18][注 1]。

君主列表

[编辑]

- 米尔梅赫迪汗(1747年-1752年)[19]

- 哈利勒·汗·乌兹别克斯坦(1752年-1755年)[20]

- 哈桑纳利汗(1755年-1759年)[21]

- 胡塞纳利汗(1759年-1783年)[22]

- 古拉姆阿里汗(1783年-1784年)[23]

- 穆罕默德汗(1785年-1805年)[24]

- 莫赫迪古鲁汗(1805年-1806年)[25]

- 艾哈迈德·汗·穆卡德姆(1806年)[26]

- 侯赛因·汗·萨达尔(1807年-1828年)

人口

[编辑]埃里温汗国的人口多数为穆斯林,约占八成,另外两成则为信仰基督教的亚美尼亚人[27][注 2]。

| 种族 | 人数 |

|---|---|

| 亚美尼亚人[注 3] | 20,073人 |

| 库尔德人 | 25,237人 |

| 波斯官员、军队[注 4] | 10,000人 |

| 突厥人(定居与半定居)[注 5] | 31,588人 |

| 突厥人(游牧) | 23,222人 |

| 总计 | 110,120人 |

波斯人

[编辑]

埃里温汗国的统治者与部分居民为波斯人[31],不过“波斯人”一词在此语境中常用来表示统治阶级,包括官员与其部属、军人与部分商人等[32],不一定反映种族,因此有时也包含突厥人在内[28]。有些波斯人死于1826-1828年的战争,其余在俄罗斯占领埃里温汗国后几乎全部迁至波斯本土[32]。

突厥人

[编辑]突厥人为埃里温汗国最大的族群,有巴岳特、Ayrumlu、卡扎尔人、卡拉帕帕赫人、白羊土库曼斯坦人、黑羊土库曼斯坦人等部族[33],包括定居、半定居与随季节迁徙的游牧者[31],前者多务农为业[34] ,后者则为汗国提供了重要的马匹来源[35]。有时突厥部族间会发生冲突,传统上也与库尔德人不合[36],突厥人与库尔德人游牧的范围约为汗国疆域的一半,主要位于中北部。卡拉帕帕赫人与Ayrumlu是汗国中主要的两个突厥游牧部族,1828年后他们多在阿巴斯·米尔札帮助下迁至了伊朗阿塞拜疆[37]。

库尔德人

[编辑]库尔德人的生活型态多为游牧,和许多突厥人相似。库尔德人的宗教信仰包括伊斯兰教逊尼派、什叶派与亚兹迪教[38],传统上库尔德人与突厥人不合[36]。

亚美尼亚人

[编辑]亚美尼亚人信仰基督教,在埃里温汗国中约占两成,虽集中在汗国中的数个区域[39],但在各区域均非主要族群[27][注 6]。14世纪中叶以前亚美尼亚人是东亚美尼亚的主要族群[41],随着穆斯林移入和几位统治者的压迫而成为少数族群[42][43]。但埃里温汗国的商业贸易为亚美尼亚人主导[44][2],因此他们对波斯统治者有重要的经济价值,他们虽与俄罗斯人同为基督徒,但对其不抱持特别的好感,而较为关注自己的社会、经济地位[45],例如1808年俄军包围埃里温时,亚美尼亚人即维持中立[46]。

俄罗斯占领埃里温汗国后,波斯官员与军队回到伊朗本土[31],大量亚美尼亚人从土耳其与俄罗斯迁入[44][47],1832年亚美尼亚人人数已与穆斯林相当[27],克里米亚战争与1877年俄土战争后,另一批土耳其亚美尼亚人的移入使亚美尼亚人在此地占稳定多数。不过埃里温直至20世纪仍是以穆斯林为主的城市[40]。

自治

[编辑]埃里温汗国的亚美尼亚人直接受埃里温阿加马利安(Aghamalyan)家族的梅利克管辖。1639年奥斯曼-波斯战争结束后波斯亚美尼亚即开始了梅利克的行政管理系统,1736年纳迪尔沙加冕时,当时的埃里温梅利克哈克布延(Melik Hakobjan)便出席观礼[2]。埃里温梅利克受沙阿授权,可穿著波斯官员的服饰,对其辖下的亚美尼亚人具有完整的行政、立法与司法权,甚至有权判处死刑。此外梅利克还有军事功能,在战争时率领部众参加波斯军队。除埃里温梅利克外,汗国内还有其他地区的梅利克,各自管理当地的亚美尼亚人,不过仍以埃里温梅利克最为重要、最具影响力,几乎仅次于汗本人,汗国内的亚美尼亚村落每年均需向埃里温梅利克缴税[2]。

后世影响

[编辑]

埃里温汗国为波斯附庸,且居民以突厥人为主,在现代阿塞拜疆与亚美尼亚两国的领土争议中,阿塞拜疆经常提起埃里温汗国以强调自己在高加索地区的历史,并削弱亚美尼亚领土主张的正当性。2018年,阿塞拜疆总统伊利哈姆·阿利耶夫演讲时指出埃里温与许多亚美尼亚的领土历史上属于阿塞拜疆人,因此后者应有权返回那些地区,其外交部发言人随后表示阿利耶夫的言论并非领土主张,而是“恢复历史正义”,让阿塞拜疆人能回到那些地方、拿回失去的财产与拜访祖先的墓地[48][49][50]。2020年,在纪念纳哥诺卡拉巴克战争战胜的阅兵游行中,阿利耶夫再次指出埃里温等地在历史上为阿塞拜疆人的土地[51][52]。

现在埃里温除了蓝色清真寺作为“波斯清真寺”被保留之外,包括宫殿在内的其他埃里温汗国建筑皆已不存[48]。

注释

[编辑]参考文献

[编辑]脚注

- ^ Bournoutian, George A. The 1820 Russian Survey of the Khanate of Shirvan: A Primary Source on the Demography and Economy of an Iranian Province prior to its Annexation by Russia. Gibb Memorial Trust. 2016: xvii. ISBN 978-1909724808.

Serious historians and geographers agree that after the fall of the Safavids, and especially from the mid-eighteenth century, the territory of the South Caucasus was composed of the khanates of Ganja, Kuba, Shirvan, Baku, Talesh, Sheki, Karabagh, Nakhichivan and Yerevan, all of which were under Iranian suzerainty.

- ^ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 Kettenhofen, Bournoutian & Hewsen 1998,第542–551页.

- ^ Muriel Atkin. Russia and Iran, 1780-1828 (U of Minnesota Press, 1980), p. 89; "The new khan of Yerevan, Hosein Qoli, was one of the most able men in Fath' Ali's government and ruled Yerevan from 1807 until its conquest by the Russians in 1827."

- ^ Bournoutian 2006,第214–215页.

- ^ Bournoutian 1980,第1–2页.

- ^ Bournoutian 2006,第215页.

- ^ 7.0 7.1 Bournoutian 2002,第215页. "Iranians, in order to save the rest of eastern Armenia, heavily subsidized the region and appointed a capable governor, Hosein Qoli Khan, to administer it."

- ^ Bournoutian 2004,第519–520页.

- ^ Swietochowski, Tadeusz. Russian Azerbaijan, 1905-1920: The Shaping of a National Identity in a Muslim Community. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 2004: 12. ISBN 978-0521522458.

(...) and Persian continued to be the official language of the judiciary and the local administration [even after the abolishment of the khanates].

- ^ Pavlovich, Petrushevsky Ilya. Essays on the history of feudal relations in Armenia and Azerbaijan in XVI - the beginning of XIX centuries. LSU them. Zhdanov. 1949: 7.

(...) The language of official acts not only in Iran proper and its fully dependant Khanates, but also in those Caucasian khanates that were semi-independent until the time of their accession to the Russian Empire, and even for some time after, was New Persian (Farsi). It played the role of the literary language of class feudal lords as well.

- ^ Katouzian, Homa. Iranian history and politics. Routledge. 2003: 128. ISBN 978-0415297547.

Indeed, since the formation of the Ghaznavids state in the tenth century until the fall of Qajars at the beginning of the twentieth century, most parts of the Iranian cultural regions were ruled by Turkic-speaking dynasties most of the time. At the same time, the official language was Persian, the court literature was in Persian, and most of the chancellors, ministers, and mandarins were Persian speakers of the highest learning and ability.

- ^ 12.0 12.1 Bournoutian 1982,第86页. "The Khan Hosein Qoli Khan's efficient administration soon transformed the region. He modeled his bureaucracy on that of the central government, dividing power between tribal and settled groups (...) In essence the Erevan administration, like its counterpart in Tehran, was organized into three branches (...)"

- ^ Bournoutian 2004,第519–520页. "ḤOSAYNQOLI KHAN SARDĀR-E IRAVĀNI; important governor in the early Qajar period (b. ca. 1742, d. 1831). (...) Requiring a strong and loyal governor to command the fortress of Erevan against the Russian advances during the first Russo-Persian War (1804-13), the shah appointed Ḥosaynqoli as the commander-in-chief (sardār) of the Persian forces north of the Araxes (Aras) River."

- ^ Dowling, Timothy C. (编). Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond. ABC-CLIO. 2015: 729. ISBN 978-1598849486.

In May 1826, Russia therefore occupied Mirak, in the Erivan khanate, in violation of the Treaty of Gulistan.

- ^ Шопен И. Исторический памятник состояния Армянской области в эпоху ее присоединения к Российской империи. : 441-448 (俄语).

- ^ Kettenhofen, Bournoutian & Hewsen 1998,第542–551页. "(...) built in 1776 near the end of Persian rule."

- ^ Hambly, Gavin. The traditional Iranian city in the Qājār period. Avery, Peter; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles (编). The Cambridge History of Iran (Vol. 7). Cambridge University Press. 1991: 552. ISBN 978-0521200950.

Erivan was renowned for its strong natural defences and the impressive fortifications maintained by its governor between 1807 and 1827, the famous sardār, Husain Qulī Khan, which were said to be the strongest in the country.

- ^ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Bournoutian 1992,第62页.

- ^ Qarayev 2016,第52页.

- ^ Əliyev & Həsənov 2007,第90页.

- ^ Qarayev 2016,第60页.

- ^ Qarayev 2016,第83-84页.

- ^ Qarayev 2016,第90页.

- ^ Əliyev & Həsənov 2007,第148页.

- ^ Qarayev 2016,第173页.

- ^ A.A.Bakıxanov adına Tarix İnstitutu. İrəvan xanlığı (Rusiya işğalı və ermənilərin Şimali Azərbaycan torpaqlarına köçürülməsi). Regionların inkişafı ictimai birliyi. 2010: 204 (阿塞拜疆语).

- ^ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Bournoutian 1980,第12–13页.

- ^ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Bournoutian 1980,第15页.

- ^ Bournoutian 1980,第12页.

- ^ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Bournoutian 1992,第63页.

- ^ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Bournoutian 1980,第3页.

- ^ 32.0 32.1 Bournoutian 1992,第49页.

- ^ Bournoutian 1980,第4, 15页.

- ^ Bournoutian 1992,第50页.

- ^ Bournoutian 1980,第5–6页.

- ^ 36.0 36.1 Bournoutian 1992,第53页.

- ^ Bournoutian 1992,第53–54页.

- ^ Bournoutian 1992,第54页.

- ^ Bournoutian 1992,第61页.

- ^ 40.0 40.1 Bournoutian 1980,第13页.

- ^ Bournoutian 1980,第11, 13–14页.

- ^ An Ethnohistorical Dictionary of the Russian and Soviet Empires, James S. Olson, Greenwood(1994), p. 44

- ^ An Historical Atlas of Islam by William Charles Brice, Brill Academic Publishers, 1981 p. 276

- ^ 44.0 44.1 Bournoutian 1980,第14页.

- ^ Bournoutian 1992,第91–92页.

- ^ Bournoutian 1992,第83页.

- ^ Bournoutian 1980,第11–13页.

- ^ 48.0 48.1 Austin Clayton. Azerbaijan mounts exhibition showcasing Erivan Khanate. Eurasianet. 2019-10-17 [2020-12-27]. (原始内容存档于2020-11-01).

- ^ Joshua Kucera. Azerbaijan President Calls for Return to “Historic Lands” in Armenia. Eurasianet. 2018-02-13 [2020-12-27]. (原始内容存档于2020-05-10).

- ^ Yerevan Slams Aliyev’s Latest Territorial Claim on Armenia; Calls Azerbaijani President’s Remarks ‘Racist’. The Armenian Weekly. 2018-02-09 [2020-12-27]. (原始内容存档于2020-11-09).

- ^ At Baku Victory Parade, Aliyev Calls Yerevan, Zangezur, Sevan Historical Azerbaijani Lands, Erdogan Praises Enver Pasha. The Armenian Mirror-Spectator. 2020-12-11 [2020-12-12]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-15) (英语).

- ^ Yerevan Condemns 'Azeri Territorial Claims'. Azatutyun. 2020-12-11 [2020-12-12]. (原始内容存档于2020-12-24) (英语).

文献

- Bournoutian, George A. The Population of Persian Armenia Prior to and Immediately Following its Annexation to the Russian Empire: 1826-1832. The Wilson Center, Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies. 1980.

- Bournoutian, George A. Eastern Armenia in the Last Decades of Persian Rule 1807-1828: A Political and Socioeconomic Study of the Khanate of Erevan on the Eve of the Russian Conquest. Undena Publications. 1982: 1–290. ISBN 978-0890031223.

- Bournoutian, George A. The Khanate of Erevan Under Qajar Rule: 1795-1828. Mazda Publishers. 1992: 1–355. ISBN 978-0939214181.

- Bournoutian, George A. A Concise History of the Armenian People: (from Ancient Times to the Present). Mazda Publishers. 2002.

- Bournoutian, George A. ḤOSAYNQOLI KHAN SARDĀR-E IRAVĀNI. Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5: 519–520. 2004.

- Bournoutian, George A. A Concise History of the Armenian People 5. Costa Mesa, California: Mazda Publishers. 2006. ISBN 1-56859-141-1.

- Floor, Willem M. Titles and Emoluments in Safavid Iran: A Third Manual of Safavid Administration, by Mirza Naqi Nasiri. Washington, DC: Mage Publishers. 2008. ISBN 978-1933823232.

- Kettenhofen, Erich; Bournoutian, George A.; Hewsen, Robert H. EREVAN. Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. VIII, Fasc. 5: 542–551. 1998.

- Əliyev, Fuad; Həsənov, Urfan. İrəvan xanlığı. Şərq- Qərb. 2007. ISBN 978-9952-34-166-9 (阿塞拜疆语).

- Qarayev, Elçin. "Azərbaycanın İrəvan bölgəsinin tarixindən(XVII yüzilliyin sonu–XIX yüzilliyin ortalarında)". Mütərcim Tərcümə və Nəşriyyat-Poliqrafiya Mərkəzi. 2016 (阿塞拜疆语).