禁止化学武器公约

| 关于禁止发展、生产、储存和使用化学武器及销毁此种武器的公约 | |

|---|---|

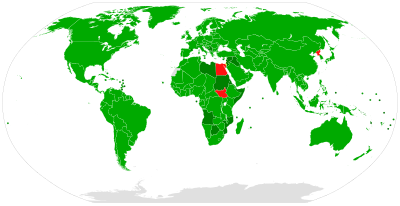

禁止化学武器公约成员国

签署并批准

加入

签署但尚未批准

未签署 | |

| 起草完成日 | 1992年9月3日[1] |

| 签署日 | 1993年1月13日[1] |

| 签署地点 | |

| 生效日 | 1997年4月29日[1] |

| 生效条件 | 65个国家批准[2] |

| 签署者 | 165[1] |

| 缔约方 | 193 (至2018年5月)[1] 缔约国全部名单 4个联合国会员国没有签约或批准:埃及、以色列、北朝鲜、南苏丹 |

| 保存处 | |

| 语言 | 阿拉伯语、汉语、英语、法语、俄语及西班牙语[4] |

| 收录于维基文库的条约原文 | |

| 大规模杀伤性武器 |

|---|

|

| 种类 |

| 政治实体 |

| 散布 |

| 条约 |

《关于禁止发展、生产、储存和使用化学武器及销毁此种武器的公约》(英语:Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on Their Destruction),简称《禁止化学武器公约》(CWC),是由国际组织禁止化学武器组织(OPCW)管理的军备控制条约。条约于1997年4月29日生效。条约不仅禁止使用化学武器,而且还限制大规模的开发、生产、储存以及转移化学武器或前体,除非用于有限目的(研究、医疗、制药)。缔约国的主要义务是实施化武禁令,并销毁所有化学武器。所有销毁化学武器的活动都必须在OPCW的监督下进行。

截至2022年8月,已有193个国家成为《禁止化学武器公约》的缔约国并接受条约义务。以色列已签署但未批准该条约,三个联合国会员国(埃及、朝鲜和南苏丹)既未签署也未加入条约。[5][6]巴勒斯坦国于2018年5月17日交存了其《禁止化学武器公约》的加入文件。2013年9月,叙利亚作为销毁叙利亚化学武器协议的一部分,加入了条约。[7][8]

截至2021年2月,全球已申报的化学武器库存已经被销毁了98.39%。公约包含了对化学生产设施的评估规定,以及基于其它国家的情报对化学武器扩散的指控进行调查的规定。[9]

某些在战争中广泛使用但也有大规模工业用途的化学品(如磷化氢)也会受到严格监管,但也存在一些例外。氯气具有毒性,但作为一种纯元素且主要用于和平目的时,并不被正式列为化学武器。一些国家(例如叙利亚阿萨德政府)继续定期生产和实施这种类型的化学品作为武器。[10]虽然这些化学品不被《禁止化学武器公约》控制,但任何以化学物质毒性为主要或唯一目的的使用都被条约禁止。其它化学品,例如具有毒性的白磷,但它们在军事上的使用是允许的,除非利用其毒性效果。[11][12]

历史

[编辑]《禁止化学武器公约》是对1925年《日内瓦议定书》的补充,后者禁止在国际武装冲突中使用化学武器和生物武器,但不禁止发展或拥有。公约还包括一系列广泛的核查措施,例如现场检查,而1975年的《禁止生物武器公约》缺乏核查制度。[13][14]

经过几次名称和结构的变化,欧洲裁军谈判会议最终于1984年演变为裁军谈判会议。[15]1992年9月3日,裁军大会向联合国大会提交了年度报告,其中包含了公约的文本。联合国大会于1992年11月30日批准了公约,联合国秘书长于1993年1月13日在巴黎开放签署。[16]条约一直开放到1997年4月29日正式生效,即匈牙利向联合国交存了第65个批准文件之后的180天。[17]

禁止化学武器组织(OPCW)

[编辑]

公约由禁止化学武器组织(OPCW)管理,该组织是条约的法律平台。[18]缔约国会改变并制定实施组织条例。组织的技术秘书处会进行检查,确保成员国的遵守情况。检查主要针对销毁设施(在销毁过程中进行永久监控)、已经拆除或民用的化学武器生产设施,以及化学品工业的检查。

2013年诺贝尔和平奖授予了该组织,因为它与公约一起,“将使用化学武器定义为国际法的禁忌”。[19][20]

公约的关键要点

[编辑]- 禁止生产和使用化学武器

- 销毁或监督转换为其它功能的化学武器设施

- 销毁所有化学武器(包括在缔约国领土外遗弃的化学武器)

- 在出现使用化学武器的情况下提供援助

- 建立用于可能被转换成化学武器的核查制度

- 在相关领域内和平使用化学的国际合作

受管控的化学物

[编辑]公约区分了三种受管控的化学物,它们可以直接用作化学武器或用于制造化学武器。分类基于商业上生产化学武器的数量。每一类都被分成两部分,A指可以直接用作武器的化学物,B指可以用于制造化学武器的化学物。此外,公约还将毒素定义为:"任何通过化学作用导致人或动物死亡、暂时或永久性损害的化学物,不论它们的来源或生产,以及是否为人工生产。"[21][22][23]

- 一类物质:化学武器以外的用途极少。可以用于研究、医疗、制药、化学武器防御测试等。每年制造100克以上就必须向禁止化学武器组织登记。一个国家被限于最多拥有1吨这些物质。例如,芥子气与神经毒剂。

- 二类物质:有合法的小规模民用。此类物质的制造必须登记,禁止出口给非公约签署国。例如,硫二甘醇用于制造芥子气,也用来作为墨水的溶剂。

- 三类物质:有合法的大规模民用。年产30吨以上的工厂必须登记,允许检查。限制出口给非公约签署国。例如,光气,可以直接作为化学武器,也是许多合法的有机化合物制造的前体;三乙醇胺用于制造芥子气,也用于制造化妆品及洗涤剂。[24]

分类定义

[编辑]化学武器通常被分成三个类别:[25]

- 第一类基于《化学武器公约》附表1的物质;

- 第二类基于非附表1的物质;

- 第三类是设计用来使用化学武器的设备和工具,它们本身不含有这些物质。

成员国

[编辑]在1997年公约生效之前,有165个国家签署了公约,允许其在获得国内批准后批准公约。截至2021年3月,一共有193个缔约国。在四个联合国会员国中,以色列已经签署但并未批准公约,而埃及、朝鲜和南苏丹既没有签署也没有加入公约。安哥拉于2015年9月16日交存加入书,并于同年10月16日生效。[5]台湾虽然不是联合国会员国,但确认遵守公约并于2002年8月27日声明已完全遵守本公约所定的宗旨和原则,倡导禁止发展、生产、储存和使用化学武器,并销毁现有武器。[26][27]

成员国关键组织

[编辑]成员国在禁止化学武器组织(OPCW)中由其常驻代表机构或通常与大使功能相关的国家权威机构代表。为了准备OPCW的视察和制定申报,成员国必须设立国家权威机构。[28]

库存化学武器的销毁

[编辑]全世界一共报告了72304吨化学武器和97个生产设施给禁止化学武器组织。[29]

条约规定的销毁进度

[编辑]条约设立了几个销毁步骤和截止日期,以实现对化学武器的全面销毁,并提供了申请延期的程序。虽然没有国家在条约原始日期之前彻底消除化武,但有几个国家已经在被允许的延长期限下完成了化武销毁工作。[30]

| 阶段 | % 削减 | 截至日期 | 注释 |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 1% | 2000年4月 | |

| II | 20% | 2002年4月 | 完成销毁空的化武弹药、前体物质、添注设备及武器系统 |

| III | 45% | 2004年4月 | |

| IV | 100% | 2007年4月 | 禁止延期超越2012年4月 |

销毁进展

[编辑]截至2019年底,已有70,545吨(占总量的97.51%)的化学制剂通过可查验的方式被销毁。超过57%(497万个)的化学武器和容器也被销毁。[31]

七个国家已经宣布完成化武销毁:阿尔巴尼亚、印度、伊拉克、利比亚、叙利亚、美国以及一个未公开的国家(据称是韩国)。俄罗斯也宣布完成化武库存销毁,但2018年谢尔盖·斯克里帕尔毒杀案,以及2020年阿列克谢·纳瓦利内中毒案,表明俄罗斯可能仍然拥有非法化学武器计划。[32]

2010年10月,中国和日本开始用移动销毁设施销毁第二次世界大战期间日本在中国遗留的化学武器,据报告称已经销毁35,203件(占南京库存的75%)。[33][34]

| 国家 | 加入日期/ 生效日期 |

登记库存 (附表1)(吨) |

%销毁武器(经OPCW核实) (完全销毁日期) |

销毁截止日期 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1997年4月29日 | 17[35] | 100%(2007年7月)[35] | 无 | |

| 1997年4月29日 | 3,000–3,500[36] | 100%(2008年7月)[36] | 无 | |

| 1997年4月29日 | 1,044[37] | 100%(2009年3月)[38] | 无 | |

| 2004年2月5日 | 25[39] | 100%(2014年1月)[39] | 无 | |

| 2013年10月14日[40] | 1,040[41] | 100%(2014年8月)[41] | 无 | |

| 1997年12月5日 | 40,000[42] | 100%(2017年8月)[43] | 无 | |

| 1997年4月29日 | 33,600[44] | 100% (2023年7月) [45] [44] | 2012年4月29日(计划到2023年)[46] | |

| 2009年2月12日 | 残余弹药[47] | 100%(2017年3月)[48] | - | |

| 1997年4月29日 | - | 进行中 | 承诺于2022年[49] |

伊拉克

[编辑]联合国安理会于1991年下令销毁伊拉克的化学武器库存。到1998年,联合国特别委员会检查人员已确认销毁了88,000枚化学武器,包括超过690吨的化学剂,大约4,000吨前体化学品,以及980件关键生产设备。联合国特别委员会检查人员于1998年撤离。[50]

在2009年伊拉克加入公约之前,禁止化学武器组织(OPCW)报告称,自2004年以来,美军已通过露天引爆的方式销毁了大约5000件化学武器。这些化学武器是在1991年海湾战争之前生产的,包括沙林和芥子气。由于缺少维护保养,它们无法像生产初期那样使用。[51][52]

2009年伊拉克加入公约时,它宣称拥有“两个装有和未装满化学武器弹药的设施、一些生产化学武器的前体以及五个旧的化学武器生产设施”。这些设施入口于1994年被1.5米的加强混凝土封闭,这一过程是在联合国特别委员会(UNSCOM)的监督下进行的。截至2012年,销毁化学武器的计划仍在制定中,并且面临着严重困难。2014年,伊斯兰国控制了该设施。[53][54]

2018年3月13日,禁止化学武器组织(OPCW)总干事对伊拉克政府完成了剩余化学武器的销毁工作表示祝贺。[55]

叙利亚

[编辑]2013年叙利亚化学武器袭击事件后,[56]长期被怀疑拥有化学武器的叙利亚政府在2013年9月承认了袭击,并同意将化学武器置于国际监督下。14日,叙利亚向联合国上交了加入《禁止化学武器公约》的文件,并同意其临时有效,2014年10月14日公约正式生效。[57][58][59]一个加速叙利亚化学武器的销毁计划由俄罗斯和美国于14日制定,[60]并得到了联合国安全理事会决议2118[61]和禁止化学武器组织执行委员会决策EC-M-33/DEC.1的支持。化武销毁的截止日期是2014年上半年。[62]叙利亚向OPCW提供了其化学武器库的清单,[63]并于2013年10月开始销毁,是在其正式加入条约之前的两个星期,同时也在申请该公约的临时生效。[64][65]截至2014年8月,所有已申报的类别1材料都已被销毁。然而,2017年汗谢洪化学武器袭击事件表明,该国可能仍拥有未申报的化武库存。2018年杜马化学袭击事件导致至少49名平民死亡,数十人受伤,叙利亚阿萨德政府被指控实施袭击。[66][67][68]

2019年11月,禁止化学武器组织对杜马化学武器袭击的报告引发了争议,维基解密发布了一位OPCW工作人员的电子邮件,其中表示报告“歪曲了事实”并含有“无意中的偏见”。这位工作人员质疑了报告中的一个关键发现,即“有足够的证据来确定,氯气或另一种含氯的反应性气体,很可能是从那些设备中释放出来的”。他声称这个发现“严重地误解了事实并且没有事实支持”,并表示如果这个报告发布,他会附上自己的结果。11月25日,在海牙举行的OPCW年度会议上,总干事费尔南多·阿里亚斯发表演讲,辩护了组织关于杜马事件的报告,称:“尽管一些观点持续在一些公共讨论平台上传播,但我想重申的是,我坚定地支持那项独立、专业的结论。”[69][70]

资助销毁化学武器

[编辑]美国提供了经济援助,以销毁阿尔巴尼亚和利比亚的化学武器。俄罗斯收到了包括美国、英国、德国、荷兰、意大利和加拿大等多个国家的经济支持;至2004年,这些国家已经为俄罗斯提供了大约20亿美元。阿尔巴尼亚销毁化武计划的成本约为4800万美元。美国一共支出200亿美元,并预期将再支出400亿美元。[71]

登记的化学武器生产设施

[编辑]十四个国家已经宣布了其化学武器生产设施(CWPF):[31][72]

目前,已经有97座化武生产设施被停用,并被证实为已销毁(74)或转变为民用(23)。[31]

参见

[编辑]相关国际法

[编辑]- 澳大利亚集团:澳大利亚国家集团和欧盟委员会,帮助成员国确定需要控制的出口,避免化学武器和生物武器的扩散。

- 1990年化学武器协定

- 通用标准:这是国际法中的一个概念,广泛管辖有关化学武器的国际协定。

- 日内瓦议定书:一项禁止缔约国在国际武装冲突中使用化学武器和生物武器的条约

其它类型的大规模杀伤性武器条约

[编辑]化学武器

[编辑]相关纪念日

[编辑]参考文献

[编辑]- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 United Nations Treaty Collection. Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). Accessed 14 January 2009.

- ^ Chemical Weapons Convention, Article 21 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Chemical Weapons Convention, Article 23 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Chemical Weapons Convention, Article 24 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Angola Joins the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. OPCW. [2024-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2024-05-28) (英语).

- ^ 引用错误:没有为名为

:0的参考文献提供内容 - ^ United Nations documents. United Nations. 27 September 2013. p. 1. Retrieved 28 April 2017. Noting that on 14 September 2013, the Syrian Arab Republic deposited with the Secretary-General its instrument of accession to the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction (Convention) and declared that it shall comply with its stipulations and observe them faithfully and sincerely, applying the Convention provisionally pending its entry into force for the Syrian Arab Republic. "Resolution 2118 (2013)". [2024-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2017-07-04).

- ^ "U.S. sanctions Syrian officials for chemical weapons attacks". [2024-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2017-01-17).

- ^ OPCW by the Numbers. OPCW. [2024-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2019-02-02) (英语).

- ^ "Third report of the Organization for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons United Nations Joint Investigative Mechanism". undocs.org. [2024-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2024-10-01).

- ^ 'White phosphorus not used as chemical weapon in Syria'. www.aa.com.tr. [2024-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2023-10-16).

- ^ White phosphorus: weapon on the edge. 2005-11-16 [2024-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2019-11-29) (英国英语).

- ^ UNODA Treaties Database. treaties.unoda.org. [2024-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2024-09-07).

- ^ Feakes, D. The Biological Weapons Convention: -EN- -FR- La Convention sur les armes biologiques -ES- La Convención sobre Armas Biológicas. Revue Scientifique et Technique de l'OIE. 2017-08-01, 36 (2) [2024-05-28]. ISSN 0253-1933. doi:10.20506/rst.36.2.2679. (原始内容存档于2022-03-02).

- ^ The 1993 Chemical Weapons Convention. [2024-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2013-09-28).

- ^ "The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC), opens for signature". [2024-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2022-10-23).

- ^ Herby, Peter. Chemical Weapons Convention enters into force - ICRC. International Review of the Red Cross. 1997-04-30 [2024-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2022-10-22) (美国英语).

- ^ The Intersection of Science and Chemical Disarmament. Beatrice Maneshi and Jonathan E. Forman, Science & Diplomacy, 21 September 2015. [2024-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2017-01-16).

- ^ Syria chemical weapons monitors win Nobel Peace Prize. BBC News. 2013-10-11 [2024-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2024-05-28) (英国英语).

- ^ "Official press release from Nobel prize Committee". Nobel Prize Organization. 11 October 2013. Retrieved 11 October 2013. [2024-05-28]. (原始内容存档于2024-10-07) (美国英语).

- ^ "Monitoring Chemicals with Possible Chemical Weapons Applications" (PDF). Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. 7 December 2014. Fact sheet 7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 18 March 2018. [2024-06-04]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2017-07-14).

- ^ Annex on Chemicals. OPCW. [2024-06-04]. (原始内容存档于2024-03-06) (英语).

- ^ Article II – Definitions and Criteria. Chemical Weapons Convention. Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. Retrieved 7 September 2013. [2024-06-04]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-25) (英语).

- ^ CDC | Facts About Phosgene. emergency.cdc.gov. 2023-08-31 [2024-06-04]. (原始内容存档于2023-05-15) (美国英语).

- ^ The Chemical Weapons Convention (CWC) at a Glance | Arms Control Association. www.armscontrol.org. [2024-06-04]. (原始内容存档于2024-07-09).

- ^ China Chemical Chronology (PDF). 美国华盛顿特区: Nuclear Threat Initiative. 2012-06 [2023-10-06]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2024-09-26) (英语).

- ^ Taiwan Overview. 美国华盛顿特区: James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies, Middlebury Institute of International Studies. 2023-09-06 [2024-09-14]. (原始内容存档于2023-09-29) –通过Nuclear Threat Initiative (英语).

- ^ Chemical Weapons Convention. OPCW. [2024-06-04]. (原始内容存档于2024-07-19) (英语).

- ^ OPCW by the Numbers. OPCW. [2024-06-04]. (原始内容存档于2019-02-02) (英语).

- ^ Willaims, Sophie. Russia destroys ALL chemical weapons and calls on USA to do the same. Express.co.uk. 2017-09-27 [2024-06-04] (英语).

- ^ 31.0 31.1 31.2 OPCW chief announces destruction of over 96% of chemical weapons in the world. TASS. [2024-06-04]. (原始内容存档于2024-08-17).

- ^ Syria, Russia, and the Global Chemical Weapons Crisis | Arms Control Association. www.armscontrol.org. [2024-06-04]. (原始内容存档于2024-07-18).

- ^ "Opening Statement by the Director-General to the Conference of the States Parties at its Sixteenth Session" (PDF). OPCW. 28 November 2011. Retrieved 1 May 2012. [2024-06-04]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-02-13).

- ^ Executive Council 61, Decision 1 (PDF). OPCW. 2010. [2024-06-04]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-02-13).

- ^ 35.0 35.1 Albania the First Country to Destroy All Its Chemical Weapons. OPCW. 2007-07-12 [2015-05-15]. (原始内容存档于2015-09-18).

- ^ 36.0 36.1 Schneidmiller, Chris. South Korea Completes Chemical Weapons Disposal. Nuclear Threat Initiative. 2008-10-17 [2015-05-15]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-11).

- ^ India Country Profile – Chemical. Nuclear Threat Initiative. February 2015 [2015-05-15]. (原始内容存档于2015-04-04).

- ^ Schneidmiller, Chris. India Completes Chemical Weapons Disposal; Iraq Declares Stockpile. Nuclear Threat Initiative. 2009-04-27 [2015-05-15]. (原始内容存档于2015-06-10).

- ^ 39.0 39.1 Libya Completes Destruction of Its Category 1 Chemical Weapons. OPCW. 2014-02-04 [2018-04-16]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-05).

- ^ Syria applied the convention provisionally from 14 September 2013

- ^ 41.0 41.1 OPCW: All Category 1 Chemicals Declared by Syria Now Destroyed. OPCW. 2014-08-28 [2015-05-14]. (原始内容存档于2018-04-22).

- ^ Chemical Weapons Destruction. Government of Canada – Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada. 2012-10-16 [2015-05-15]. (原始内容存档于2015-05-18).

- ^ OPCW Director-General Commends Major Milestone as Russia Completes Destruction of Chemical Weapons Stockpile under OPCW Verification. OPCW. 2017-09-27 [2017-09-28]. (原始内容存档于2018-09-02).

- ^ 44.0 44.1 Contreras, Evelio. U.S. to begin destroying its stockpile of chemical weapons in Pueblo, Colorado. CNN. 2015-03-17 [2015-05-15]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-11).

- ^ OPCW confirms: All declared chemical weapons stockpiles verified as irreversibly destroyed. OPCW. [2023-07-10]. (原始内容存档于2023-09-13) (英语).

- ^ Hughes, Trevor. 780,000 chemical weapons being destroyed in Colo.. USA TODAY. 2015-04-25 [2015-05-15]. (原始内容存档于2021-03-11).

- ^ Progress report on the preparation of the destruction plan for the al Muthanna bunkers (PDF). OPCW. 1 May 2012 [16 May 2015]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-05-28).

- ^ 存档副本. [2018-04-16]. (原始内容存档于2018-03-27).

- ^ 存档副本 (PDF). [2018-04-16]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-04-18).

- ^ Iraq | Country Profiles | NTI. web.archive.org. 2015-02-07 [2024-06-05]. 原始内容存档于2015-02-07.

- ^ Chivers, C. J. Thousands of Iraq Chemical Weapons Destroyed in Open Air, Watchdog Says. The New York Times. 2014-11-22 [2024-06-05]. ISSN 0362-4331. (原始内容存档于2022-10-11) (美国英语).

- ^ Shrader, Katherine (22 June 2006). "New Intel Report Reignites Iraq Arms Fight". The Washington Post. Associated Press. Retrieved 16 May 2015. [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档于2017-03-30).

- ^ Iraq Faces Major Challenges in Destroying Its Legacy Chemical Weapons | James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS). web.archive.org. 2010-03-29 [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档于2010-03-29).

- ^ Press, Associated. Isis seizes former chemical weapons plant in Iraq. The Guardian. 2014-07-09 [2024-06-05]. ISSN 0261-3077. (原始内容存档于2023-08-30) (英国英语).

- ^ OPCW Director-General Congratulates Iraq on Complete Destruction of Chemical Weapons Remnants. OPCW. [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档于2024-06-05) (英语).

- ^ Borger, Julian; Wintour, Patrick. Russia calls on Syria to hand over chemical weapons. The Guardian. 2013-09-09 [2024-06-05]. ISSN 0261-3077. (原始内容存档于2018-10-23) (英国英语).

- ^ Barnard, Anne. In Shift, Syrian Official Admits Government Has Chemical Arms. The New York Times. 2013-09-11 [2024-06-05]. ISSN 0362-4331. (原始内容存档于2023-06-29) (美国英语).

- ^ "Depositary Norification" (PDF). [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2013-09-21).

- ^ "Secretary-General Receives Letter from Syrian Government Informing Him President Has Signed Legislative Decree for Accession to Chemical Weapons Convention". United Nations. 12 September 2013. [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档于2014-02-20).

- ^ Gordon, Michael R. U.S. and Russia Reach Deal to Destroy Syria’s Chemical Arms. The New York Times. 2013-09-14 [2024-06-05]. ISSN 0362-4331. (原始内容存档于2013-09-14) (美国英语).

- ^ Syrian Chemical Arms Inspections Could Begin Soon | TIME.com. web.archive.org. 2013-10-20 [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档于2013-10-20).

- ^ "Decision: Destruction of Syrian Chemical Weapons" (PDF). OPCW. 27 September 2013. Retrieved 28 September 2013. [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2017-03-26).

- ^ Syria chemical arms removal begins. BBC News. 2013-10-06 [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档于2024-08-17) (英国英语).

- ^ World News: Latest International Headlines, Video, and Breaking Stories From Around The Globe. NBC News. [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档于2018-11-03) (英语).

- ^ Mariam Karouny (6 October 2013). "Destruction of Syrian chemical weapons begins: mission". Reuters. Archived from the original on 7 October 2013. Retrieved 8 October 2013. [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档于2013-10-07).

- ^ Gaouette, Nicole. Haley says Russia’s hands are ‘covered in the blood of Syrian children’ | CNN Politics. CNN. 2018-04-09 [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档于2024-09-03) (英语).

- ^ Syria war: At least 70 killed in suspected chemical attack in Douma. BBC News. 2018-04-08 [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档于2018-04-12) (英国英语).

- ^ OPCW confirms chemical attack in Syria – DW – 03/01/2019. dw.com. [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档于2024-06-30) (英语).

- ^ Norman, Greg. Syria watchdog accused of making misleading edits in report on chemical weapons attack. Fox News. 2019-11-25 [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档于2024-06-05) (美国英语).

- ^ Chemical weapons watchdog OPCW defends Douma chlorine gas attack report as WikiLeaks, Russia and Syria claim bias today - CBS News. www.cbsnews.com. 2019-11-25 [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档于2020-02-14) (美国英语).

- ^ Russia, U.S. face challenge on chemical weapons. Stephanie Nebehay, Reuters, 7 August 2007, accessed 7 August 2007. [2024-06-05]. (原始内容存档于2022-04-14).

- ^ "Eliminating Chemical Weapons and Chemical Weapons Production Facilities" (PDF). Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons. November 2017. [2024-06-04]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2018-10-12).

- ^ McLaughlin, Jessica. Confidentiality and verification: the IAEA and OPCW (PDF). Trust & Verify. No. 114 (英国伦敦: Verification Research, Training and Information Centre). 2004-06-05: 3 [2024-06-03]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-05-20) (英语).

外部链接

[编辑]- 中华民国经济部工业局禁止化学武器公约推广资讯网

- Chemical Weapons Convention Website, United States

- Chemical Weapons Convention Website, Singapore

- Chemical Weapons Convention: Full Text (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Chemical Weapons Convention: Ratifying Countries (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Annex on Chemicals, describing the schedules and the substances on them, OPCW website

- The Chemical Weapons Convention at a Glance (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), Arms Control Association

- Chemical Warfare Chemicals and Precursors (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), Chemlink Pty Ltd, Australia

- Introductory note by Michael Bothe, procedural history note and audiovisual material (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) on the Convention on the Prohibition of the Development, Production, Stockpiling and Use of Chemical Weapons and on their Destruction in the Historic Archives of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Lecture (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) by Santiago Oñate Laborde entiteld The Chemical Weapons Convention: an Overview in the Lecture Series of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)